BEFORE THE ILLINOIS POLLUTION CONTROL BOARD

IN THE MATTER OF:

)

)

PROPOSED AMENDMENTS TO:

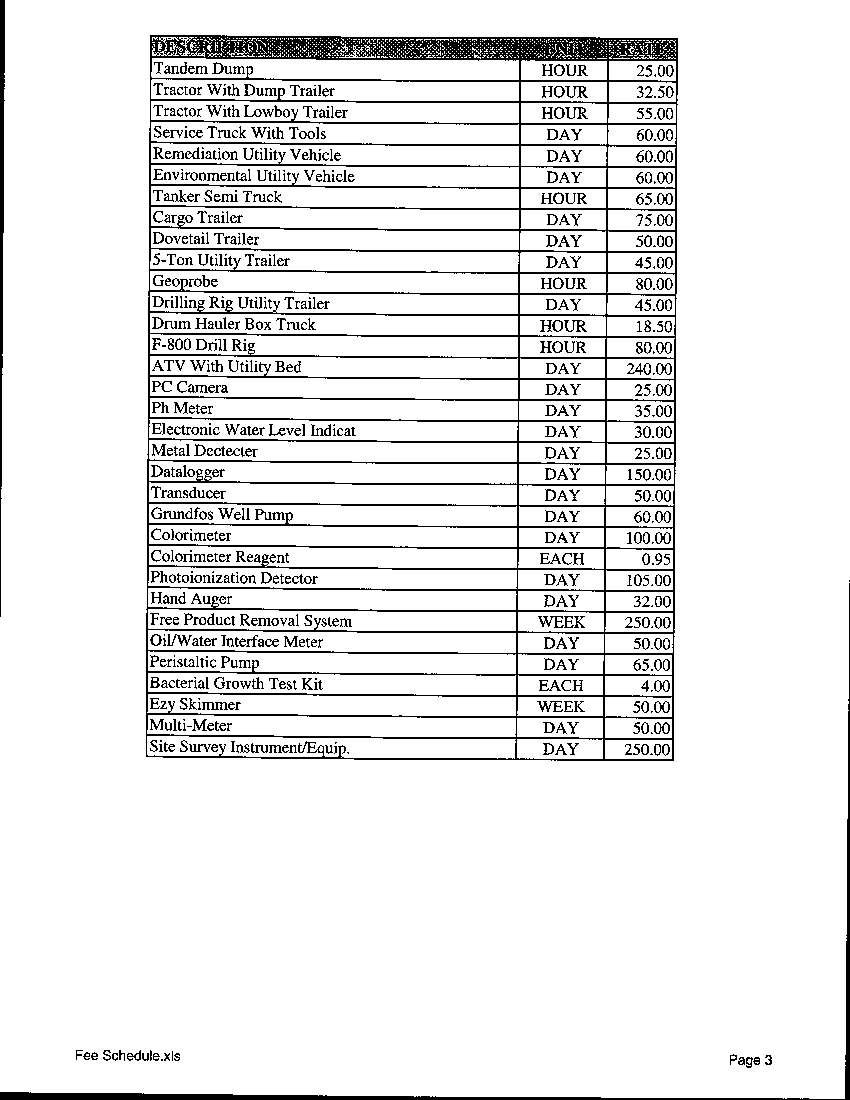

)

R04-022

REGULATION OF PETROLEUM

)

(UST Rulemaking)

LEAKING UNDERGROUND STORAGE )

TANKS (35 ILL.ADM.CODE 732)

)

)

IN THE MATTER OF:

)

)

PROPOSED AMENDMENTS TO:

)

R04-023

REGULATION OF PETROLEUM

)

(UST Rulemaking)

LEAKING UNDERGROUND STORAGE )

Consolidated

TANKS (35 ILL.ADM.CODE 734)

)

TESTIMONY OF UNITED SCIENCE INDUSTRIES, INC. TO ALTER THE ILLINOIS

ENVIRONMENTAL PROECTION AGENCY’S PROPOSAL TO AMEND 35 ILL.

ADM. CODE 732 AND 35 ILL. ADM. CODE 734

My name is Jay P Koch. I am President & CEO of United Science Industries,

Inc. (USI) located in, Woodlawn, Illinois. In one means or another I have been involved

with the Illinois Leaking Underground Storage Tank (LUST) Program since founding

USI in the fall of 1989.

Like many individuals that have been affiliated with the Illinois LUST program

since its formative days, I have witnessed the trials, tribulations and triumphs of its

evolution. Over the course of the past fifteen years, the LUST program has endured at

least two funding crises and several legislative and regulatory changes. Nearly every

crisis and legislative/regulatory change has been memorable. Countless companies have

entered and left this industry for a variety of reasons, but those that are truly dedicated to

this industry and their mission always seem to endure. We are experienced, strong, well

managed, adaptive and dedicated to this industry and to our mission.

Page 1 of 49

ELECTRONIC FILING, RECEIVED, CLERK'S OFFICE JULY 8, 2005

I am here today not only on behalf of United Science Industries, Inc., our

employees and our clients but also to speak for a class of underground storage tank

owner/operator that, to my knowledge, has been absent from these proceedings to this

point. This class of owner/operator typically consists of the small business person, the

retiree, the estate, the widow, the school district, the church, the agricultural cooperative,

etc. that has from one to two incidents to remediate. These owners/operators are not

large corporations or wealthy endowments. They are everyday law-abiding citizens and

small businesses. They are our neighbors, our friends and our clients and they live in

communities from Cairo to Chicago, from the Indiana state line to the Mississippi River.

In fact, as a group, they comprise the ownership of approximately 88% of all

owner/operators of all leaking underground storage tank sites in the State. They also

represent nearly 62.4 percent of the incidents that remain to be remediated. These

citizens and small businesses are typically not well capitalized and they are not well

represented. Unlike the major oil companies, large petroleum distributors and

convenience store chains that are represented by groups such as the Illinois Petroleum

Council, the Illinois Petroleum Marketer’s Association/Illinois Association of

Convenience Stores and the Illinois State Chamber of Commerce, I am not aware of a

single trade organization or special interest group that serves the collective interest of this

class of owner/operator. These owners/operators are the “silent majority”. And, as I

have stated previously, I am not aware that anyone has testified on behalf of these

owner’s/operators during the proceedings in this rulemaking. USI is well versed in the

needs of this class of underground storage tank owners/operators. In fact, USI’s in-house

marketing statistics and the statistics published on the Illinois Environmental Protection

Page 2 of 49

Agency’s web site both indicate that United Science Industries, Inc. serves more of this

class of underground storage owner/operator than any other environmental consultant in

the State of Illinois. I, and several of the employees of United Science Industries, Inc.,

am here today not only to represent our organization, but to also speak to the needs of the

“silent majority”; the needs of the thousands of owners/operators that have one or two

incidents that they must remediate (hereinafter referred to as the “small owner/operator”).

The small owner/operator has a number of special needs, but most immediately

they need three things:

First, they need the record in this proceeding to be set straight.

Secondly, they need you, the Illinois Pollution Control Board, to listen closely

today. They need you to listen to testimony that will question the IEPA’s stated motives

in this rulemaking. They need you to listen to the numerous conceptual flaws that make

key portions of the currently proposed rule un-workable and intolerable. They need you

to listen to testimony that will show that the Illinois EPA has over-stepped its scope of

administrative authority in proposing certain key portions of the proposed rule that are

contrary to the legislative intent of the Public Acts that define public policy on matters

that are at the heart of this rule. They need you to listen; not to the speculation,

conjecture, and highly inaccurate estimations that clutter, confuse and mislead the record

in this proceeding, but instead to the facts and statistics as they really exist within the

files and historical practices of the Illinois Environmental Protection Agency. These

facts will be presented today. They will be based upon a survey of the IEPA’s own data

and files. They will present statistically significant findings and the means and methods

used during this survey will be provided at the hearings and will be transparent to all.

Page 3 of 49

These facts and statistics will establish a clear and competent record; one that can be

relied upon. The small owner/operator also needs the Board to listen to and consider the

proposed solutions to those conceptual flaws contained within this rule.

Finally, the small owner/operator, who is clearly the real beneficiary of a properly

crafted rule, or the collateral victim of a poorly or casually crafted one, wants you to

understand and to act. They want you to understand that they have long suffered the

many contrary, unpopular and bureaucratic requirements of this Agency. They want you

to understand that through the protections and services historically afforded by their

consultants they have been able and willing to tolerate and suffer through the process.

They want you to understand that they consider a threat to the well-being of their

consultants to be a threat to their own well-being. They also want you to act. They want

you to act based upon the adjusted record. They want you to act to alter the existing rule

by modifying it to provide an objective rule based upon sound and transparent

methodologies. They want the rule to be fair, easy to understand and they want it to be

administered fairly and uniformly. They want the rule to represent a true process that

ensures their protection into the future, not just the first engagement in a series of rate

adjustment confrontations. They want you to act now. They want you to act to protect

their safety and welfare. They want you to instill their faith in good government. They

want to avoid an unworkable and intolerable rule moving to second notice. They want to

avoid the need for legislative or judicial intervention. They want you to know that they

are proud and independent, and they want you to know, hopefully unnecessarily, that if

the key provisions of this rule remain so fundamentally flawed, they will quickly and

loudly arise from their silence to right themselves and protect their welfare.

Page 4 of 49

Before moving into the heart of our testimony today, on behalf of the employees

of USI, I want you to know that we are with the small owner/operator. We always have

been and we always will be. Inherent to our mission is the protection of their interest,

their well-being, their property values and their peace of mind, and we are devoted to that

