BEFORE THE ilLINOIS POLLUTION CONTROL BOARD

FOX MORAINE, LLC,

Petitioner,

v.

UNITED CITY OF YORKVILLE, CITY

COUNCIL,

Respondent.

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

PCB No. PCB 07-146

NOTICE OF FILING

TO:

All counsel ofRecord (see attached Service List)

Please take notice that on August 30, 2007, the undersigned filed

with

the Illinois

Pollution Control Board, 100 West Randolph Street, Chicago, lllinois 60601,

the Petitioner's

Response to the Motion for Protective Order Limiting Discovery.

Dated:

August 30, 2007

Charles

F. Helsten

Hinshaw

&

Culbertson LLP

100 Park Avenue

P.O. Box 1389

Rockford, IL 61105-1389

815-490-4900

Respectfully submitted,

On

behalf of FOX MORAINE, LLC

lsi

Charles F. Helsten

One

ofIts Attorneys

This document utilized 100% recycled paper products.

10S3S423v! 863858

Electronic Filing, Received, Clerk's Office, August 30, 2007

BEFORE THE ILLINOIS POLLUTION CONTROL BOARD

Fox Moraine, L.L.C.,

Petitioner,

v.

United city ofYorkville, City Council,

Respondents.

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

PCB No. PCB No. 07-146

PETITIONER'S RESPONSE TO THE MOTION FOR

PROTECTIVE

ORDER LIMITING DISCOVERY

NOW COMES the Petitioner, FOX MORAINE, L.L.C., by and through its attorneys,

Charles F. Helsten and George Mueller, and in response to the Motion for a Protective Order

Limiting Discovery, states as follows:

INTRODUCTION

The gist of the City's Motion for Protective Order Limiting Discovery is that the

Petitioner did not preserve its right to challenge the fundamental fairness violations in the

proceedings below, and is therefore barred from discovering evidence

of those violations and

revealing that evidence in this appeal before the Board. The City's assertion is not only patently

false, it ignores this Board's Rules concerning discovery and is an affront to the very principles

of fundamental fairness.

The Petitioner, Fox Moraine, raised fundamental fairness concerns from the onset

of the

public hearing for siting approval, on March 7, 2007. (petition for Review, Exhibits B and C).

At the commencement of the hearing, the Petitioner filed a Motion to Disqualify in which it

delineated the bias demonstrated by two members of the Council based on their pre-hearing

expressions ofpublic opposition to the Application, their solicitation of legal advice for purposes

of opposing the Application, and a variety of other disqualifying conflicts of interest.

ld.

After

the close

of the siting hearing, when the rules prevented Fox Moraine from making any further

70535372vl 863858

comments or presentations, three newly elected Council members were seated; the timing of

their arrival then leaving the Petitioner unable to take any action to disqualify them.

Despite the recommendation

of its own independent review staffand the Hearing Officer,

the City Council denied the siting Application, and, in the aftermath of that decision, the

Petitioner appealed to this Board on the basis of multiple fundamental fairness violations and on

the basis that the decision was against the manifest weight of the evidence at the hearing.

In conjunction with its appeal to this Board, the Petitioner propounded discovery

consistent with 35 Ill.Adm.Code 101.616. That section provides that "[a]11 relevant information

and information calculated to lead to relevant information is discoverable, excluding those

materials that would be protected from disclosure in the courts of this State pursuant to statute,

Supreme Court Rules or common law, and materials protected from disclosure under 35 Ill.

Adm. Code

130." 35 Ill.Adm.Code 101.616(a).

The Petitioner's Interrogatories seek disclosure

of evidence that establishes bias,

ex parte

contacts, prejudgment and a decision based on matters outside the public record, all legitimate

areas

of inquiry as established by the case law in this area. The City has been asked to disclose

the

ex parte

communications; the gifts andlor transfers between Council members and the

Participant/Objectors; the Council members' affiliations with the Objector organizations; and the

materials and information outside the record of proceedings which were considered by the

Council in reaching its decision.