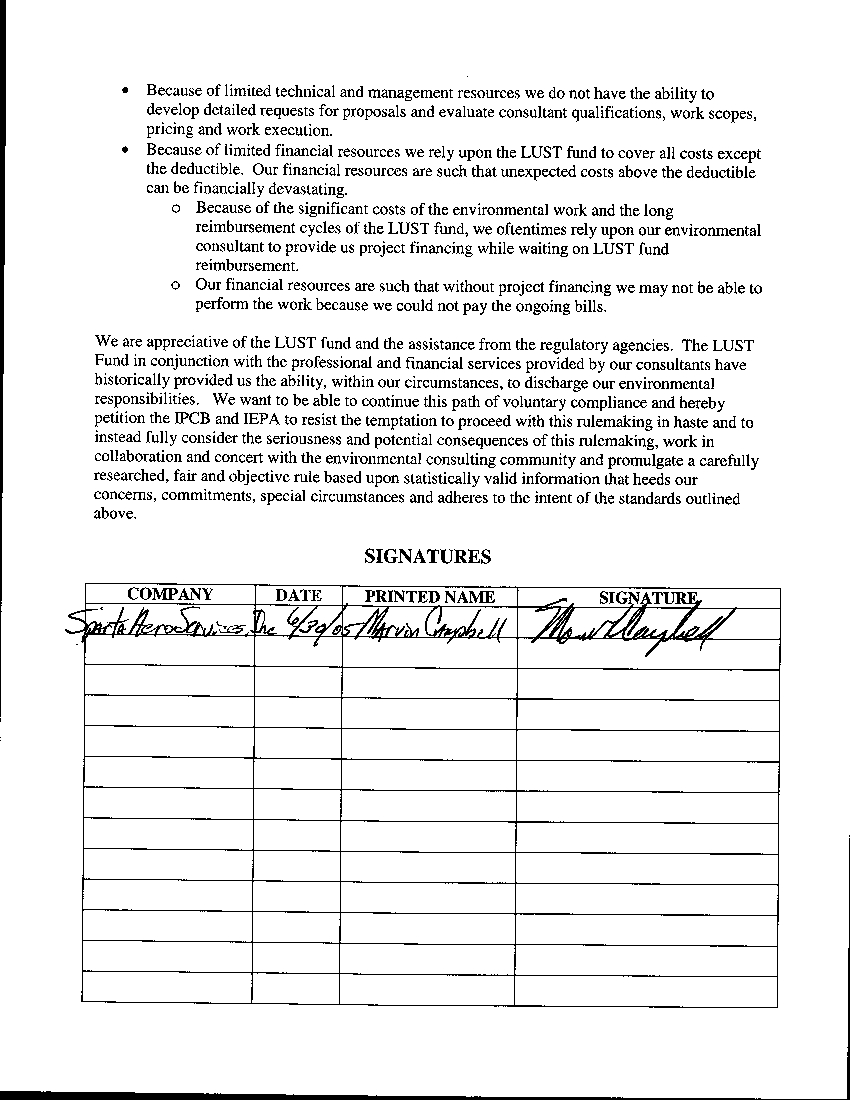

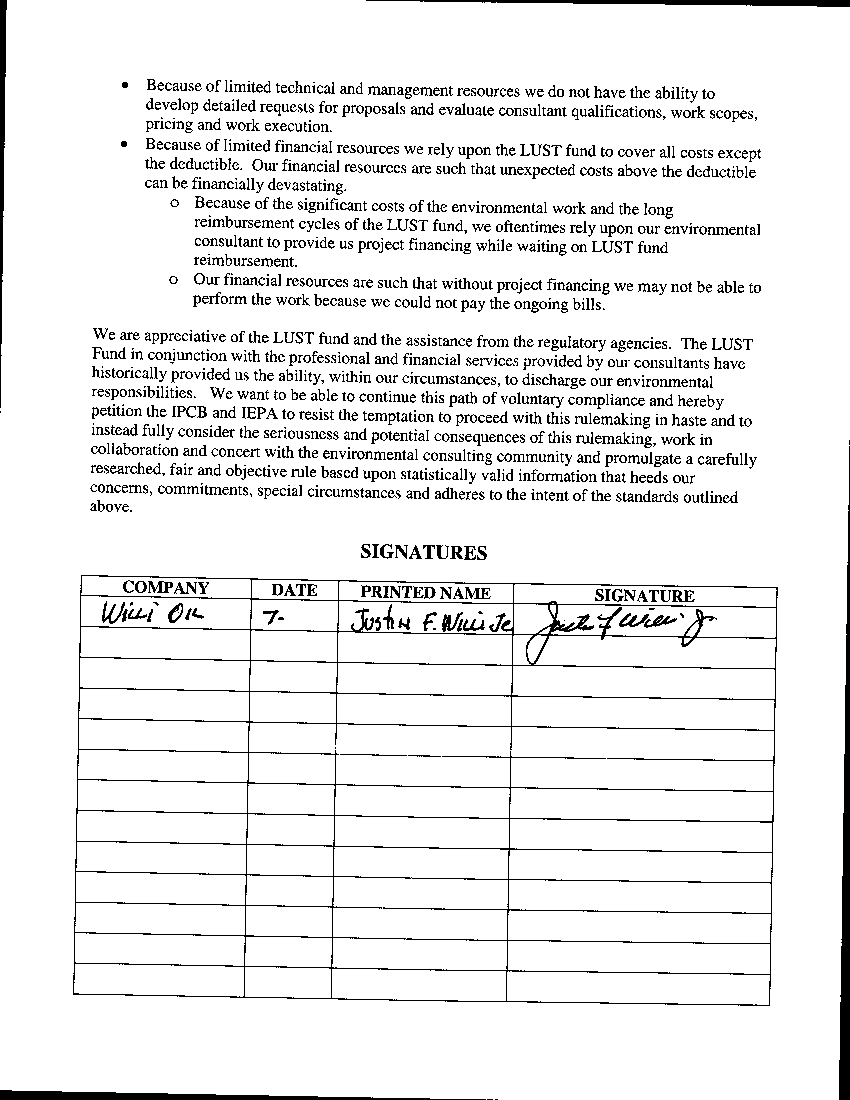

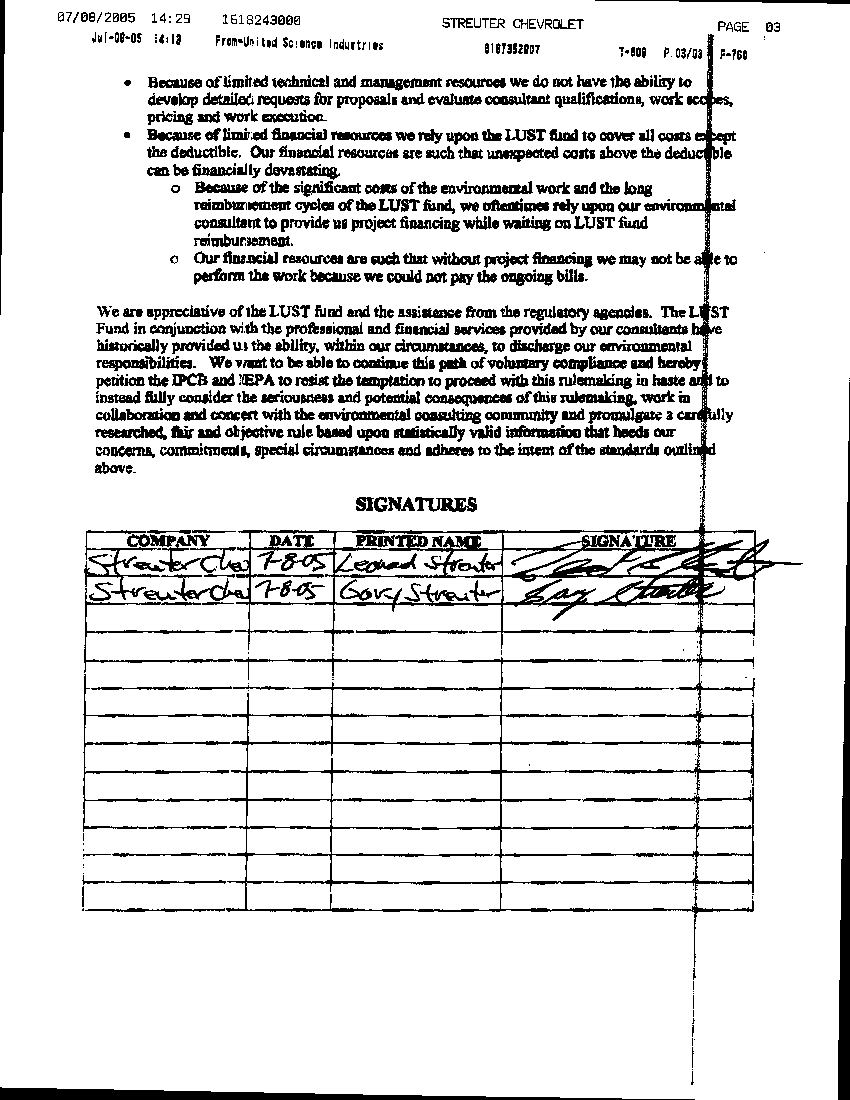

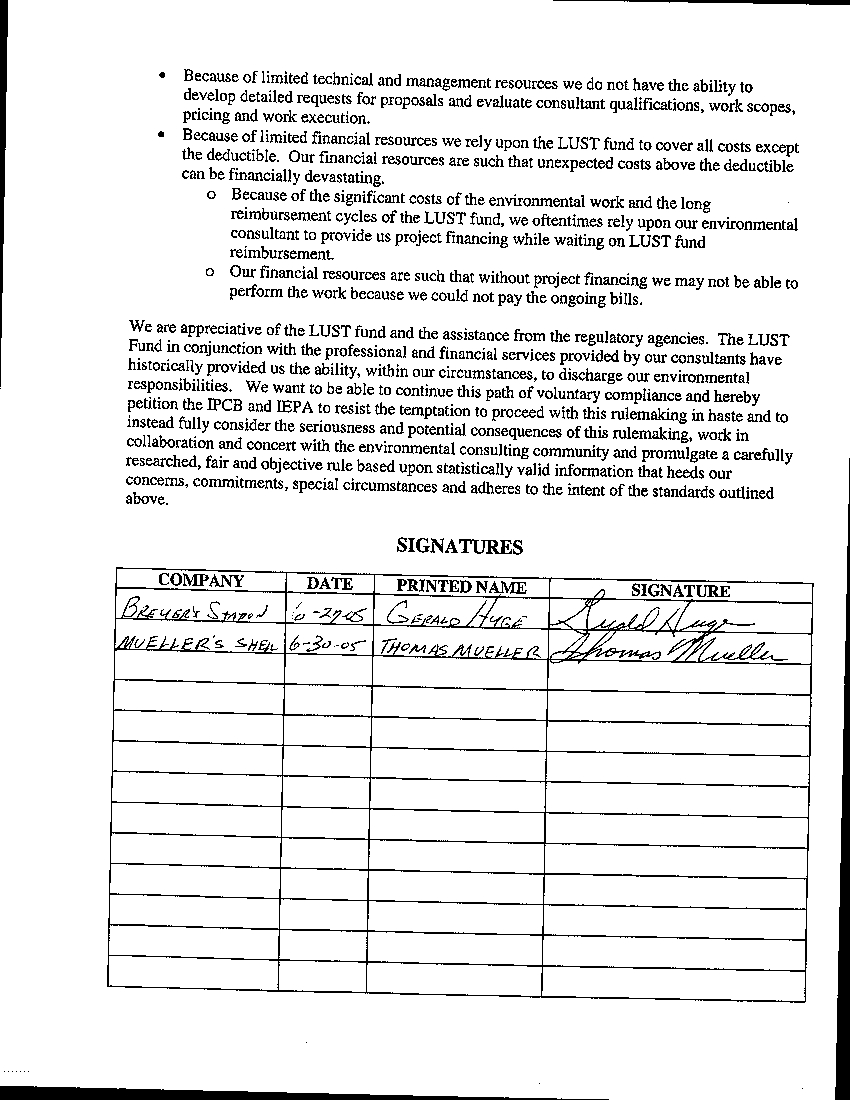

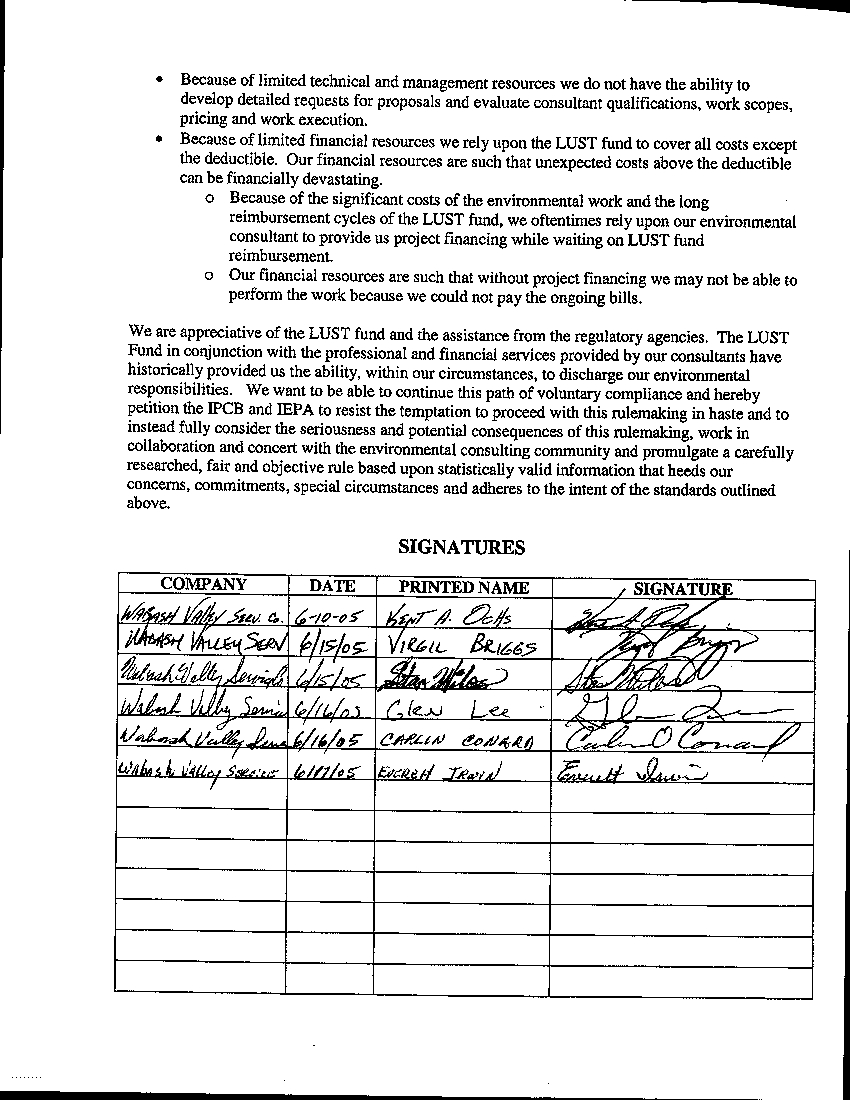

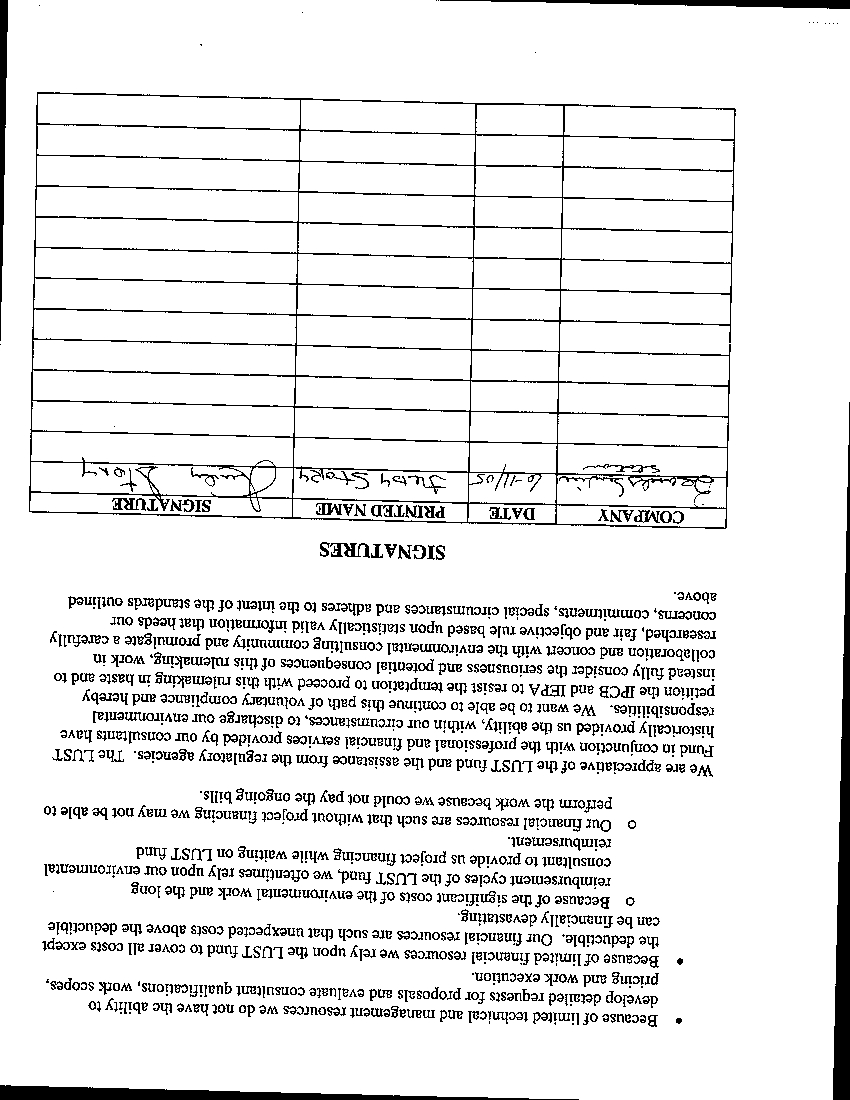

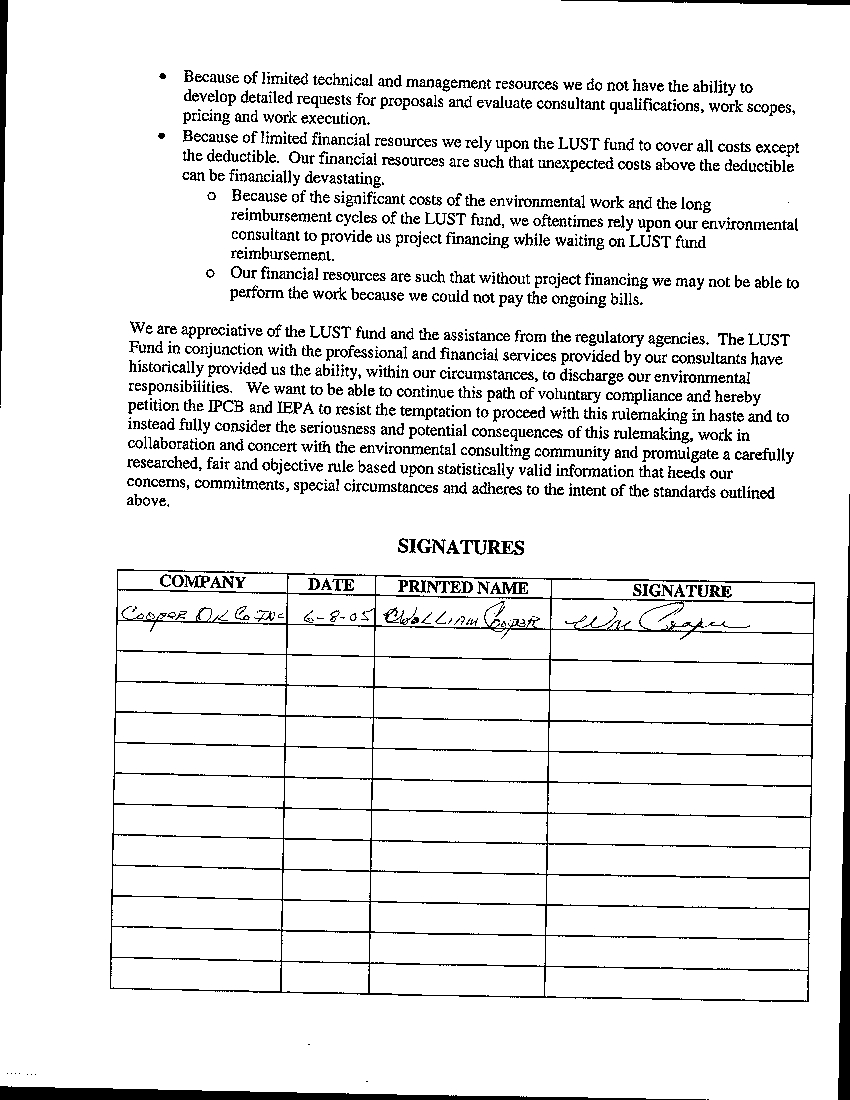

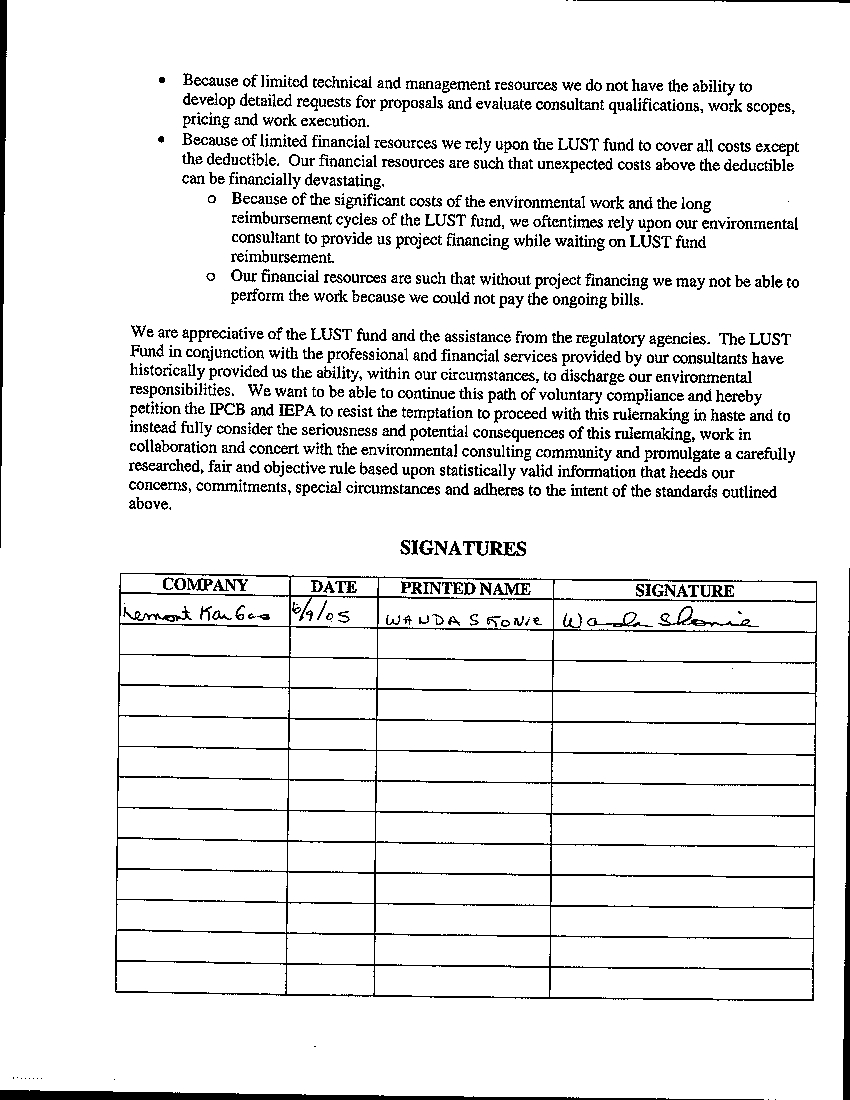

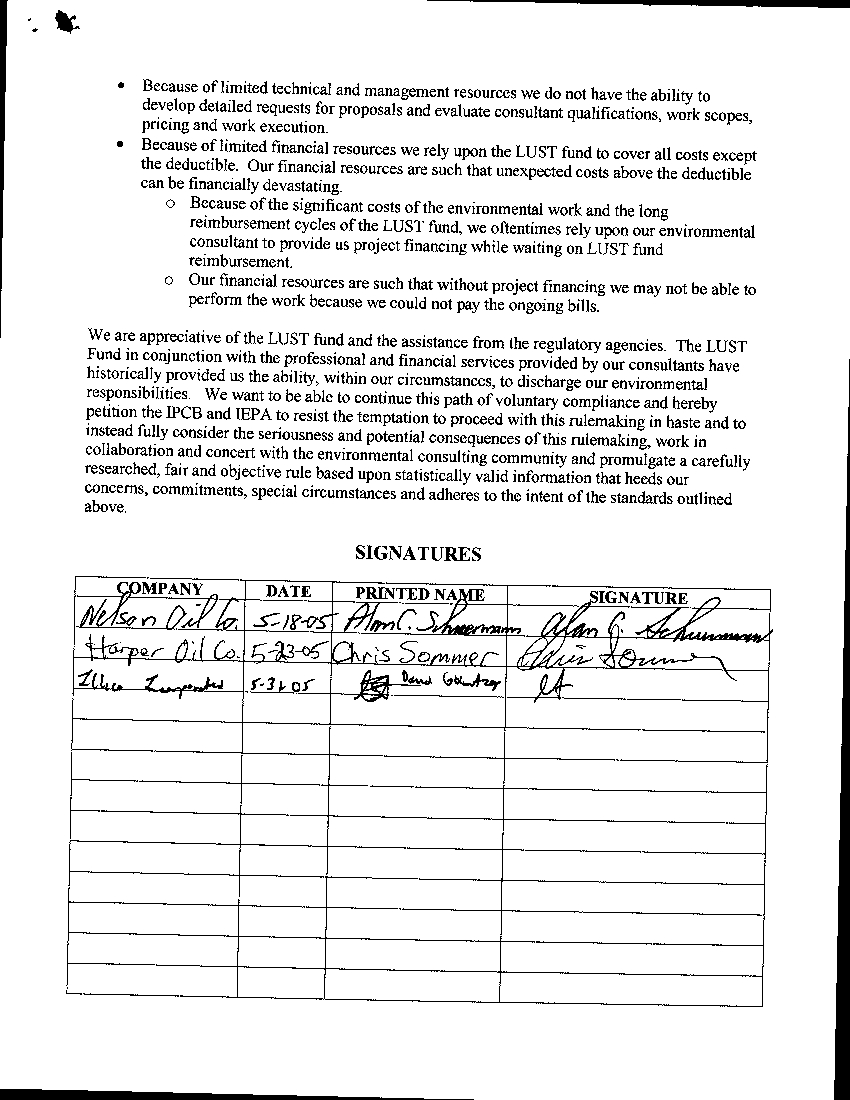

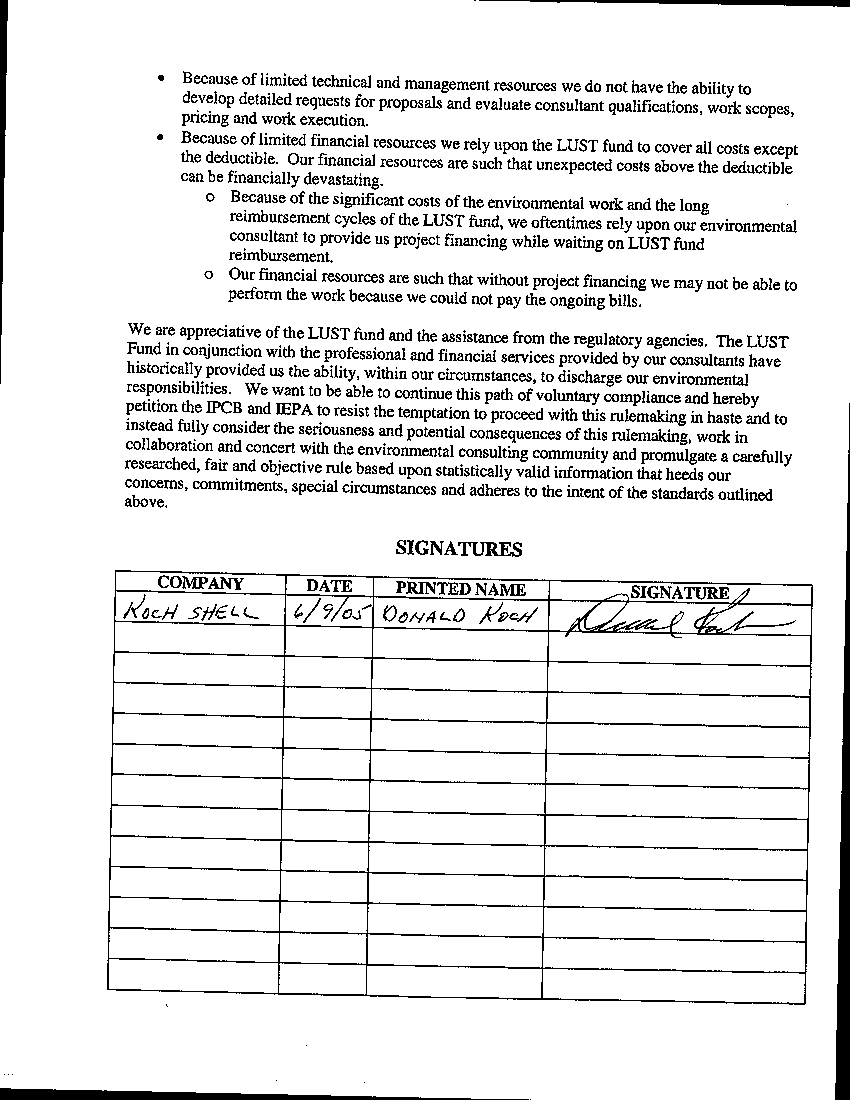

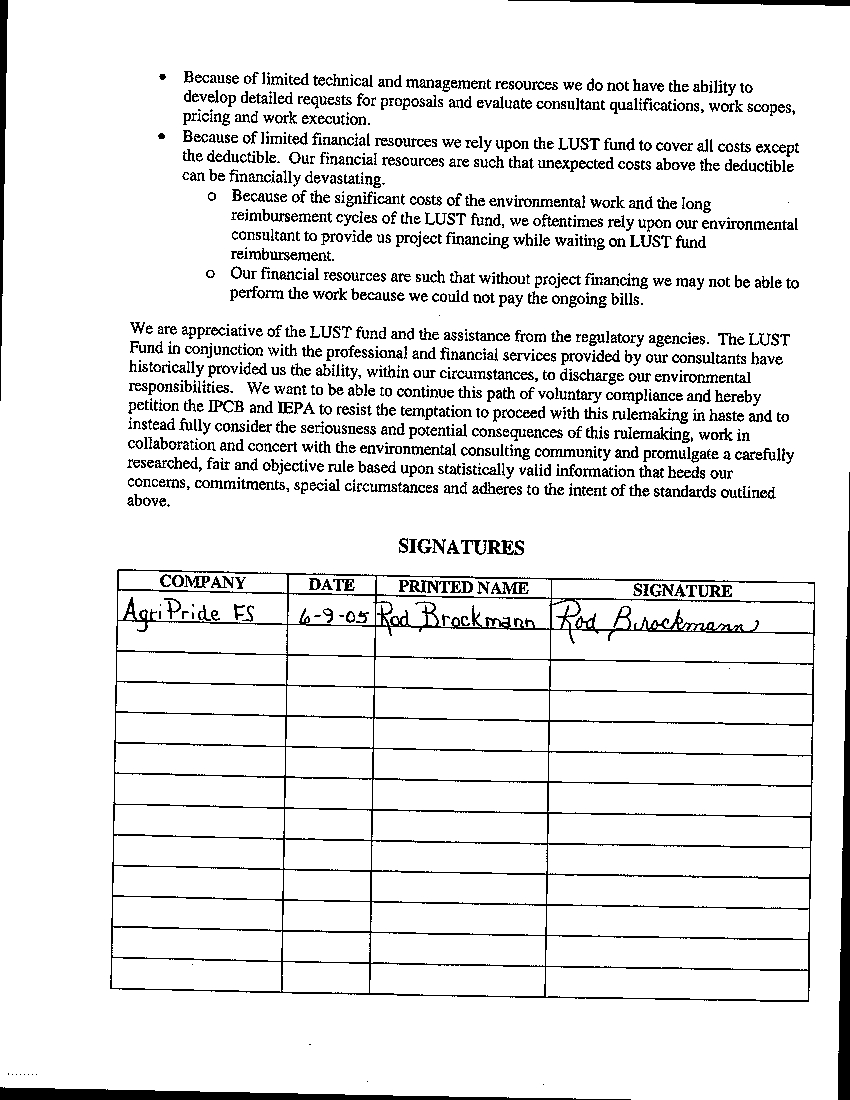

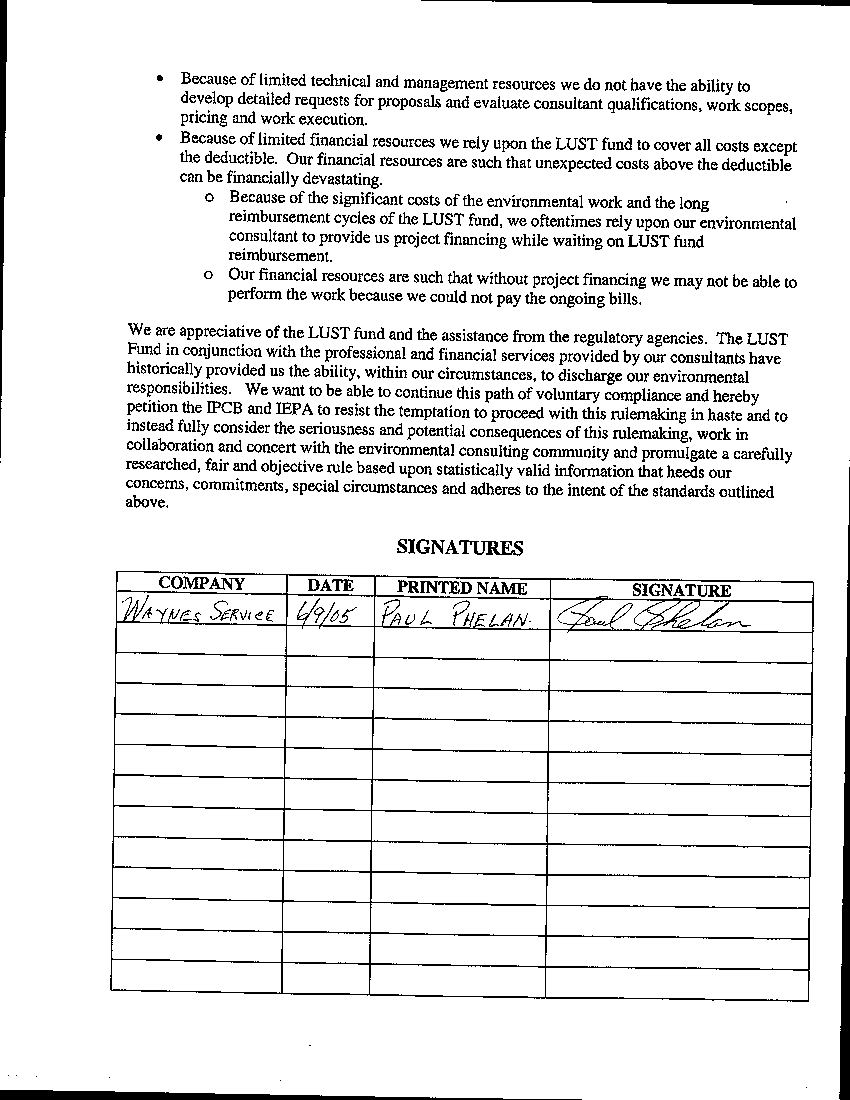

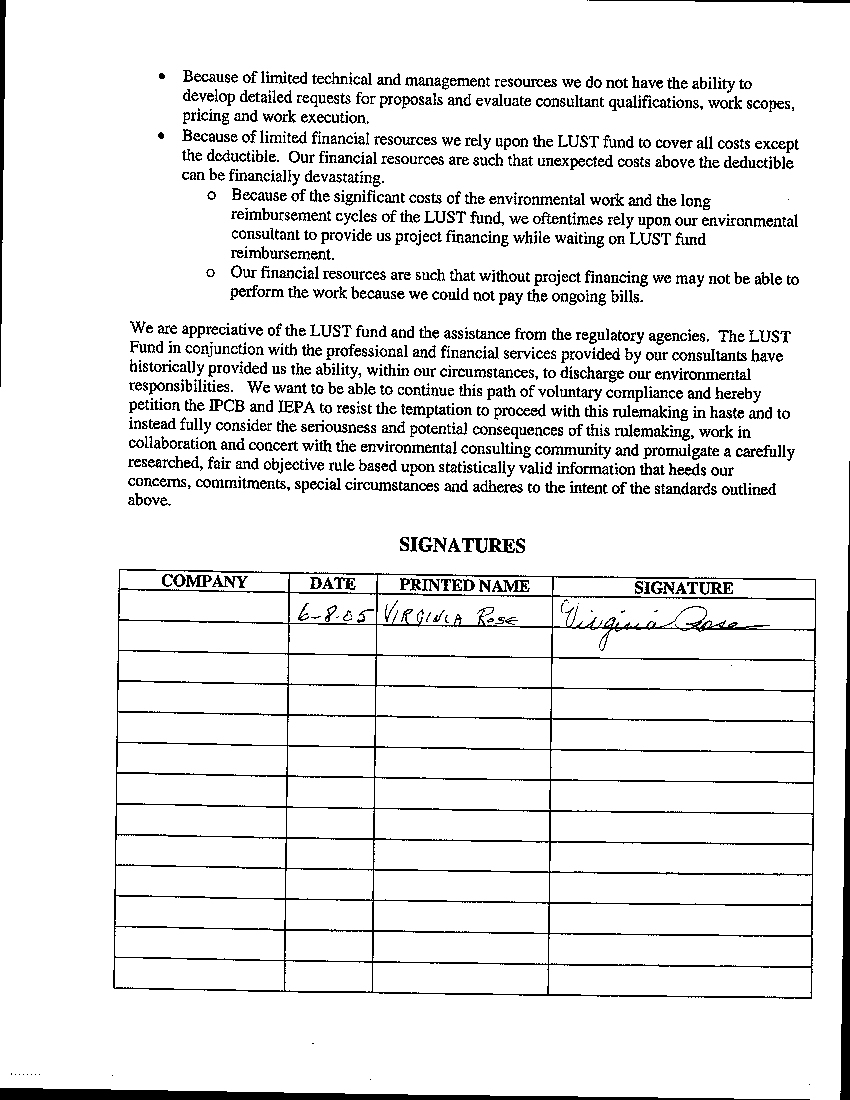

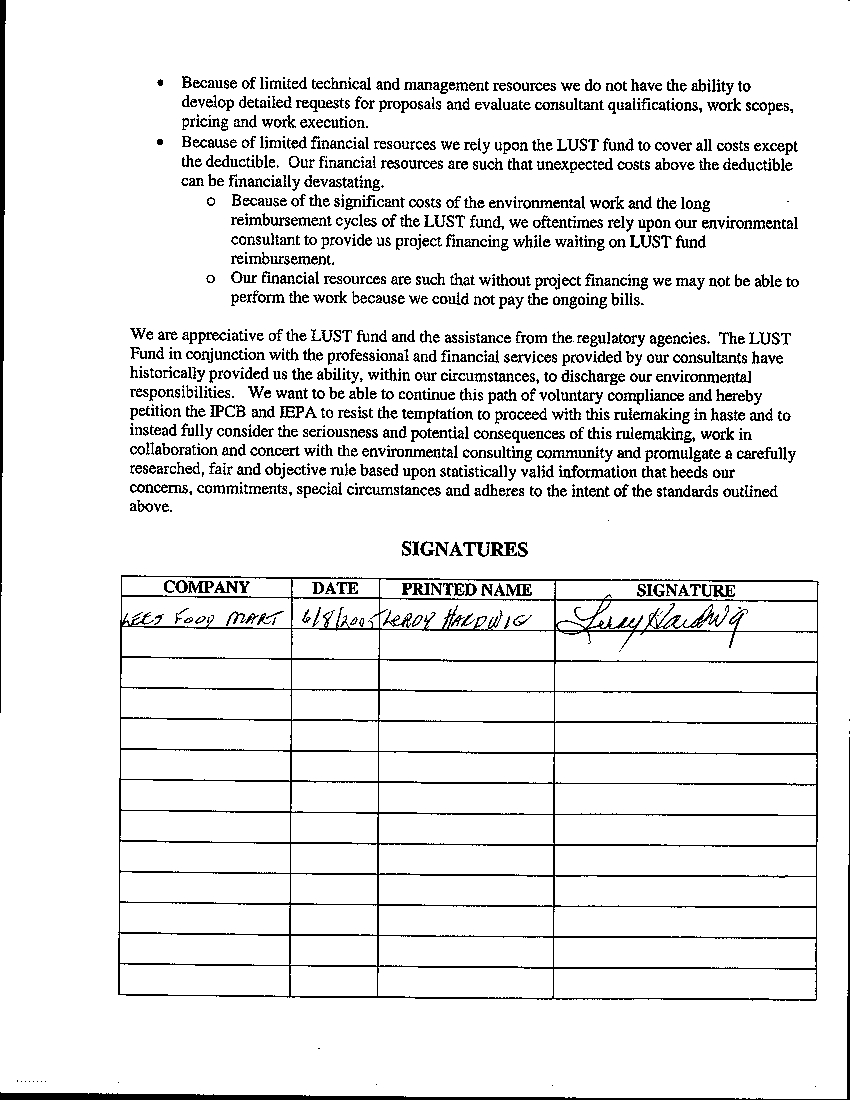

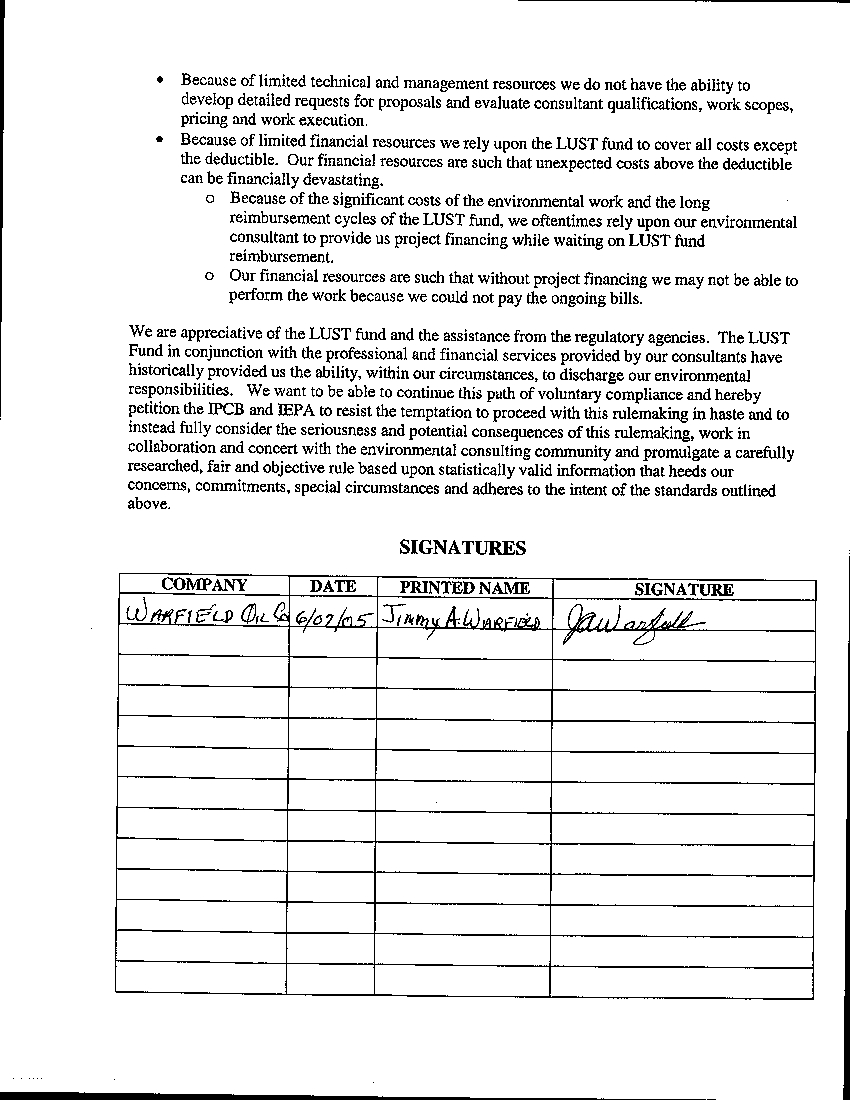

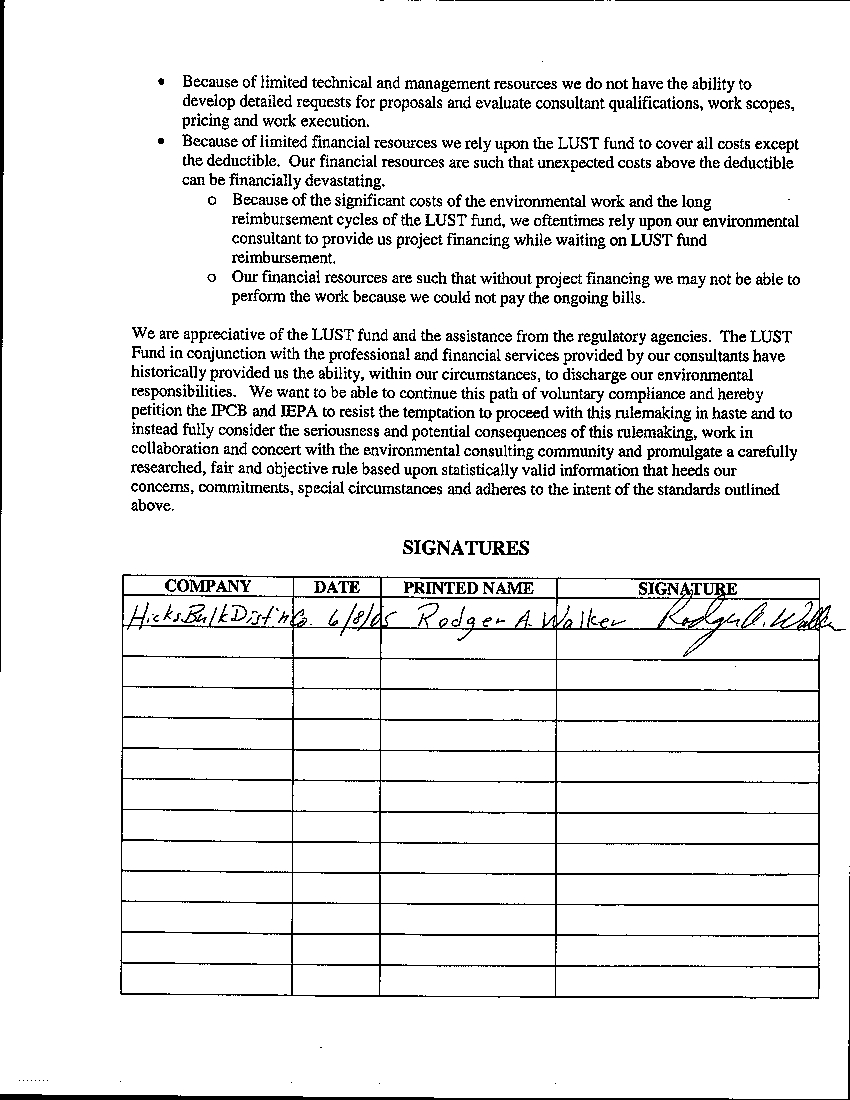

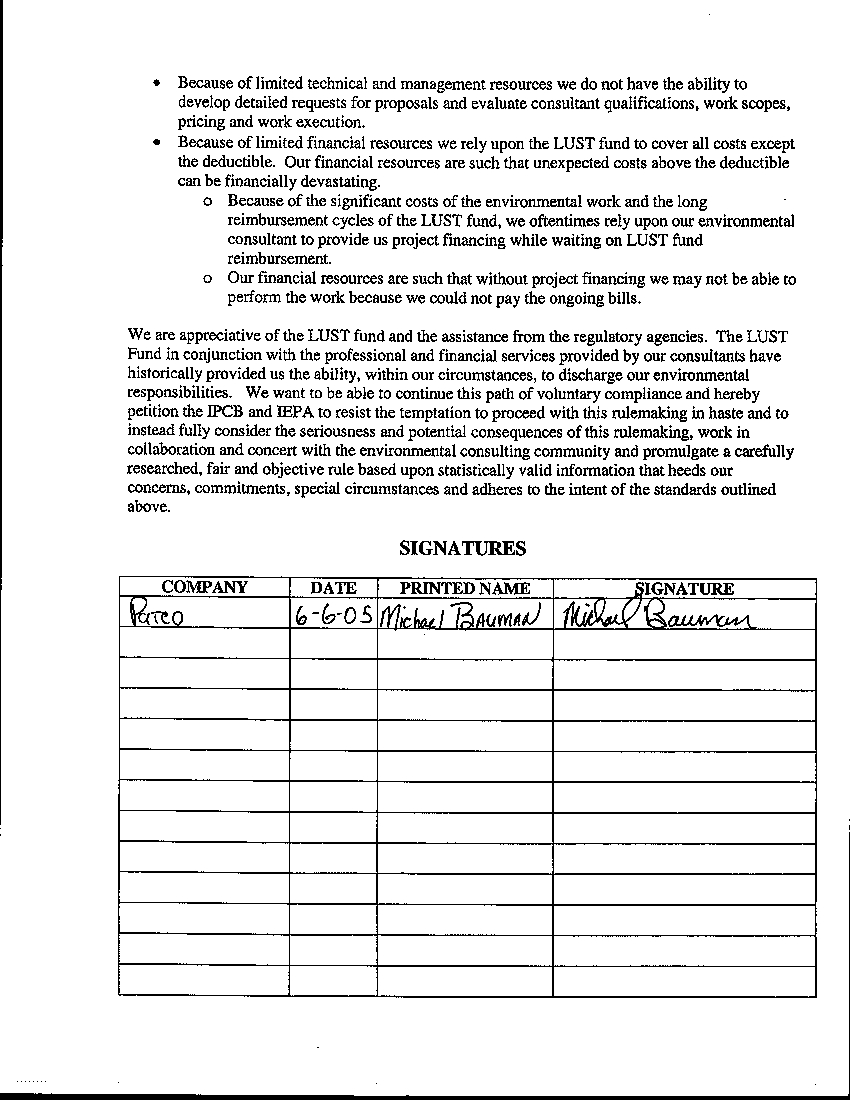

mission. See Attachment I which shows a Petition signed by 100 Owners and Operators

which clearly outlines for the board some of the needs of the owners and operators.

During its testimony today, United Science Industries, Inc. will do the following:

1.

Demonstrate that the class of underground storage tank owner/operator

described above represents the majority of owners/operators across the

state, and provide the Board with a more thorough understanding of

the characteristics, traits and needs of these small owners/operators.

2.

Review the Agency’s originally stated reasons for this rulemaking.

Compare the Agency’s stated reasons to the record and provide

suggestions as to what the industry believes the Agency’s real motives

may be.

3.

Provide factual information that will set the record straight as to the

historical reimbursement practices of the Agency in regard to the

reimbursement/payment of professional services and approval of work

plans and budgets. This testimony will establish that, at least in the

case of professional services, the Agency’s previous testimony

claiming that the rates proposed in Subpart H are “generally

consistent” with the rates the Agency currently approves (Opinion and

Page 5 of 49

Order; page 15, reference to testimony of Doug Clay) is inaccurate and

cannot be relied upon.

4.

Provide a synopsis of the areas within the proposed Subpart H, that are

not objectionable as written, or that are acceptable with minor

modification; noting proposed alternate language, if any, for each such

provision.

5.

Identify the key portions of the rule that are conceptually flawed,

unworkable and intolerable and explain why each such provision is

unworkable.

6.

Provide proposed modifications to the conceptually flawed portions of

the rule based upon simple and fundamentally sound management