The Petitioner's Requests for Production simply seek

production

of the documentary evidence of these violations. The discovery propounded in this

case is narrowly tailored to result in disclosure of the evidence establishing violations of

fundamental fairness which lie at the heart ofthe instant Appeal.

Upon receiving the Petitioner's requests for disclosures

of evidence, the City responded

with a Motion for Protective Order in which it asserted that it did not need to produce the

2

70535372vl 863858

evidence because the Petitioner purportedly "waived the issues on which it seeks discovery."

In

support of this assertion, the City pointed to the fact that Motions to Disqualify were only filed

against two members

of the siting authority. (Motion for Protective Order at p. 2). However,

and again, the City'smotion completely ignores the fact that the Petitioner also seeks evidence of

ex parte

contacts, as well as evidence of the Council's consideration of materials outside the

record in reaching its decision, and similarly ignores the timing

of the post-hearing seating of

three members ofthe Council.

The City's assertion that the Petitioner "waived its right" to discover evidence

of the

fundamental fairness violations is not only

in contravention with the Board's rules providing for

discovery, it also seeks to deny the Board access to vital evidence. This attempt to withhold

evidence suggests the City

may be well aware of the fundamental fairness violations which

occurred in the proceedings below, and is doing everything possible

to prevent such conduct

from seeing the light

of objective scrutiny.

ARGUMENT

1.

The Board's Procedural Rules Concerning Discovery

Under the Board's Procedural Rules, "[a]l1 relevant infonnation and information

calculated to lead to relevant information is discoverable, excluding those materials that would

be protected from disclosure

in

the courts of this State pursuant to statute, Supreme Court Rules

or common law, and materials protected from disclosure under 35 Ill. Adm. Code 130." Sec.

101.616(a).

The Rules provide that a protective order is available solely ''toprevent unreasonable

expense, or harassment, to expedite resolution

of the proceeding, or to protect non-disclosable

materials from disclosure consistent with Sections 7 and

7.1 of the Act and 35 Ill.Adm.Code

130." Sec. 101.616(d). No such basis for a Protective Order has been raised by the City, and

3

70535372vl 863858

indeed, the discovery requested by the Petitioner falls into none of the above-referenced

categories. Rather, the discovery here seeks only production

of evidence showing fundamental

fairness violations, including a request for disclosure

of

ex parte

contacts, any inappropriate

relationships between the Council members and Objector Participants, and materials

or

infonnation outside the record which were considered by the Council in reaching its decision.

For purposes

of Discovery, "the Board may look

to

the Code of Civil Procedure and the

Supreme Court Rules for guidance where the Board'sprocedural roles are silent." Sec. 101.616.

In

describing the scope of discovery, Supreme Court Rule 201 (b)(1) states that "full disclosure

regarding any matter relevant to the subject matter involved in the pending action" can

be had.

Although the City points

to

Joliet Sand and Gravel

v.

PCB,

163 1ll.App.3d 830, 516

N.E.2d 955

(3

rd

Dist. 1987) as authority for the Board to deny discovery, in that case the

petitioner sought to "depose, subpoena

or both no less than 19 people. Many of these persons

had no direct bearing

on the denial of the operating pennit."

ld.

at 835. The Appellate Court

accordingly upheld the hearing officer's decision to limit the number

of testifying witnesses

to

five, and declined to require production of memoranda which had been created by IEPA

personnel and attorneys with respect to a decision

on whether to bring an action against an

alleged polluter.

ld.

The discovery limitations imposed in

Joliet Sand and Gravel

clearly have

no relevance to the instant case, where the Petitioner has submitted narrowly tailored requests

which go directly to the issues raised in this appeal.

The other case relied upon

by the City in its argwnent for limiting discovery,

Snoddy

v.

Teepak,

198 IlI.App.3d 966,556 N.E.2d 682 (1

st

Dist. 1990), is a battery case far afield from the

matters before this Board, in which a worker sued his employer and the manufacturer

of

chemicals used at his employer's facility. The case is so dissimilar, and so utterly bereft of

factual detail, that its applicability to the instant case is nearly impossible to discern. Its only

4

70535372vl 863858

relevance derives from the fact that the Appellate Court held the trial court properly declined to

compel discovery which was

"not calculated to develop specific probative evidence regarding

the issue

of fraud, collusion, or tortious conduct."