practices that will allow this rulemaking to be fair, uniform, and

transparent and that will allow it to serve as a solid foundation for long

term cost containment.

7.

Provide other miscellaneous comments.

Section 1-

Importance of 1-2 Incident PRPs and their Consultants

The following testimony is being presented to quantify and highlight the critical

importance and unique characteristics of a distinct class of open incident potentially

responsible parties (PRP). That class is comprised of the PRPs responsible for only 1-2

open incidents (PRP 1s or Small Owner/Operators). During this testimony we will

present evidence that validates the importance and need of:

Page 6 of 49

•

Small Owner/Operators relevant to reducing overall LUST liabilities in the State

of Illinois;

•

The Illinois Pollution Control Board (IPCB) and Illinois Environmental

Protection Agency (IEPA) promulgating LUST regulations that address the

specialized needs of Small Owner/Operators and the potential severe

consequences if those needs are not addressed; and

•

The unique role of consultants in managing Small Owner/Operators sites and the

need to maintain the integrity of that role.

This testimony is based upon the information obtained from the IEPA Lust database

and other relevant sources during July of 2005.

Total Incident/PRP Data

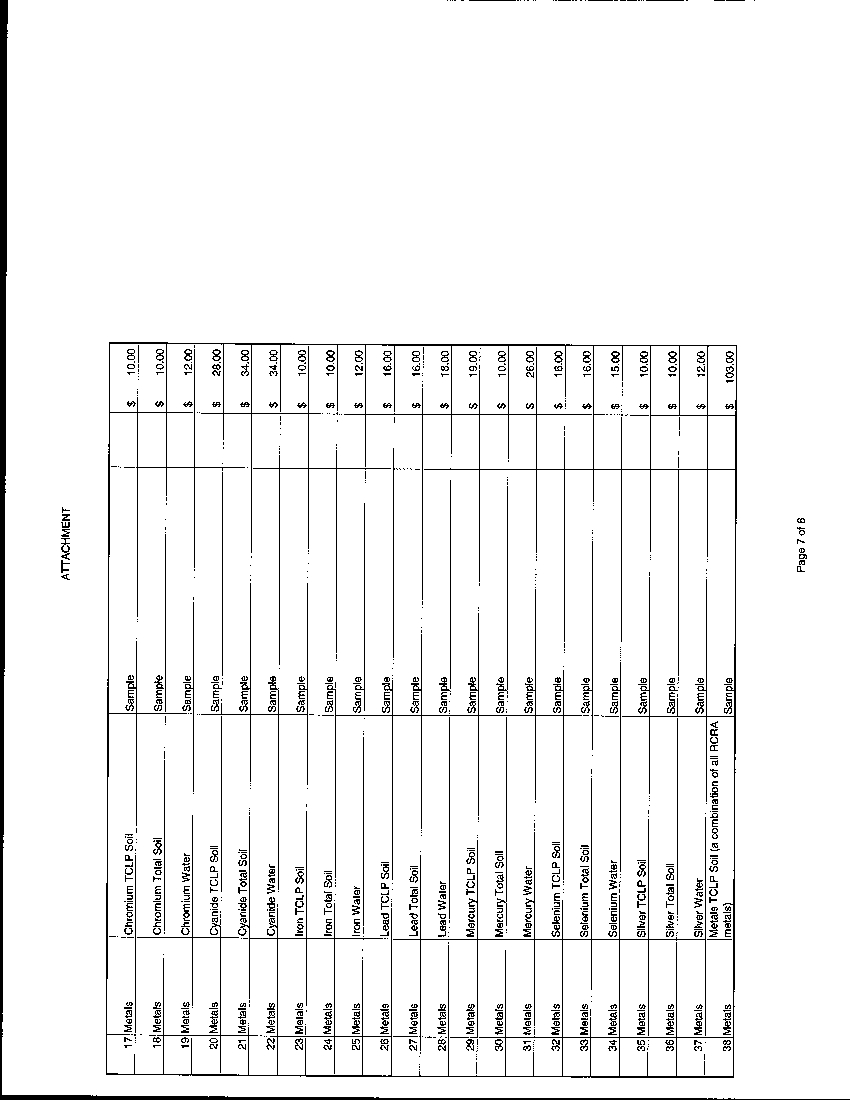

The attached charts 1 and 2 provide a breakdown of total incidents and related PRP

information segregated into the three categories of:

•

PRPs with 1-2 open incidents (Small Owner/Operators);

•

PRPs with 3-20 open incidents (PRP 3); and

•

PRPs with >20 open incidents (PRP 21).

Although each class of PRPs exhibits its own unique characteristics, the focus of this

testimony will concentrate on Small Owner/Operators.

In evaluating the data, several key points are as follows:

•

There is a total of 8566 open incidents with a PRP listed;

•

There is a total of 5620 PRPs responsible for one or more open incidents

;

and

Page 7 of 49

•

There is a total of 4991 Small Owner/Operators responsible for 5342 open

incidents.

This is equal to 88.8% of all PRPs and 62.4% of all remaining

open incidents.

Small Owner/Operators is the largest single group of PRPs remaining in the

program and are responsible for the majority of all remaining LUST environmental

liabilities in the state of Illinois. They are also, as we will demonstrate later in this

testimony, the group most highly dependent on the LUST funding, the efficiency and

efficacy of the regulatory process and the integrity of their consultant relationship.

They are the single largest group to be impacted by the new LUST regulations

, yet

t

hey

are also the most under-represented group of PRPs.

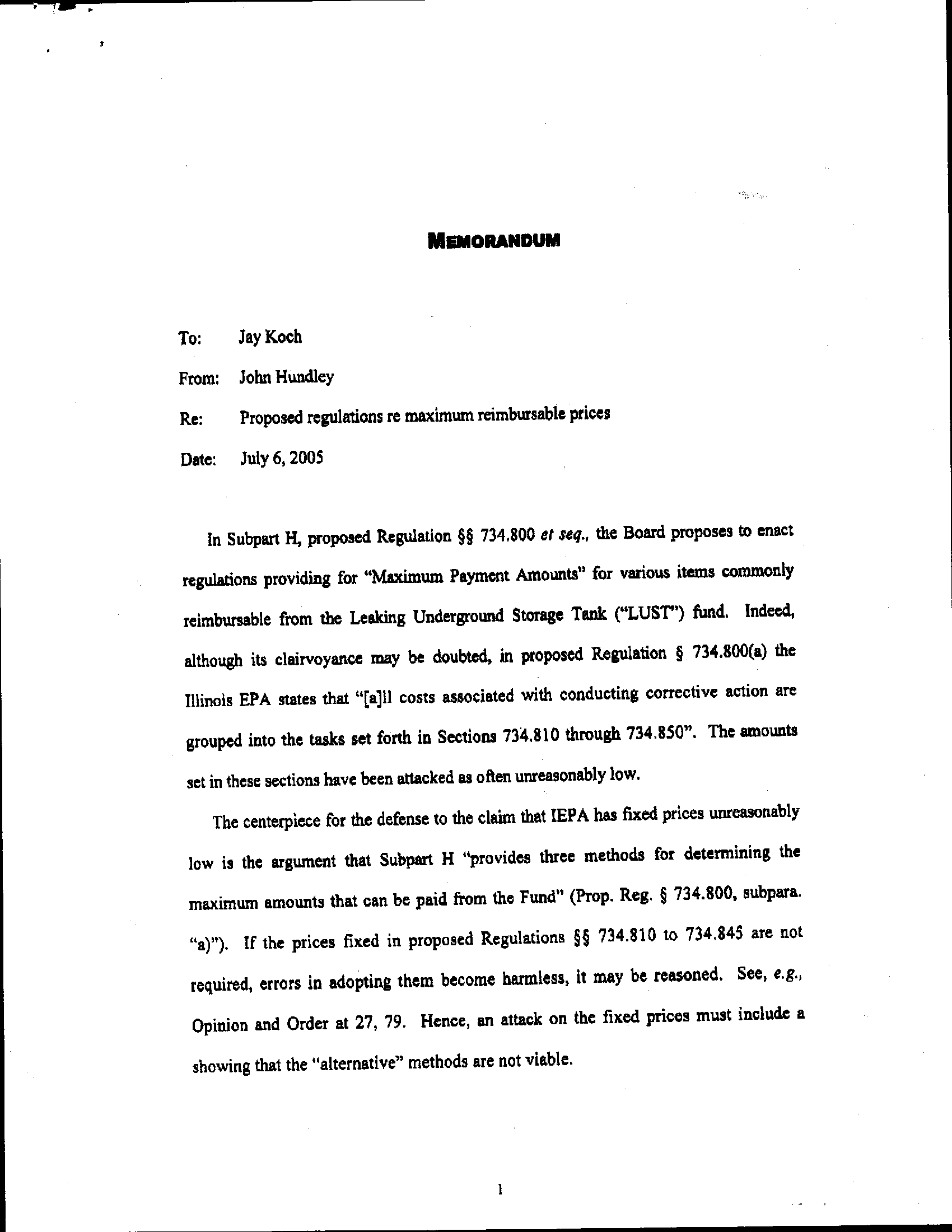

Small Owner/Operators Characteristics

Small Owner/Operators has numerous distinctive characteristics. Although these

characteristics are intuitively understood by anyone with a working knowledge of the

LUST market in Illinois, the characteristics are quantitatively validated by the data

outlined in the attached Chart 3

.

Distinctive Small Owner/Operators characteristics are as follows:

•

Over 19% are listed as individuals;

•

The majority, a total of 67% are businesses. Based on a review of business names

and a sampling of business information, we estimate that the majority are small

to medium sized business owners;

•

The remainder are school districts, government, church and small to medium

sized communities; and

Page 8 of 49

•

For the most part Small Owner/Operators are not represented by key Illinois

organizations. For example, only 1% of Small Owner/Operators are represented

by IPMA.

USI has extensive experience working with Small Owner/Operators. During the past

15 years we have provided services to hundreds of Small Owner/Operators and are

currently assigned 328 open incidents. Some additional key characteristics of Small

Owner/Operators based on our experience include:

•

Their financial resources are typically limited. They are typically unable to meet

financial liabilities above the LUST deductible and oftentimes struggle to meet

the deductible;

•

Their LUST site property is a considered a valuable and oftentimes substantial

component of their assets;

•

They typically have limited management and technical resources, oftentimes

limited to the owner, or more difficult yet, a trustee; and

•

They are proud and responsible individuals who would like to address their

environmental liabilities.

Small Owner/Operators is comprised primarily of individuals, small businesses and

institutions that make up the backbone of our rural and small-medium community

infrastructure. What Small Owner/Operators is NOT, and this is absolutely critical to

understanding the impact of the LUST regulations on them, is they are NOT typically

big business, do NOT have deep pockets, and do NOT have extensive management and

technical resources

.

Addressing their open incident responsibilities places them at

significant financial, legal and resource risk!