Id.

at 969. Unfortunately, the opinion offers

no indication as to what kind

of evidence the plaintiff did seek, or on what subjects. In any

event, the Appellate Court found that the trial court correctly held that the requested discovery

was unnecessary since the case could

be decided without an evidentiary hearing. Moreover, the

fact that there exists a case in which the Appellate Court once found that

it was appropriate to

limit discovery hardly supports the City's motion here. Finally, in contrast with

Snoddy,

the

discovery in this case is focused directly at the issues

on appeal.

2.

Discovery in the Context of Fundamental Fairness

In

the instant appeal, the Petitioner clearly raised fundamental fairness as an issue during

the proceedings below, and raised the issue again in its Petition for Review. Indeed, fundamental

fairness is the very core

of this appeal. Thus it is clear that discovery intended to reveal

infonnation and documents evidencing the fundamental fairness violations that occurred below

is tailored to matters entirely relevant to the instant appeal.

Because a Section 39.2 hearing must

be fundamentally fair to all participants, and must

be heard by a siting authority which is objective and unbiased, the Board has a

statutory duty

to

consider the fundamental fairness

ofthe siting process. 415 ILCS

5/40.1

(2002);

E

&

E Hauling,

Inc.

v.

Pollution Control Bd.,

116 Ill.App.3d 586, 596, 451 N.E.2d 555, 564 (2d Dist. 1983);

aff'd,

107 Ill.2d 33, 481 N.E.2d 664 (1985). "The Act provides that, in reviewing a section 39.2

decision

on site approval, the Board

must

consider the fundamental fairness of the procedures

used

by the local governing body in reaching its decision."

Land and Lakes

v.

PCB, 245

Ill.App.3d 631, 616 N.E.2d 349 (300 Dist. 1993) (emphasis added) (reversing the Pollution

Control Board'sdecision, based on a lack

of fundamental fairness in proceedings below).

5

70535372vl 863858

It is well-settled that although the Act requires that Board hearings on siting decisions be

based exclusively on the record before the siting authority, the Board may consider new evidence

relevant to the fundamental fairness

of those proceedings "where such evidence necessarily lies

outside of the record."

Land and Lakes Co.

v.

PCB,

31911LApp. 3d 41, 743 N.E.2d 188, 194 (3rd

Dist. 2000) (emphasis added). Such a situation is present in this case, and is often true when it

comes to fundamental fairness violations.

Fundamental fairness involves considerations

of bias, prejudgment, decisions based on

matters outside the record, and

ex parte

contacts. The discovery requests to which the City has

so strenuously objected merely ask that the City provide any evidence in its possession which

establishes such bias, prejudgment, consideration

of matters outside the record, and

ex parte

contacts (again, all well-established areas of fundamental fairness inquiry).

It

is axiomatic that no person may playa decision-making role

In

a judicial or

administrative proceeding

in

which he or she has any personal or pecuniary interest in the

outcome which might influence his or her decision.

See e.g., Board ofEduc. ofNiles Tp. High

School Dist.

219,

Cook Co.

v.

Regional Bd. ofSchool Trustees ofCook Co.,

127 Ill.App.3d 210,

213 (1st Dist.1984). Participation

by such interested parties

in

the decision making process is

said to "infect the whole" and render the decision voidable.

ld.

Here, multiple members of the Council had a personal interest in the outcome, and

engaged in a variety

of improper acts and conduct with respect to the Application, yet the City

asserts it should be completely insulated from disclosing the evidence related to that conduct and

establishing those conflicts because the Petitioner didn't discover much

of it until the hearings

were over. That assertion is at total odds with the law.

3.

Waiver

6

70535372vl 8638.58

The City asserts that the Petitioner ''waived''its right to seek disclosure of the evidence of

fundamental fairness violations because it only filed a motion to disqualify two of the siting

authority members. 1 In support

of its argument, the City cites to

E

&

E Hauling

v.

PCB

for the

proposition that it is improper for a party to raise a claim

of bias for the first time on appeal.

(City's Motion at p.3).

In

the instant case, of course, bias was, in fact, raised as an issue in the

proceedings below, therefore bias is not being raised as an issue for the first time on appeal.

Moreover, the City's argument and citation to

E

&

E

Hauling

fails to acknowledge that in that

case the Illinois Supreme Court observed the exceptions to the waiver rule, and went on to

address the petitioner's claims

of bias in great depth, despite the fact that they were apparently

not raised

in the proceedings below.

E

&

E Hauling

v.

PCB,

107 Il1.2d 33,38-9 (1985). It is also

worth noting that in

E

&

E Hauling,

the Supreme Court affirmed the Appellate Court, which had

explained that the waiver rule is "not inflexible and may encompass challenges to the

composition

of administrative bodies made for the first time on administrative review wherein

injustice might otherwise result."

E

&

E

Hauling

v.

PCB,

116 I11.App.3d 586, 593, 451 NE2d

555 (2

nd

Dist. 1993),

ajJ'd

107 1ll.2d 33, 481 N.E.2d 664 (1985). The City points to

Waste

Management

v.

PCB,

175 Ill.Appp.3d 1023, 530 N.E.2d 682 (2

nd

Dist. 1988) as allegedly

providing additional support for its waiver theory, yet the petitioner in that case failed to seek

disqualification ofsiting authority members despite the fact that it knew they had publicly voiced

opposition to the landfill, and instead urged disqualification

of them only on appeal. The instant

case is easily distinguishable, since the Petitioner here promptly moved to disqualify those

members who publicly opposed the Application, and now appeals concerning additional bias

which was unknown at the time

ofthe hearing.

1 Notably, the City relies exclusively

on cases that are in excess of fifteen years old to support its

waiver theory, thereby ignoring the Board's clear duty to consider fundamental fairness issues,

as is clearly reflected in more recent cases addressing the subject.

7

70535372vl 863858

The City's reliance on

A.R.R Landfill v. PCB,

174 m.App.3d 82, 528 N.E.2d. 390 (2

nd

Dist. 1988), is similarly misplaced. The City asserts that

in

A.R.F

the Appellate Court found a

landfill waived claims

of bias when it withheld those claims until its appeal of

an

unfavorable

decision. (City's Memorandum

of Law at p. 3).

In

A.R.R,

however, the petitioner had been

allowed to submit written questions to the members

of the siting authority prior to the hearing, in

which the members were asked

to - and did - disclose their public statements critical of the

landfill. Nevertheless, the petitioner failed to seek disqualification based

on the statements

received from members until after the siting decision was announced, raising its

claims of bias

for the first time

on appeal. The Appellate Court held in

A.R.F

that the petitioner in that case had

a duty to raise the claim promptly after it obtained knowledge of the alleged disqualification.

Id.

at 88. This is clearly distinguishable from the facts present in the instant appeal.

Here, waiver is inapplicable because the information was unknown at the time

of the

hearing. A waiver is the voluntary relinquishment

of a known right, and the Petitioner cannot be

deemed to have waived its objection to individuals who were not even seated as members of the

Council until after the hearing, when it was too late for the Petitioner to move for their

disqualification to disqualify them. Even the City acknowledges that a "claim

of bias or

prejudice on the part of a member of

an

administrative agency...must be asserted promptly after

knowledge

of the alleged disqualification." (City's Memorandum of Law at p. 3, citing

Waste

Management v. PCB,

175 Ill.App.3d 1023 (2

nd

Dist. 1988)(emphasis added). Here, knowledge

ofthe additional disqualifications did not occur until after the hearing had concluded.

Similarly, the Petitioner could not possibly "waive" its right to discover materials outside

the record which were considered

by the Council in reaching its decision by failing to raise an

objection during

the hearing to something which had not yet occurred or which was not yet

known.

8

7053 5372v I 863858

Fox Moraine had reason to believe at the outset of the hearings that two Council

members were tainted, and properly moved to disqualify them. Fox Moraine did not and could

not know at the time that the entire process was tainted, however, a decision which shockingly

ignored the strong recommendations for approval by both the Hearing Officer and the City'sown

independent review staff makes no other conclusion possible.