Page 9 of 49

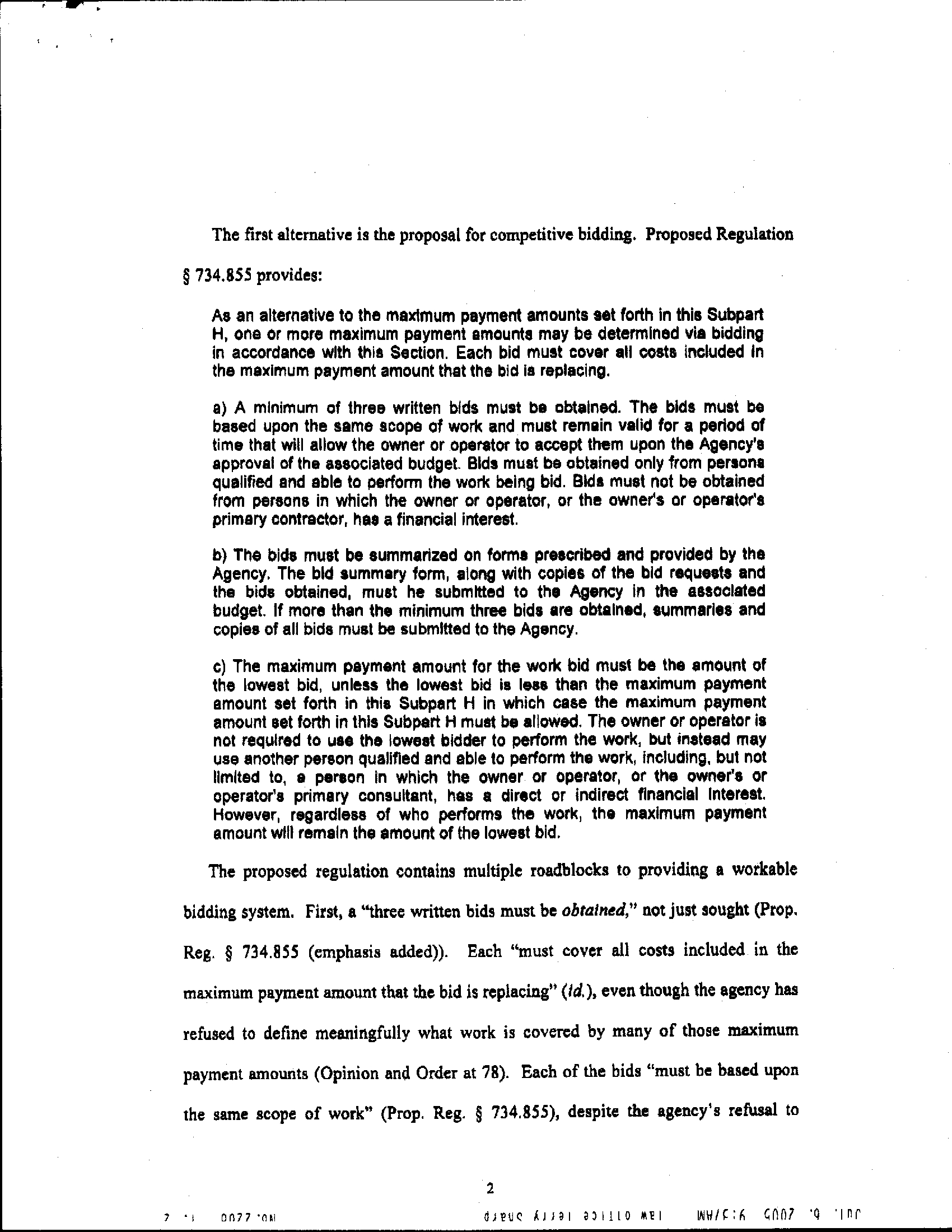

For comparison purposes and to better understand the unique characteristics of Small

Owner/Operators, we performed a similar analysis of the PRP 21 group. This data is

presented in the attached Chart 4 and indicates the following:

•

There are no individuals listed in the PRP 21 group;

•

The majority, a total of 74% are businesses. Most of the businesses are larger

with annual revenues in the millions of dollars;

•

The only community listed in this PRP group is the City of Chicago; and

•

Over 37% of PRP 21 are members of IPMA.

In addition, based on our working prior experience with the PRP 21s, they are several

more distinctive differences from the Small Owner/Operators group including:

•

They tend to have good financial resources. Paying the deductible is not an

overwhelming financial hardship;

•

The LUST site property is oftentimes a limited or negligible component of their

assets;

•

They have more extensive management resources. Larger companies oftentimes

have an in-house environmental manager;

•

Oftentimes they accelerate the project and pay out of pocket for activities not

covered by the LUST fund in order to achieve internal financial/management

goals; and

•

They are oftentimes willing to TACO property and minimize returns from

property sale in order to move property out of inventory.

Page 10 of 49

Although we did not go into a detailed evaluation of the PRP 3 class, it is reasonable

to assume their characteristics are somewhat a blend of the two previously discussed

classes.

In comparison to the larger PRP groups, Small Owner/Operators is highly

dependent on the financial resources provided by the IL. LUST fund. This financial

dependence includes both the need for 100% reimbursement of approved items and

also the need for timely payment. Also, the LUST site property is an important

financial asset and the regulations must allow them to preserve that asset value. And

finally, because of limited management and technical resources, they are highly

dependent on their consultant to manage all aspects of their environmental project.

The unique role of the consultant for Small Owner/Operators is discussed next in this

testimony.

Open Incident Consultant Statistics

To better understand the role of the consultant in working with Small

Owner/Operators, we first evaluated basic information concerning the number of

consultants in Illinois and their primary PRP groups. Key information is as follows:

•

The total number of consultants in IL is 375 as testified in previous hearings by

the IEPA;

•

Of the 8566 total open incidents, 2081 open incidents are currently assigned to

334 consultants

;

•

The number of consultants representing Small Owner/Operators is 321;

•

The top 5 consultants represent 26.7% of the Small Owner/Operators;

Page 11 of 49

•

The top 5 consultants represent over 24.2% of the assigned Small

Owner/Operators open incidents; and

•

Three of the five top consultants are members of PIPE.

United Science Industries is the leader among the top 5 Small Owner/Operators

consultants with a total of 328 assigned open incidents, 204 of which are Small

Owner/Operators open incidents. We have operated successfully in the IL LUST market

for over 15 years. We make this point primarily to verify that we have a deep

understanding of the LUST market and especially the Small Owner/Operators needs.

Our organization has been a leader in developing approaches that address the unique

needs of Small Owner/Operators. The role of a consultant for Small Owner/Operators is

significantly different then for the larger PRP groups.

Key components of the unique role of a Small Owner/Operators consultant include:

•

They are oftentimes sole source for the duration of the project since the Small

Owner/Operators has limited resources and is not able to easily procure or

manage multiple providers;

•

They typically manage all aspects of the work and discussion with the IEPA

based on the Small Owner/Operator’s limited technical expertise and

understanding of the regulations;

•

They discuss optional approaches with the Small Owner/Operators but tend to

implement approaches that help protect property value since the Small

Owner/Operators property is a key financial asset;

Page 12 of 49

•

They very carefully schedule and manage all activities within LUST fund

guidelines to achieve 100% reimbursement due to the financial hardships that

would be experienced by Small Owner/Operators if they were forced to pay

additional monies above the deductible; and

•

They typically wait on payment from the LUST fund since the Small

Owner/Operators does not have sufficient cash flow to pay on standard consulting

payment terms.

Contrast the Small Owner/Operators consultant approach with an approach more

typical to the PRP 21 group and substantial differences will be noted. For example:

•

Consultants typically report to the PRP 21 environmental manager, lawyer or

purchasing agent.

•

Consultants develop and implement approaches that meet PRP 21 overall

objectives including schedule, property disposition, asset management, fiscal year

goals and other key considerations;

•

Managing an approach within LUST fund guidelines to achieve 100%

reimbursement may be only one of multiple considerations mentioned above and

not necessarily the ultimate approach driver; and

•

Consultants typically receive payment on net 30-60 day terms direct from the PRP

21.

PRP 21 has significant internal resources and the open incident site is oftentimes not a

critical part of their asset base. Although they rely on their consultants to achieve

regulatory compliance in a cost effective and technically correct manner, their approach

to site closure is driven more by overall goals as compared to site specific considerations.

Page 13 of 49

In comparison to larger PRP groups, Small Owner/Operators is highly dependent

on their consultant of choice. Oftentimes the relationship is significantly trust based

with Small Owner/Operators relying on the consultant to ensure they meet regulatory

requirements in a manner where they are not faced with legal liabilities, are not

required to pay monies in addition to the deductible, and where their long-term

property values are protected.

In order for the consultant to accomplish these goals, the regulatory process must

recognize the unique needs of Small Owner/Operators and the necessity to maintain

the integrity of the consultant/owner relationship. In addition, the reimbursement

process must provide timely payments to ensure the Small Owner/Operators and their

consultants are able to move forward with the work at a reasonable pace without

suffering devastating cash flow drains.

Conclusions

Small Owner/Operators is the single largest PRP group responsible for the

majority of the open incident sites in Illinois. As a group they have definite and unique

needs that must be addressed if they are to be successful in achieving environmental

compliance on their sites.

We feel it is imperative that the IPCB and the IEPA take action to provide regulations

that address the special needs of Small Owner/Operators, their largest group of

customers. Those actions include:

•

Providing a streamlined and efficient LUST program that ensures 100%

timely payment for all approved activities above the applicable deductible.

A

program that continuously delays payments and places payment amounts in

Page 14 of 49

jeopardy based on arbitrary and unsubstantiated requirements can bankrupt the

Small Owner/Operators.

•

Providing an efficient and functional LUST program that recognizes and

maintains the stability of their unique owner/consultant relationship

. Dealing

with regulations and payment “catch 22s” that necessitate ongoing competitive

bidding and potential consulting changes is beyond the management resources of

the Small Owner/Operators.

•

Providing regulations that recognize and address the critical need of Small

Owner/Operators to maintain long-term property value

. Regulations that

force Small Owner/Operators to close sites at contaminant levels that reduce or

eliminate property value can be financially devastating.

Ignoring these needs in form or substance is basically ignoring a class of individuals,

businesses, and public entities that are at the heart of our American culture. These are

truly the entities that helped build our great state and nation and should be the primary

recipients of the benefits and value of the LUST program funding. Ignoring these needs

places Small Owner/Operators at significant financial risk and jeopardizes the majority of

the LUST environmental work to be completed in Illinois. Although the larger PRP

groups probably have the resources to survive poorly crafted, indifferent and bureaucratic

regulations, under those circumstances Small Owner/Operators must either not perform

the work and face legal liabilities or perform the work with the risk of significant

financial losses and excruciating drains on internal resources.

This unique class of PRP deserves your comprehensive attention to the details that

will make the program work for them. They are at the heart of the Illinois LUST

Page 15 of 49

program and it is incumbent upon us as consultants and you as regulators to respond to

their needs.

Final Remarks

The information and conclusions provided in this testimony is further

corroborated and supported by the 100 signed petitions from PRPs and testimony from

selected PRPs all requesting a fair, equitable and statistically sound approach to the new

regulations that take into account the unique characteristics of the Small

Owner/Operators-group.

It should also be stated that addressing the unique needs of the Small

Owner/Operators group can and should be accomplished without comprising in any

fashion the need for the IEPA to manage a LUST program that is efficient and effective,

incorporates reasonable cost controls and achieves environmental regulatory compliance.

More information concerning this is provided in other sections of this testimony.

Page 16 of 49

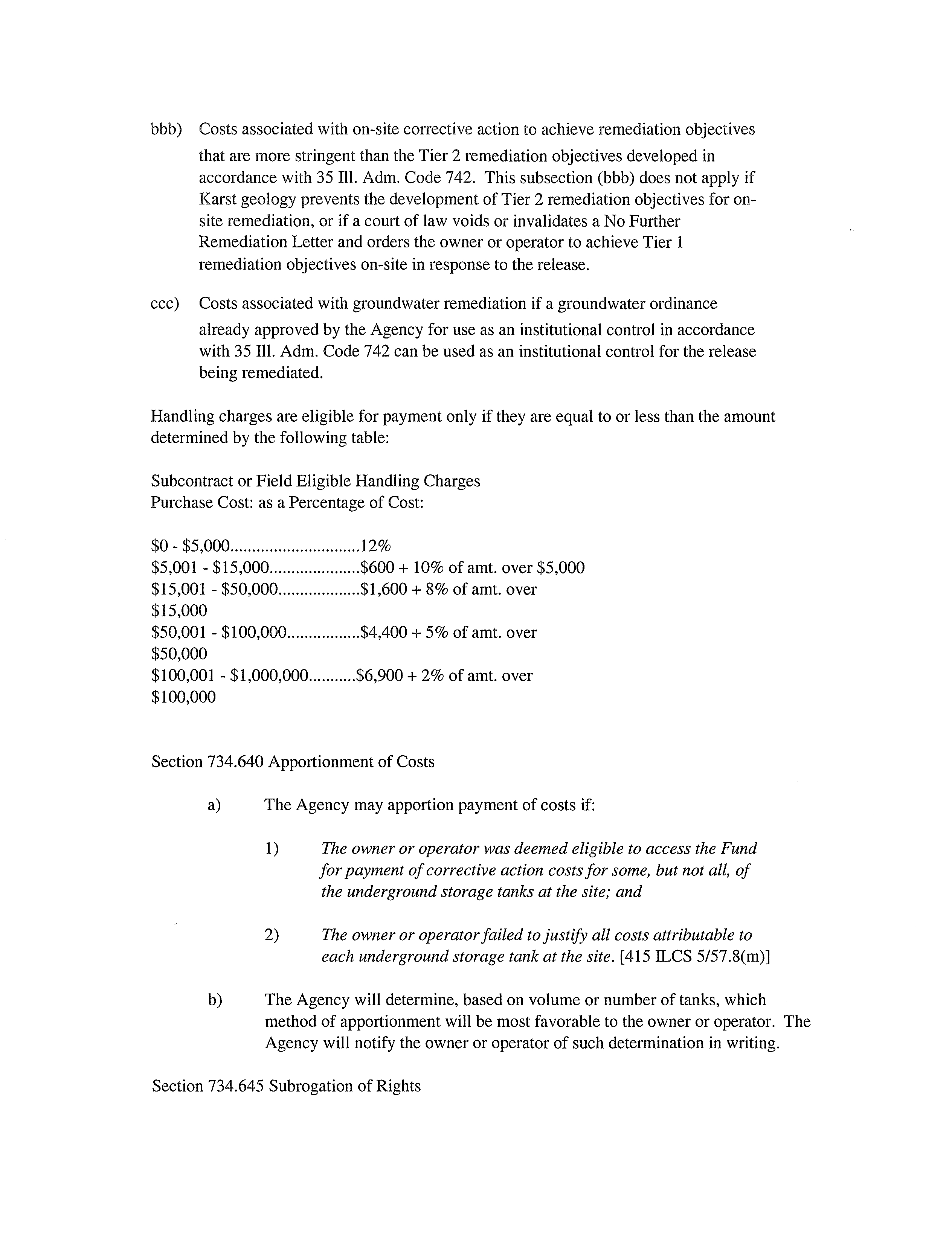

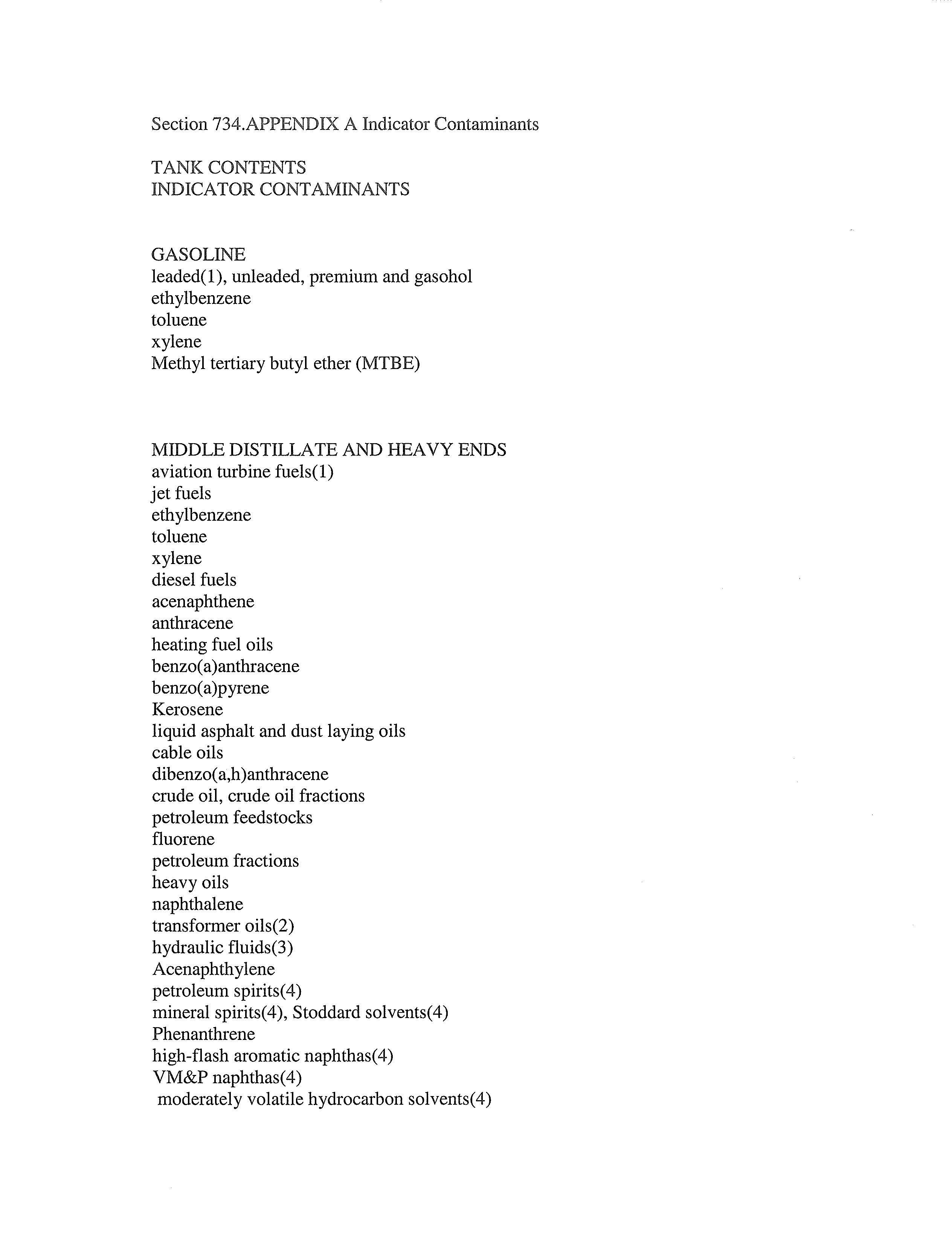

Chart 1

5342, 63%

1473, 17%

1751, 20%

PRP 1

PRP 3

PRP 21

Note:

Total number of

Open Incidents is

8566.

Open Incident Data by PRP Group

Note:

Chart 1 outlines

open incident

data obtained

from the IEPA

database in July

of 2005.