It

is the very nature of

ex parte

contracts that they are furtive, and it is the essence of bias that it is hidden from those against

whom it will be directed. That is why the Board has a statutory obligation to examine the

fundamental fairness of a proceeding. No action on the part of Fox Moraine was required during

the hearing to preserve this issue beyond what was done.

The fact that Council members participated

in heretofore undisclosed

ex parte

contacts,

based their final decision on previously undisclosed materials, communications, and other

infonnation outside the record, and in other ways prejudged the Application and disregarded the

evidence at the hearing, does not justify a determination that the hearing was fundamentally fair,

and the Board

has

a statutory responsibility to determine whether, in fact, the hearing process in

this case met the standards of fundamental fairness.

If the City has no infonnation or materials that would substantiate the violations, it has

nothing

to

fear

in

answering the Petitioner's discovery requests. It is the alternative to that

proposition which should raise concern for this Board, and most likely explains why the City has

so strenuously objected to an otherwise routine discovery request in fundamental fairness cases.

CONCLUSION

It has been said that the very essence of constitutional due process is based on the concept

of fundamental fairness, and TIlinois courts have consistently held that at a minimum,

fundamental fairness requires a fair hearing before a fair tribunal.

See e.g. Van Harken v. City of

Chicago,

305 m.App.3d 972 (1st Dist. 1999).

9

70535372vl 863858

As the Appellate court

has

observed, shielding off-record considerations from judicial

review not only frustrates the pwpose of review by preventing consideration of fundamental

fairness issues, it also visits unjust results on parties who have been "actually victimized by

unfair or improper procedures not of record,"

E

&

E Hauling, Inc. v.

PCB,

116 m.App.3d 586,

593, 451 N.E.2d 555, 562 (2

nd

Dist. 1983),

aff'd.,

107 n1.2d 33, 481 N.E.2d 664 (1985). That

type of victimization occurred in this case, and the Petitioner should be afforded access to the

evidence which reveals the extent ofthe violations that occurred in the proceedings below.

The City's Motion for Protective Order seeks to obfuscate this Board's inquiry into the

fundamental fairness of the proceedings below, and to prevent consideration of relevant

evidence. The Petitioner accordingly requests that it be denied.

Dated:

August 30, 2007

Charles F. Helsten

Hinshaw

&

Culbertson LLP

100 Park Avenue

P.O. Box 1389

Rockford,

IL

61105-1389

815-490-4900

George Mueller

Mueller Anderson, P.c.

609 Etna Road

Ottawa, TIlinois 61350

815-431-1500

Respectfully submitted,

On behalf of Fox Moraine, LLC

lsi

Charles F. Helsten

and

lsi

George Mueller

This document utilized 1

O~~

recycled paper products.

70535372vl 863858

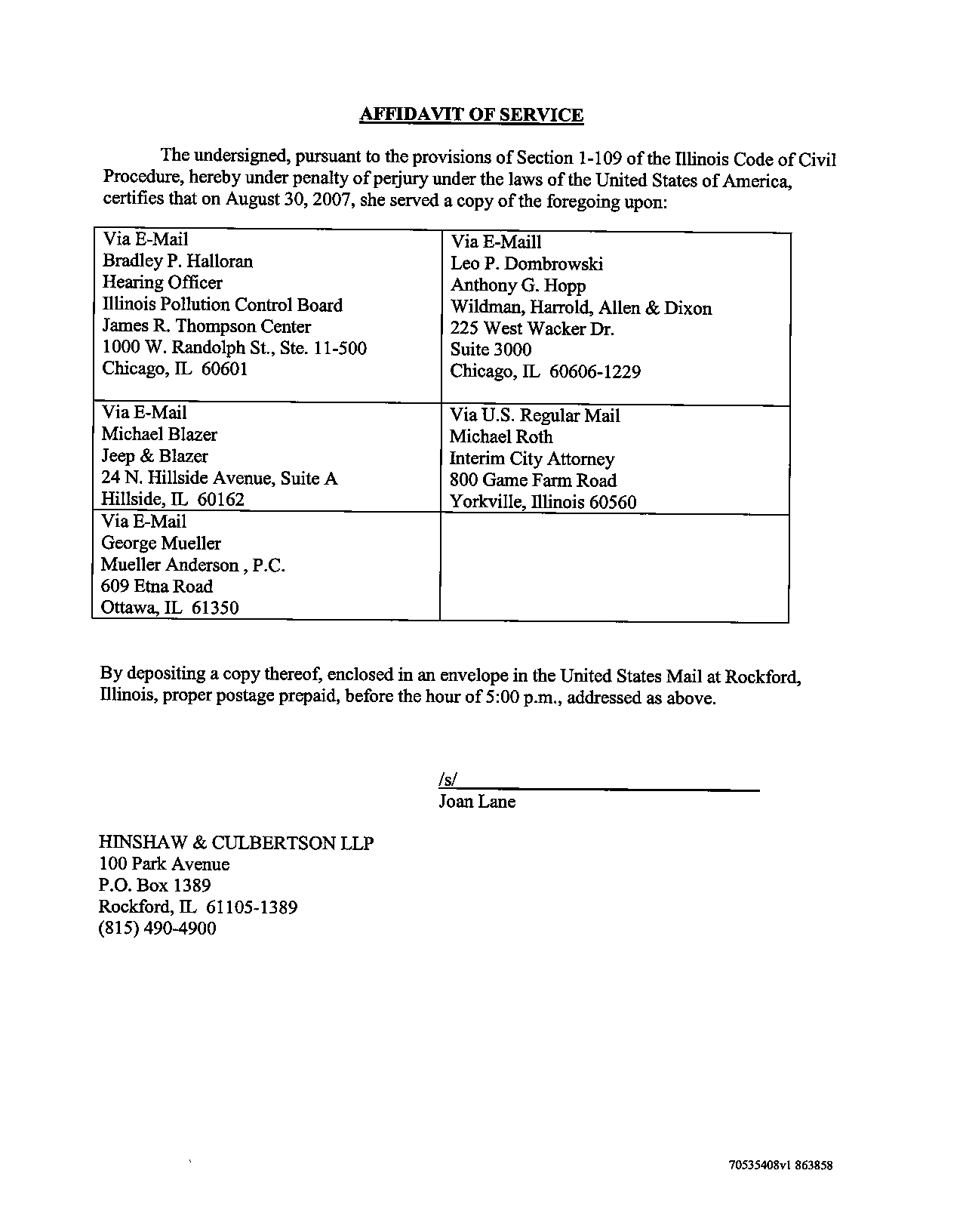

AFFIDAVIT OF SERVICE

The undersigned, pursuant to the provisions of Section 1-109 of the nlinois Code of Civil

Procedure, hereby under penalty

ofperjury under the laws of the United States of America,

certifies that on August

30, 2007, she served a copy ofthe foregoing upon:

Via E-Mail

ViaE-Main

Bradley P. Halloran

Leo

P. Dombrowski

Hearing Officer

Anthony

G. Hopp

Illinois Pollution Control Board

Wildman, Harrold, Allen

&

Dixon

James

R

Thompson Center

225 West Wacker Dr.

1000 W. Randolph St., Ste. 11-500

Suite 3000

Chicago, IL 60601

Chicago,IL 60606-1229

ViaE-Mail

Via U.S. Regular Mail

Michael Blazer

Michael Roth

Jeep

&

Blazer

Interim City Attorney

24

N. Hillside Avenue, Suite A

800 Game Fann Road

Hillside, IL 60162

Yorkville, lllinois 60560

ViaE-Mail

George Mueller

Mueller

Anderson, P.C.

609 Etna Road

Ottawa,

IL 61350

By depositing a copy thereof, enclosed in an envelope in the United States Mail at Rockford,

Dlinois, proper postage prepaid, before the

hour of 5:00 p.m., addressed as above.

lsi

Joan Lane

HINSHAW

&

CULBERTSON LLP

100

Park Avenue

P.O.

Box 1389

Rockford, IL 61105-1389

(815) 490-4900

70535408vl 863858