Page 17 of 49

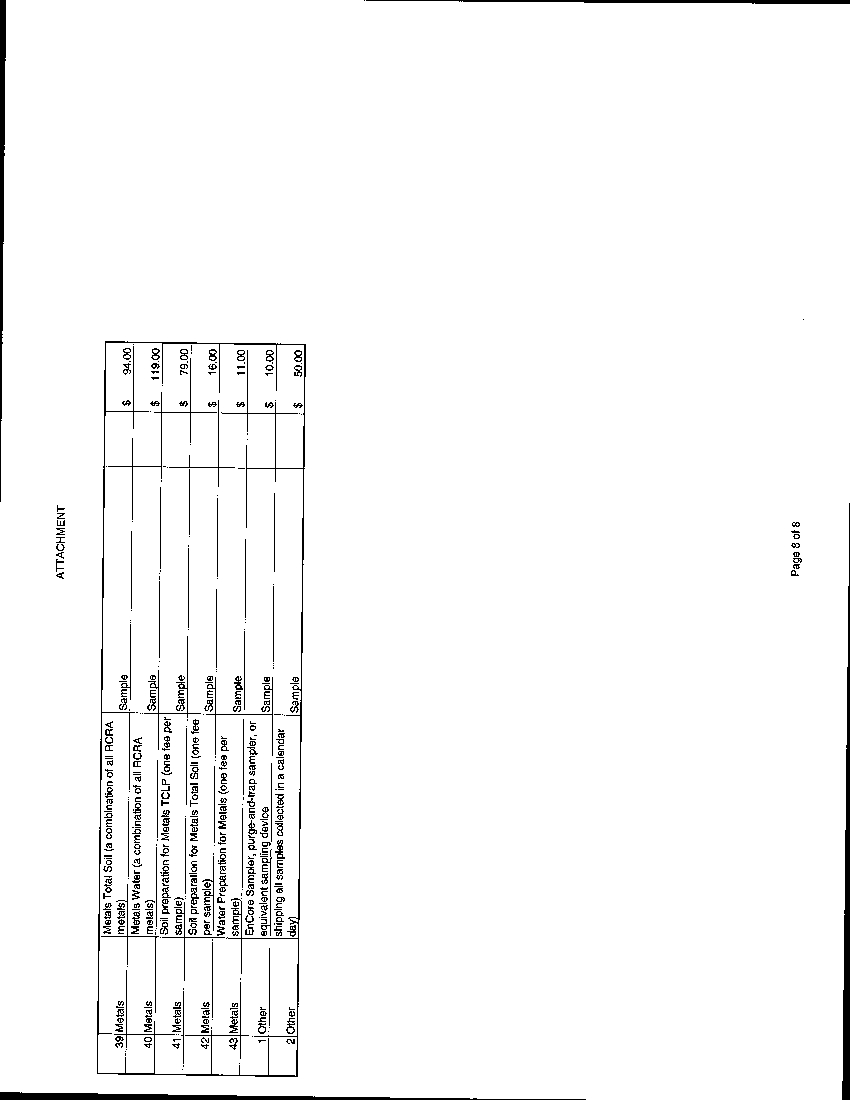

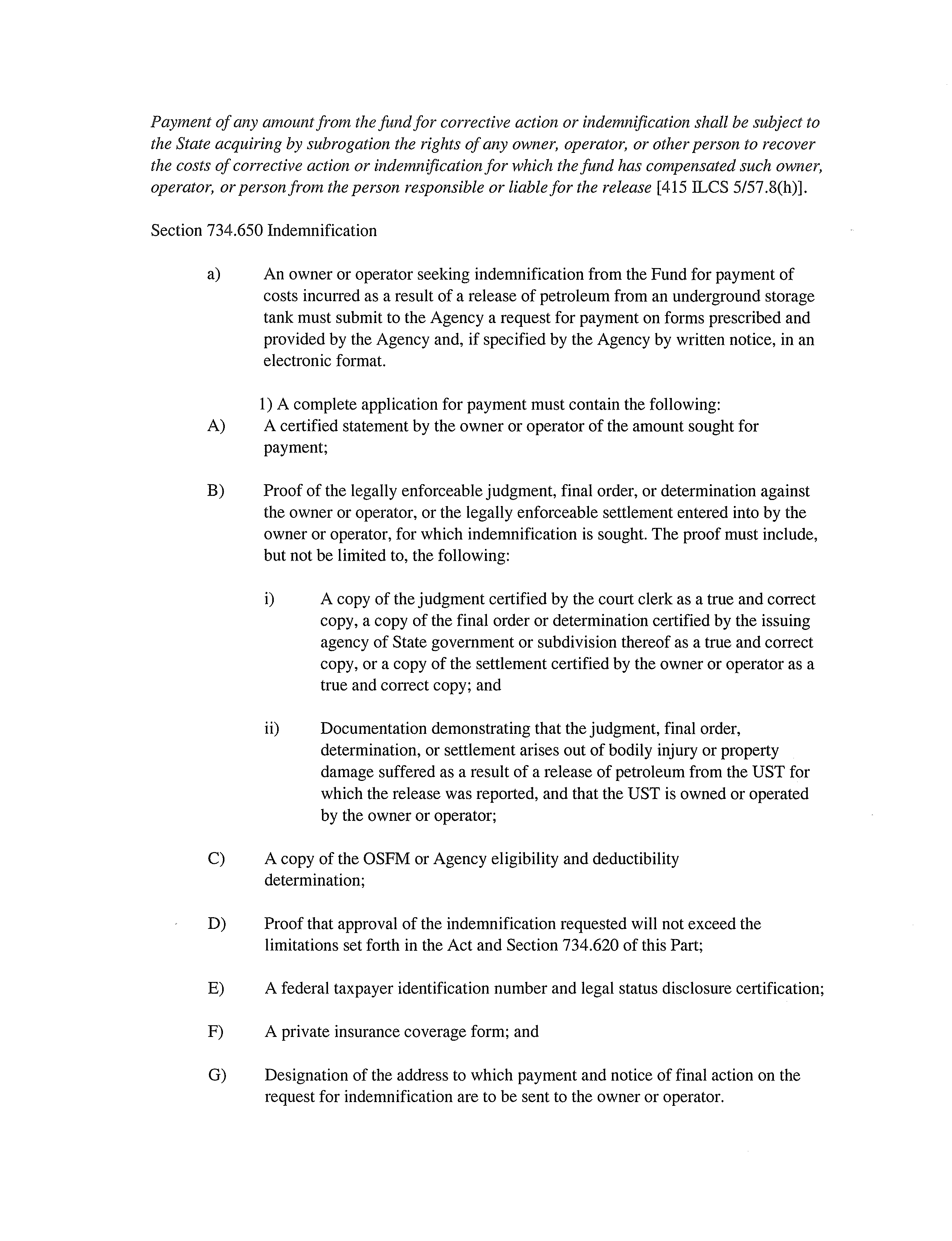

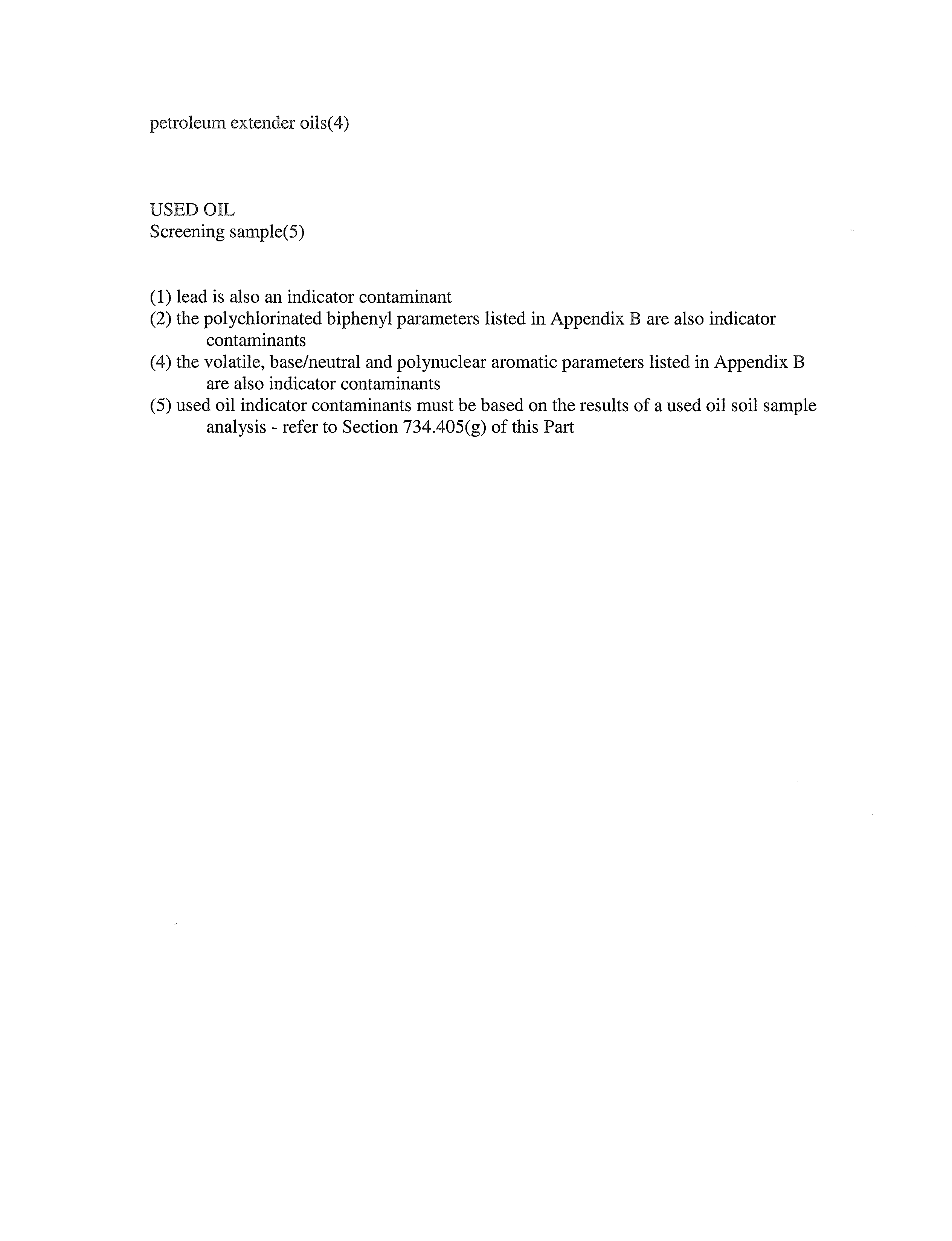

Chart 2

4991, 89%

578, 10%

51, 1%

PRP 1

PRP 3

PRP 21

Note:

Total Number

of PRPs is

5620.

Total PRP Data by PRP Category

Note:

Chart 2 outlines

PRP information

obtained from the

IEPA database in

July of 2005.

Page 18 of 49

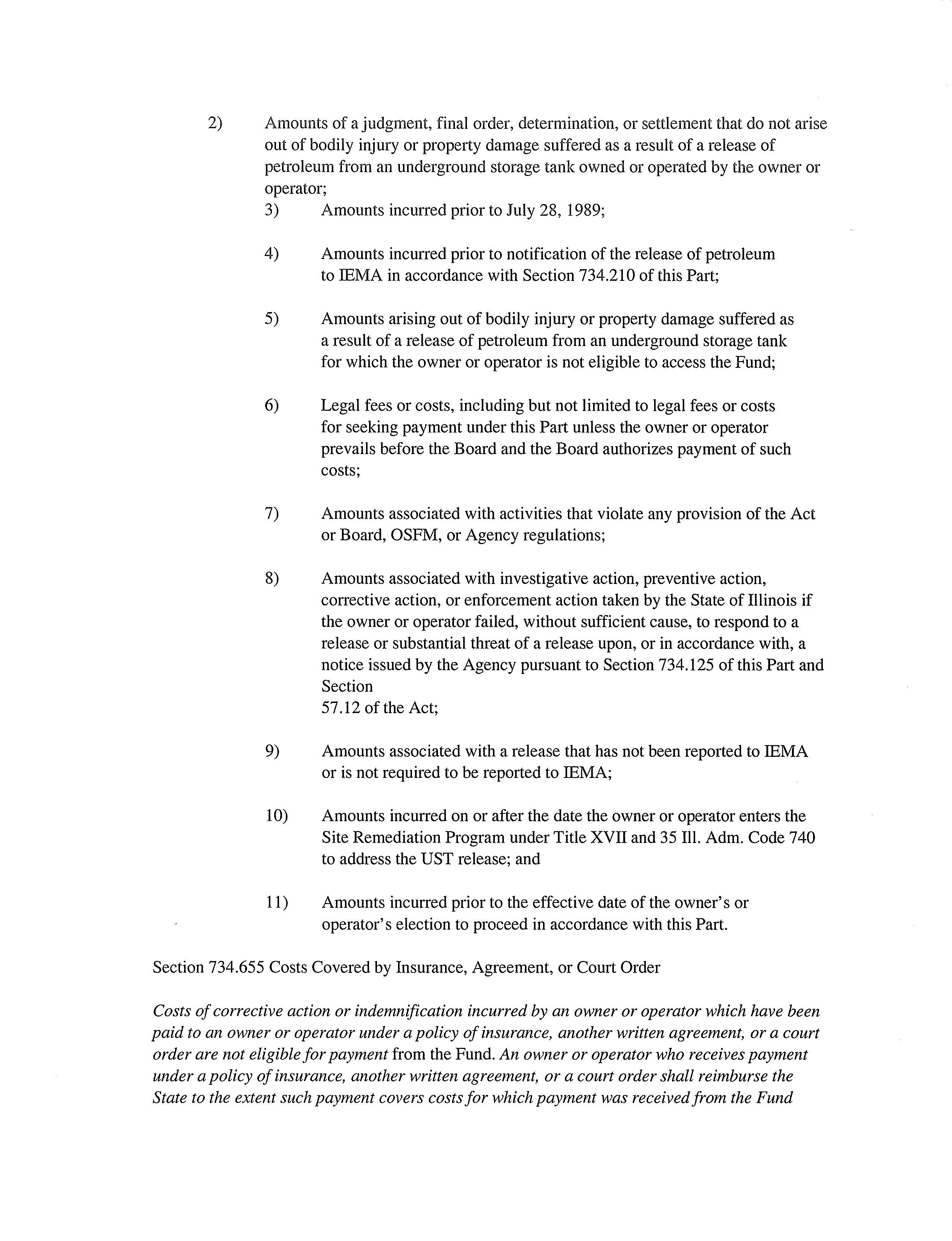

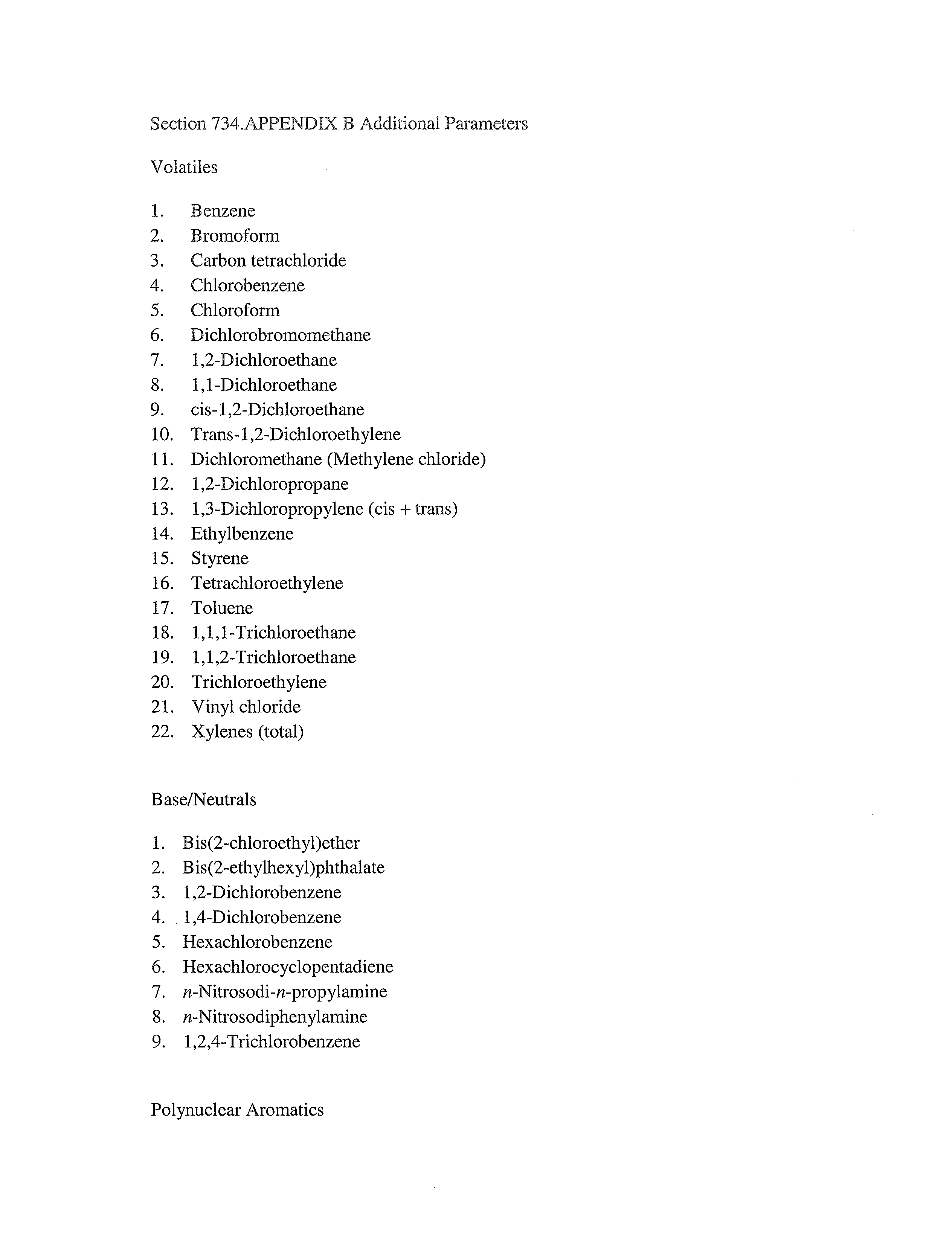

Chart 3

Individual, 104, 20%

Businesses, 354, 67%

Government, 11, 2%

Community, 25, 5%

Church, 7, 1%

School, 29, 5%

Note:

Chart 3 quantifies various characteristics of the PRP

1 group. To prepare Chart 3 we utilized a random

number generator program to select approximately

10% of the PRP 1 group. We then separated the

final list of approximately 530 PRPs into the

categories of individuals, churches, government,

schools, municipalities and businesses using

naming conventions. After the initial categorization

PRP we performed an additional analysis of the

business and community categories using

demographic and other information obtained ESRI

Business Analyst and InfoUSA, a nationally

recognized consumer/business database. We also

compared this list to the Illinois Petroleum Marketers

(IPMA) 2005 membership list. During this process

we discovered numerous data gaps (e.g., lack of

addresses, companies out of business, duplicate

names) so the data should be considered

approximate rather than absolute. However, the

data patterns were more than sufficient to

understand the basic trends and characteristics

outlined in this testimony.

PRP 1 Characteristics

Page 19 of 49

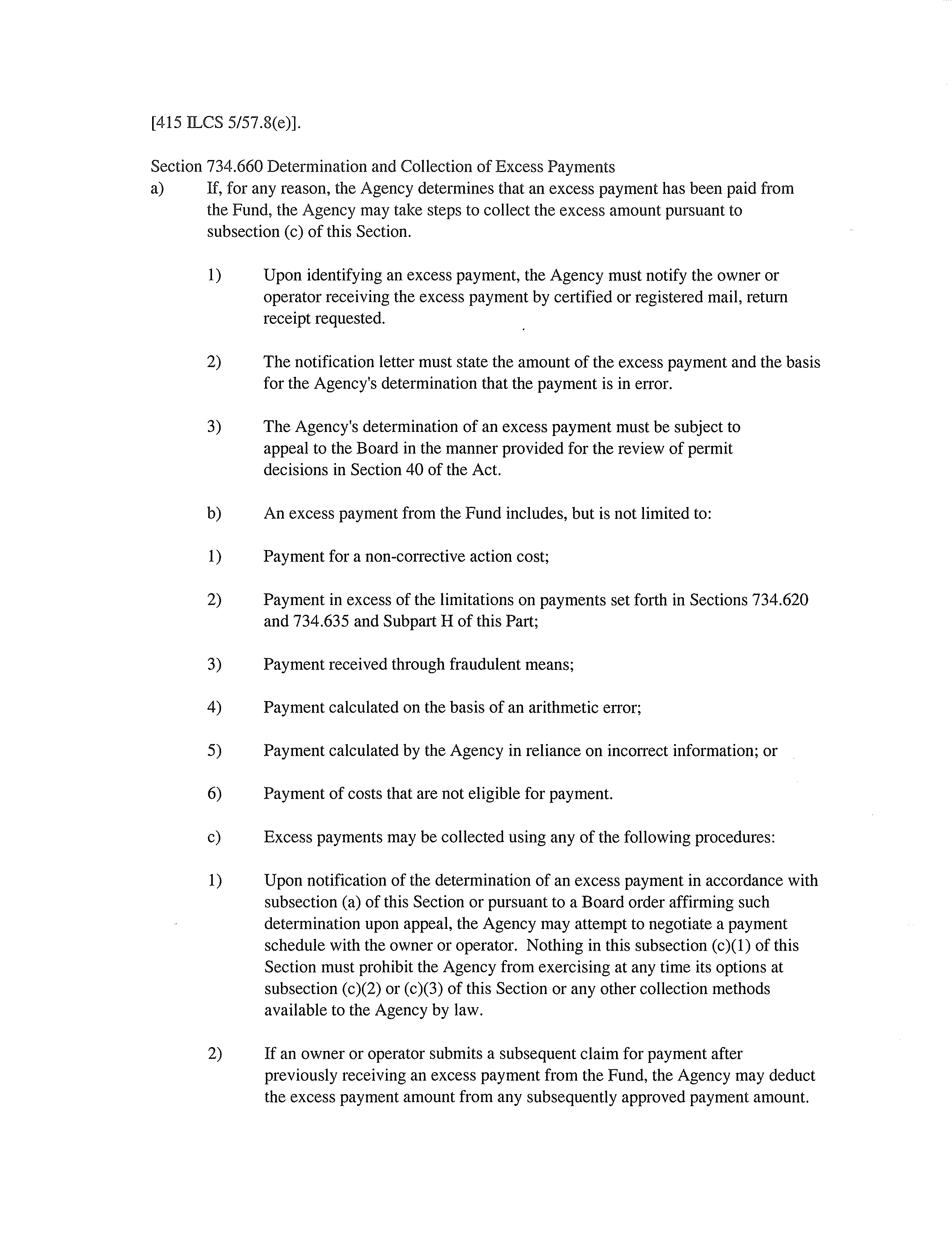

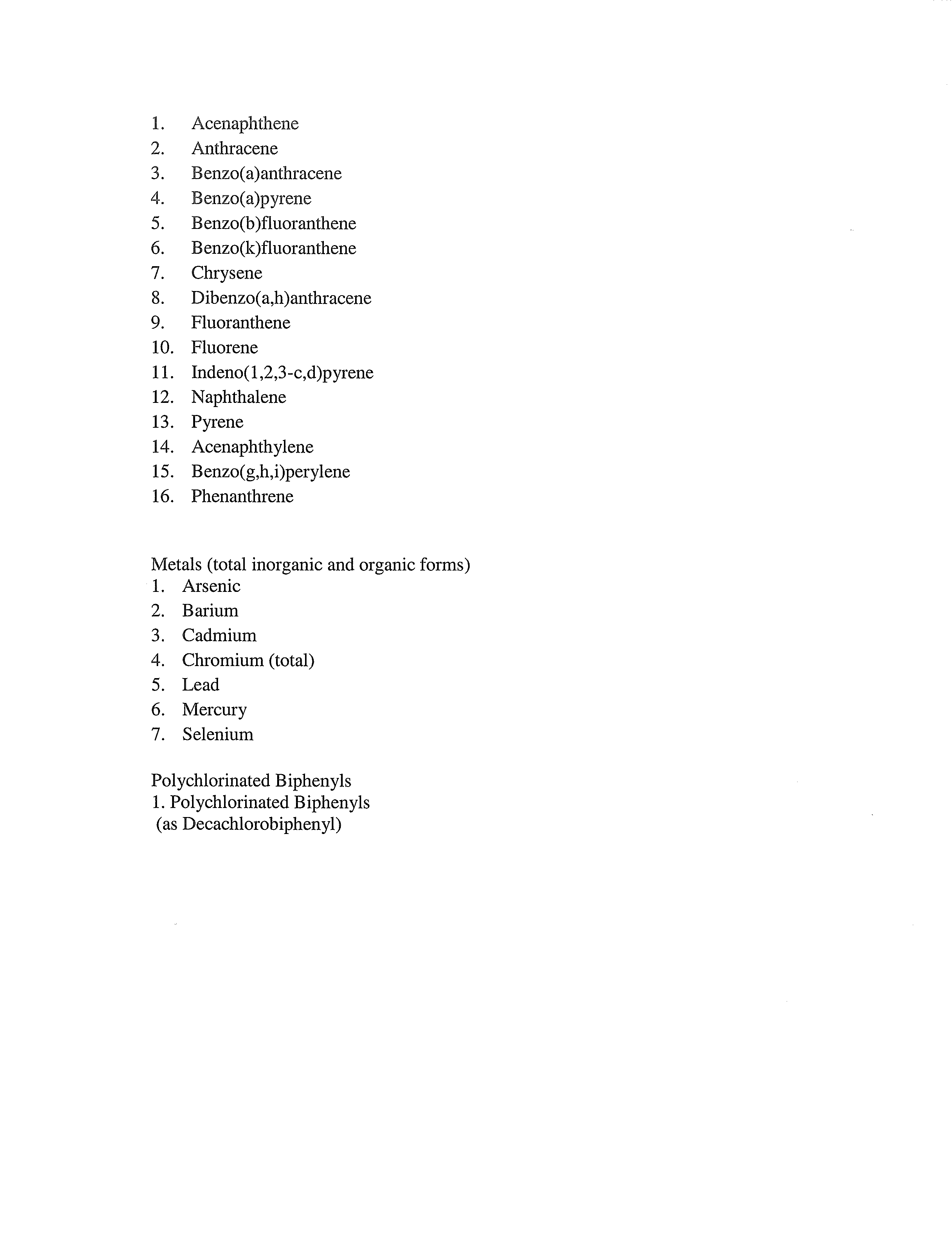

Chart 4

Businesses, 38, 74%

Government, 12, 24%

Community, 1, 2%

Note:

Total number

of PRP 21 is

51.

PRP 21 Characteristics

Note:

Chart 4 was prepared

in a similar fashion to

Chart 3.

Page 20 of 49

Section 2-

Review of Reasons for this Rulemaking

Background Information

:

Unlike the technical aspects of their proposal, the Subpart H portion of the

proposed rules were developed by the Agency, not as the result of a legislative mandate,

but rather through the Agency’s motivation to create rules. Although the Agency has

stated a number of reasons behind the Subpart H portion of the proposed rule, several

participants in this process have publicly questioned and privately commented about the

real motives of the Illinois EPA relating to Subpart H.

The Agency has publicly stated that the “most notable” reason behind their

proposal is a need to reform the budgeting and reimbursement procedures. (Opinion and

Order; page 15, page 22, and, page 24, ). The Agency’s statement begs two questions:

1. What is driving this need?; and, 2.) What types of reforms are needed?

The Agency

has sold the Board on the concept that these reforms are needed:

1.) So that the Agency can “streamline the preparation and review of budgets and

applications for payment”. (Opinion and Order; page 15, reference to testimony of Doug

Clay);

2.) To make the program more cost effective (Opinion and Order: page 26,

reference to testimony of Gary King);

3.) To reduce the amount of time spent by Agency personnel on the review of

budget and reimbursement issues (Opinion and Order; page 26, reference to testimony of

Gary King);

4.) To improve consistency in Agency decisions; (Opinion and Order; page 17,

reference to testimony of Doug Clay);

Page 21 of 49

5.) To control clean-up expenses (Opinion and Order; page 17, reference to

testimony of Doug Clay);

6.) To expedite clean-ups; (Opinion and Order; page 17, reference to testimony of

Doug Clay)

7.) To reimburse owners/operators in a more timely and efficient fashion.

(Opinion and Order; page 17, reference to testimony of Doug Clay);

8.) To reduce the amount of time that will be needed for consultants to prepare

budgets and payment applications. (Opinion and Order; page 17, reference to testimony

of Doug Clay) and;

9.) To reduce the level of incidence of what the Agency believes are “abuses of

the system”. (Opinion and Order page 26, reference to testimony of Gary King)

On the surface, the reasons for reform stated by the Agency seem reasonable.

Taking each of their declared motives at face value, and assuming that they are genuine

in their desire to achieve their above stated goals, one would easily surmise that the

Agency would be open to suggestions that were consistent with their stated goals. Of the

items stated above, items 1, 3, 5, 6, 7 and 8 all have to do with the goal of either

streamlining, creating efficiency, expediting or reducing processing time. Actions speak

much louder than words. The genuineness of the Agency’s stated motives listed above

are called into question when one considers the numerous proposals that have been made

by the parties in this proceeding to reduce processing times and streamline processes.

The Agency’s response to these various proposals has always been consistent. In each

instance they have rejected the proposal. Specific examples of such instances include:

Page 22 of 49

1.

The Agency’s rejection of the proposal by PIPE that a database needs

to be developed to assure accuracy in the maximum payment amounts

(Opinion and Order; page 69);

2.

The Agency’s rejection of the suggestion by PIPE of a reduction in the

amount of time allowed for reviews of plans and budgets to less than

120 days (Opinion and Order; page 69) (please note that in this instance

the Agency suggested that any such changes would have to be statutory

in nature. However, the applicable statute only sets forth the maximum

timeframe that the Agency has to perform such reviews. If the Agency

was genuine in its desires to “streamline” and “expedite” the process

nothing in the statute would prohibit the Agency from decreasing its

internal timeframes for review);

3.

The proposal by PIPE of a “draft denial letter” to be entered (Opinion

and Order; page 69) into the Agency’s process in order to help resolve

disputes before such disputes must go to the Board on appeal;

4.

Anyone with knowledge or experience in the process of bid

specification preparation, bid solicitation, contract management and

administration, knows that the Agency’s introduction, in the third

errata

sheet, of a competitive bidding process into their program will

add levels of complexity and administration that will certainly not

permit for the “streamlining” or “expediting” of the LUST program that

they have declared they desire;

Page 23 of 49

5.

Finally, the blasé approach that the Agency used in the development of

many of the rates proposed in Subpart H, is not indicative of a party

truly interested in streamlining and efficiencies. The LUST section is a

scientifically oriented organization consisting of scientists and

engineers.

Scientists and engineers are trained to hypothesize, test,

study, analyze, plan and design and are typically motivated more by

getting things right than merely “throwing something together”. It is

highly suspect that a group trained in these disciplines would use such a

nonchalant approach if their interest were truly genuine. Please see

Attachment 2 for a list of all those that testified that a scope of work

was needed for each maximum payment amount.

One can hardly conclude from the record, that the Agency’s motives are to

streamline, create efficiencies, expedite, or reduce processing times.

Item two above provides that one of the Agency’s stated motives for this

rulemaking is “to make the program more cost effective”. When questioned as to the

level of cost savings that are likely to be achieved if this proposal is implemented, the

Agency admitted that it had not performed an analysis of the anticipated cost savings.

(Opinion and Order; page 17, referencing testimony of Doug Clay). It seems reasonable

that if one has a genuine desire to cut costs, if for no other reason than to satisfy one’s

own curiosity with regard to their contemplated actions, one would want to analyze and

forecast the cost savings that might be generated. It also seems reasonable that if one was

genuinely concerned about cost reduction, it would want to be in a position to properly

defend its proposals. The Agency’s failure to predict the cost savings of their proposal

Page 24 of 49

calls into question whether they genuinely want to achieve that goal or whether there is

some other motive behind their proposal.

While, the Agency’s failure to analyze the costs savings of this proposal

calls into question whether cost reduction is the true objective, the Agency’s outright

rejection of the request by PIPE, the ad hoc group, and nearly every consultant that

testified in this proceeding, to define a scope of work, when taken in the context of the

competitive bidding process proposed by the Agency in the third

errata

sheet, is an

absolute formula for financial disaster for the LUST program. Anyone with any business

savvy whatsoever, understands that increasing levels of risks will serve to increase the

costs of products and services. For instance, the state of Illinois is currently involved in

a serious medical malpractice crisis. The costs for physicians doing business in Illinois to

obtain medical malpractice insurance is significantly higher than in many other states.

This is due to the increased risks of lawsuits in Illinois. It is only logical to believe that

the Illinois EPA’s refusal to define a scope of work for each maximum payment amount

increases the level of uncertainty and risks and will drive bid prices higher. As a result

the total costs to the fund will escalate and the Agency will have no choice but to pay the

higher prices because their own regulation will require them to do so. Additionally, the

fact that the Agency has refused to standardized a scope of work means that each

consultant that prepares a bid specification will do so uniquely, thereby increasing the

Agency’s cost of review. The Agency’s refusal to define a scope of work for each

maximum payment amount along with their proposal to add a competitive bidding

process to establish alternatives to maximum payment amounts for which they have

Page 25 of 49

refused to define a scope of work is not only inconsistent with their stated goal of making

their program more cost-effective, it is actually counter-productive to that goal.

Similarly, the Agency’s refusal to define a scope does not even scarcely support

their stated goal of “improving consistency in their decisions” as they have alleged is a

goal in item number four above. Imagine how “straightforward” it will be for an agency

reviewer to evaluate and compare a competitive bid price obtained pursuant to a “scope

of work” prepared by a consultant in a competitive bid specification to a maximum

payment amount that has no defined scope of work. The only consistency in a system so

poorly designed will be consistent chaos and consistent appeal. As long as the Agency

maintains that a defined scope of work is not needed for each task for which there is a

maximum payment amount they cannot claim that they desire more consistency in their

decisions.

With the above stated motives in this rulemaking being refuted, one is left to

consider the Agency’s stated concern about alleged increases in the incidence of

perceived abuses of the system. This comment, included in Gary King’s testimony pg

26, is almost akin to a distress signal, and is a baffling comment to be made by a senior

level manager of the very organization that, pursuant to statute, has been granted not only

the authority but also the responsibility to oversee the UST program and determine the

reasonableness of reimbursement (Opinion and Order; page 20) and more specifically the

responsibility to review all submittals for consistency with the Act and Board regulations.

(Opinion and Order; page 68). Considering the fact that the program requires pre-

approvals of budgets and work plans before reimbursement claims may be processed, and

the fact that the Agency has already been granted the broad authority by the Illinois

Page 26 of 49

legislature to audit all data, reports, plans, documents and budgets submitted to the

Agency (Opinion and Order; page 66), it is almost impossible to conclude that the

Agency does not already have the ability to thwart any abuses that might be perpetrated

against the system. This conclusion is crystallized in view of Gary King’s March 15,

2004 testimony that states that the Agency has never been accused of operating a give-

away-program” and that the Agency is constantly aware that the Agency is responsible

for reimbursing the “reasonable costs” of remediation. (Opinion and Order; page 26).

Finally, the Agency’s argument in response to PIPE’s proposal to rely upon the

certification of a number of licensed professional engineers or geologists makes the

Agency’s power and authority in making decisions related to LUST reimbursements

quite clear. In that argument, the Agency stated that neither Section 57.7 of the Act (415

ILCS 5/57.7(2002)) or the regulations are intended to grant licensed professional

engineers or geologist with a final decision making authority that supercedes the Agency.

The Board concurred with the Agency’s position on this matter and so does USI.

(Opinion and Order; page 68)

Because of the Agency’s actions and testimony during this proceeding, it is

difficult if not impossible to rationalize any of the motives that the Agency declared when

they first proposed Subpart H in early 2004.

One additional motive that was stated by the Agency during the proceedings is

that the LUST Fund is operating at a deficit of approximately $25 million per year and

that if this difference is not reduced delays in payment could occur. (Opinion and Order;

page 17). All parties in this proceeding know that in recent years the LUST Fund has

been the subject of statutory transfers to other programs so this testimony should not be

Page 27 of 49

weighted too heavily.

Additionally, if a true funding crisis actually exist, why has the

Agency not notified owners/operators pursuant to 732.503(h) and 734.505(g)?

In addition to the IEPA’s declared motives, there are a number of other motives

that have been discussed within industry circles during the course of the past year and

one half. One is that the IEPA has been asked to reduce expenses so LUST Fund monies

can be siphoned off to other state programs as a result of the fiscal problems that the state

has been experiencing in other programs. One is that the regulators view the LUST

Fund as their “cash cow” and want to protect balances in the Fund to protect their own

jobs. One is that a current IEPA employee who is a former competitor to Illinois LUST

consultants is driving these changes as means of settling a vendetta against his former

competitors. Another is that the Agency is adamantly opposed to the business practices

of some consultants that “defer payment” for their services until such time that their

clients are reimbursed and/or guaranteed that their services will be reimbursable and that

the Agency wants to use this rule as a means to diminish them.

The real motives are

never likely to be stated publicly but whatever the true motive, the Agency needs to keep

the needs of the small owner/operator at the forefront.

Section 3. Historical Administration of the Illinois LUST Program

.

In the Board’s Opinion and Order the Board states “Although the Agency’s

methodology for determining the maximum rates is not statistically defensible, the

Agency’s data is from actual applications for reimbursement for sites in Illinois. The

Agency’s testimony is that the rates as developed will be inclusive of ninety percent of

the sites remediated in Illinois (see Tr.3 at 54-56). Therefore, the Board finds that the

Page 28 of 49

Agency’s method for developing the maximum payment amounts is primarily based on

the Agency’s experience in administering the UST program in Illinois. The Board further

finds that the rates are reasonable. Any deficiencies in the maximum rates are obviated

by the language dealing with extraordinary circumstances and the addition of the bidding

process.” (Opinion and Order; page 79)

In the immediately preceding paragraph the Board states, “The participants

questioned the Agency extensively on the procedures used to develop the rates. The

comments and testimony before the Board demonstrated real concerns with how the rates

were developed. However, other than certain specific areas, alternative rates were not

offered.” (Opinion and Order; page 78).

A close examination of the Board’s language on these two pages, and elsewhere

within the Opinion and Order, leaves little doubt that, in the absence of a competitive

bidding process (734.855) and the unusual and extraordinary circumstances provisions

(734.860), the Board would have been extremely hesitant and probably unwilling to

accept the maximum payment amounts proposed by the Agency in Section 734.810

through 734.850. The likelihood that the maximum payment amounts proposed by the

Agency are insufficient is clearly on the board’s mind when they state that “Any

deficiencies in the maximum rates are obviated by the language dealing with

extraordinary circumstances and the addition of the bidding process”.

The Board’s

language explaining why the Board changed the payment unit of measure for the task of

preparing competitive bid specifications from “lump sum” to “time and materials” is

understandably to address the Board’s concern that the maximum payment amounts may

be too low. In that portion of the Opinion and Order the Board states that “The Board is

Page 29 of 49

especially concerned given that bidding is an alternative to any of the lump sum

payments in Subpart H and the Board is not convinced that the maximum rate of $160

would be sufficient for the preparation of a request for bids and review of bids for all of

the tasks in Subpart H.” In this passage, the Board indirectly acknowledges the potential

insufficiency of the maximum payment amounts proposed in Sections 734.810 through

734.850 by helping to assure the sanctity of the alternative means of establishing

maximum payment amounts. Perhaps even more importantly in this instance, the Board

disqualifies, as insufficient, the maximum payment amount for the preparation of bid

request and review of bids. Interestingly enough, when utilizing the approach that the

Board elected to publish at First Notice, which is the use of competitive bidding and the

extraordinary circumstances provision as an alternate means of establishing maximum

payment amounts, the only truly critical rate in the entire structure is the rate associated

with bid preparation and review. The fact that the Board chose to disqualify the

Agency’s proposed rate for those activities speaks volumes.

The Board’s statement on page 78 (Opinion and Order) indicates that the Board

would have been willing to consider alternative rates if they were presented. As a point

of clarification, it is important to note that USI and other PIPE members were cautioned

prior to the 2004 hearings to not discuss rates amongst one another for legal reasons. As

a result, PIPE and its members refrained from providing alternative rates. In order to

avoid these legal issues other solutions, such as RS Means, were offered by PIPE.

USI agrees with the Board when they state that the rates should be based upon

actual experience in the UST program in Illinois. (Opinion and Order; page 79). RS

Means and other sources that do not specifically track costs associated with the Illinois

Page 30 of 49

UST program are not likely to reflect the requirements and costs unique to the Illinois

Leaking Underground Storage Tank Program.

The Agency has testified that they have developed the rates from their experience

in administering the LUST program in Illinois and that they believe that the rates that

they have presented will be inclusive of ninety percent of the sites in Illinois. (Opinion

and Order; page 79) Given the methods that the Agency used to develop the rates and

USI’s experience in UST work in Illinois which includes extensive experience in both

consulting and contracting work, USI is not-objectionable to most of the maximum

payment amounts provided in Section 734.810 through 734.840. Please see Section 4 of

this testimony for additional discussion of this topic.

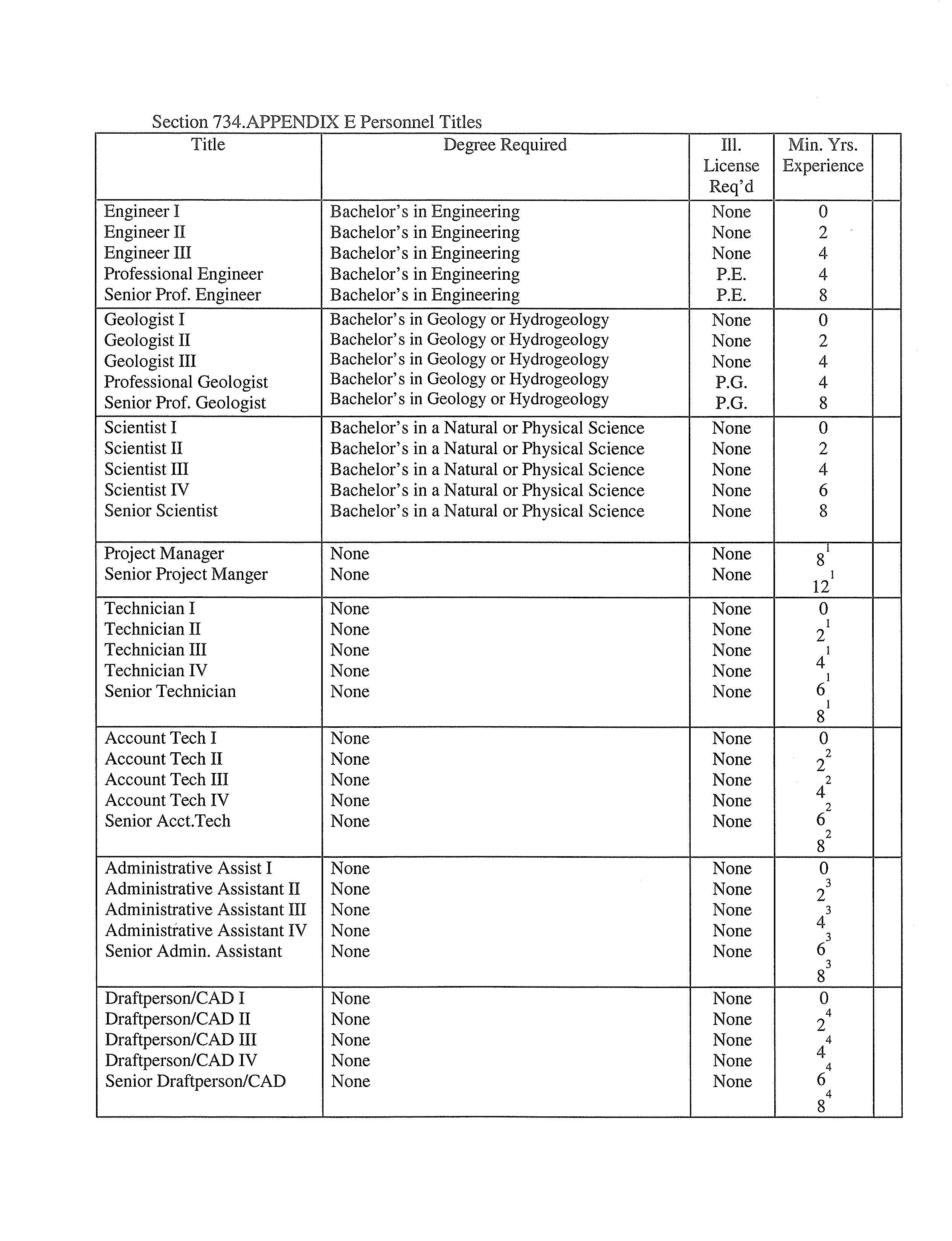

However, USI is confident that the record is significantly in error as it pertains to

the consistency of the maximum payment amounts provided in Section 734.845

compared to the Agency’s historical and current reimbursement practices. USI that other

than with regard to the labor rates provided in Appendix E, the Agency’s experience in

administering the UST program is of little use. This statement will be explained in more

detail later.

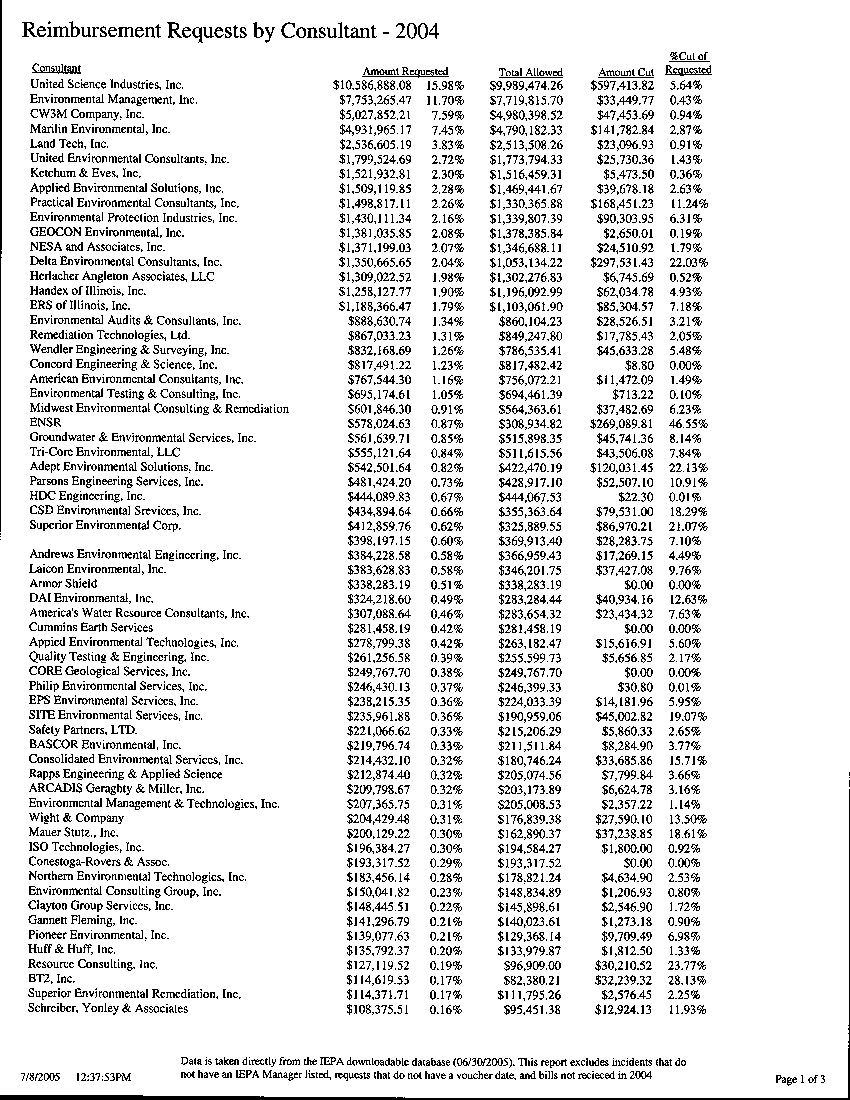

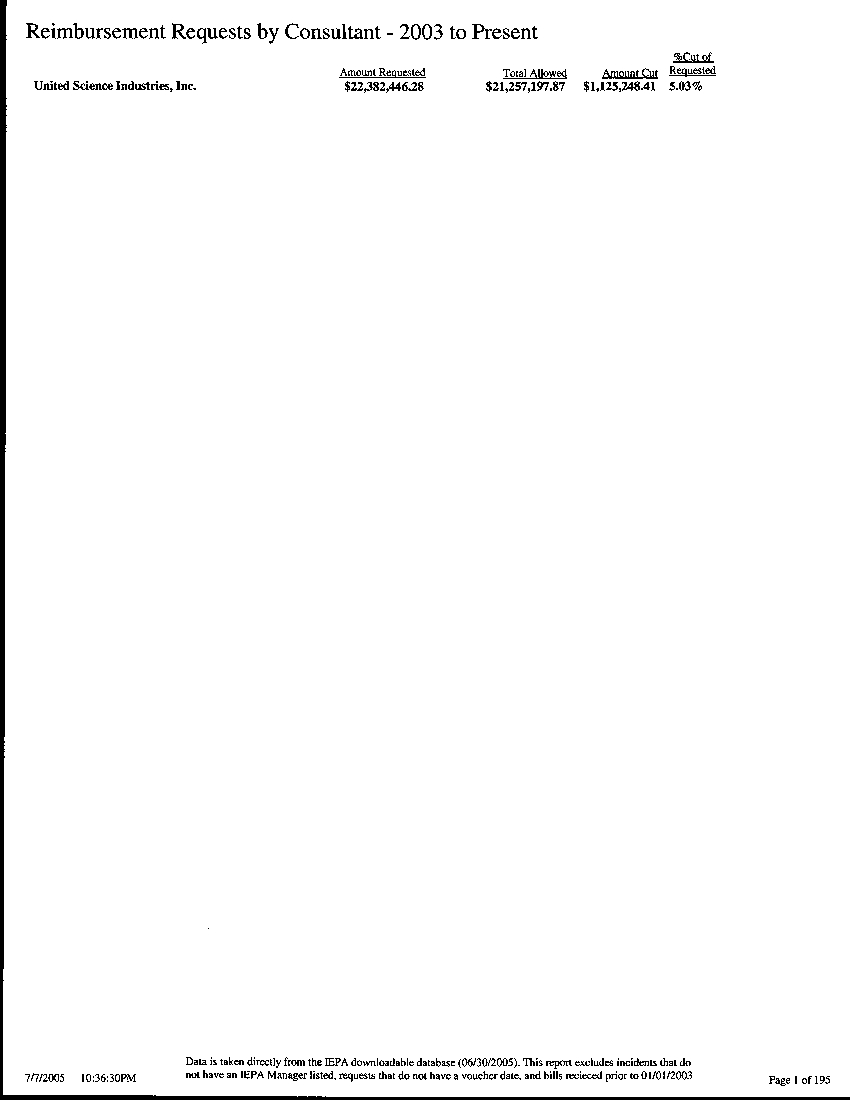

USI’s experience in dealing with the UST program is significant. In each of

2003 and 2004, on behalf of our clients, USI submitted over fourteen percent of all

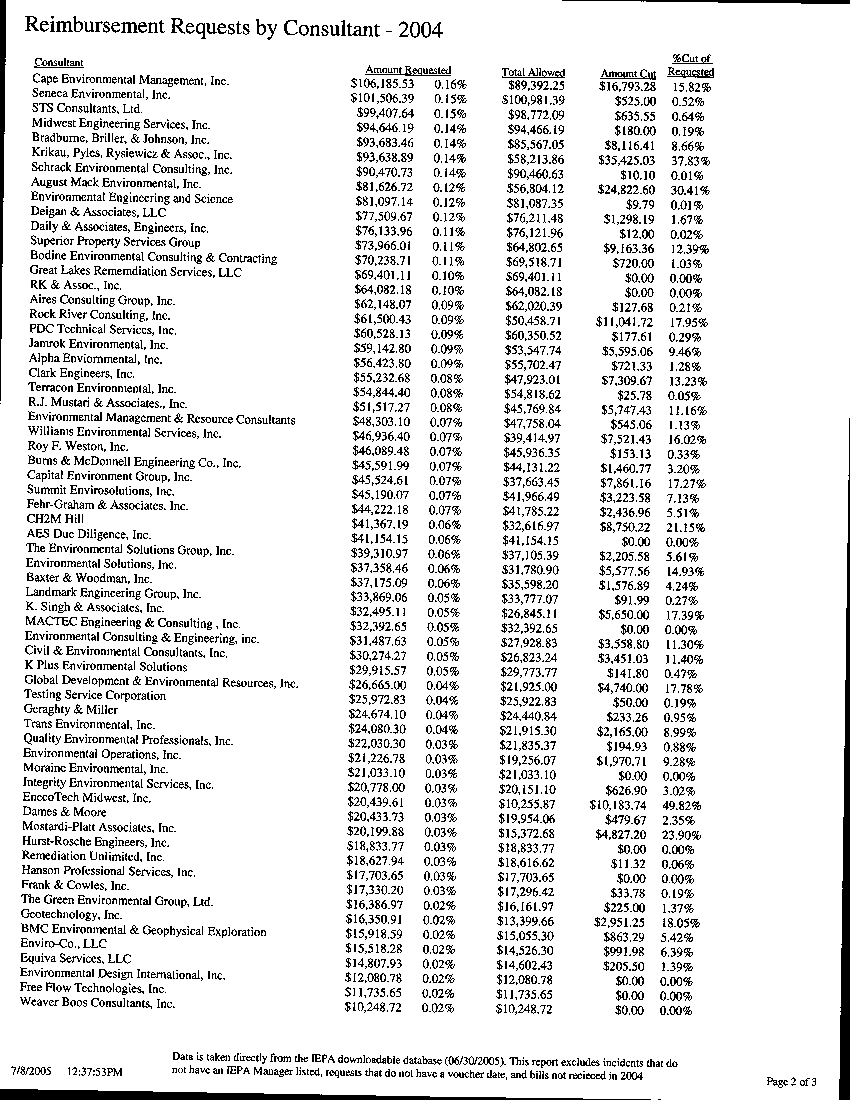

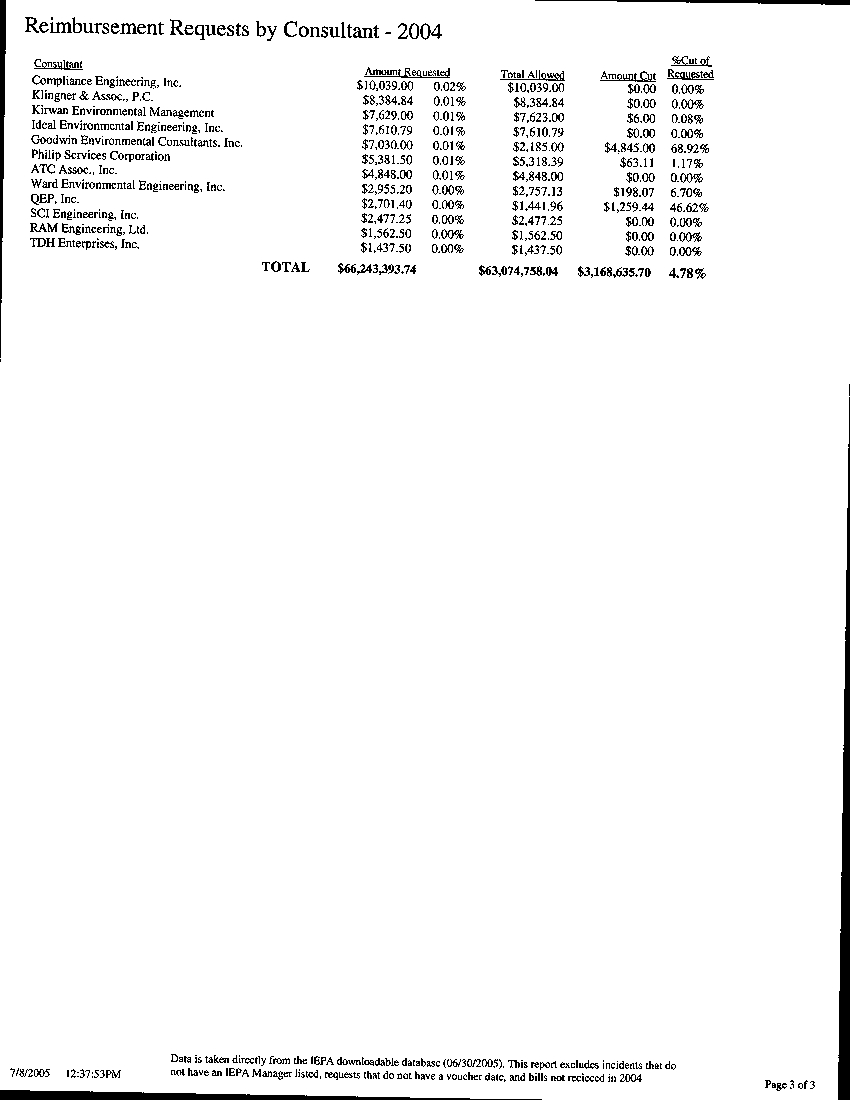

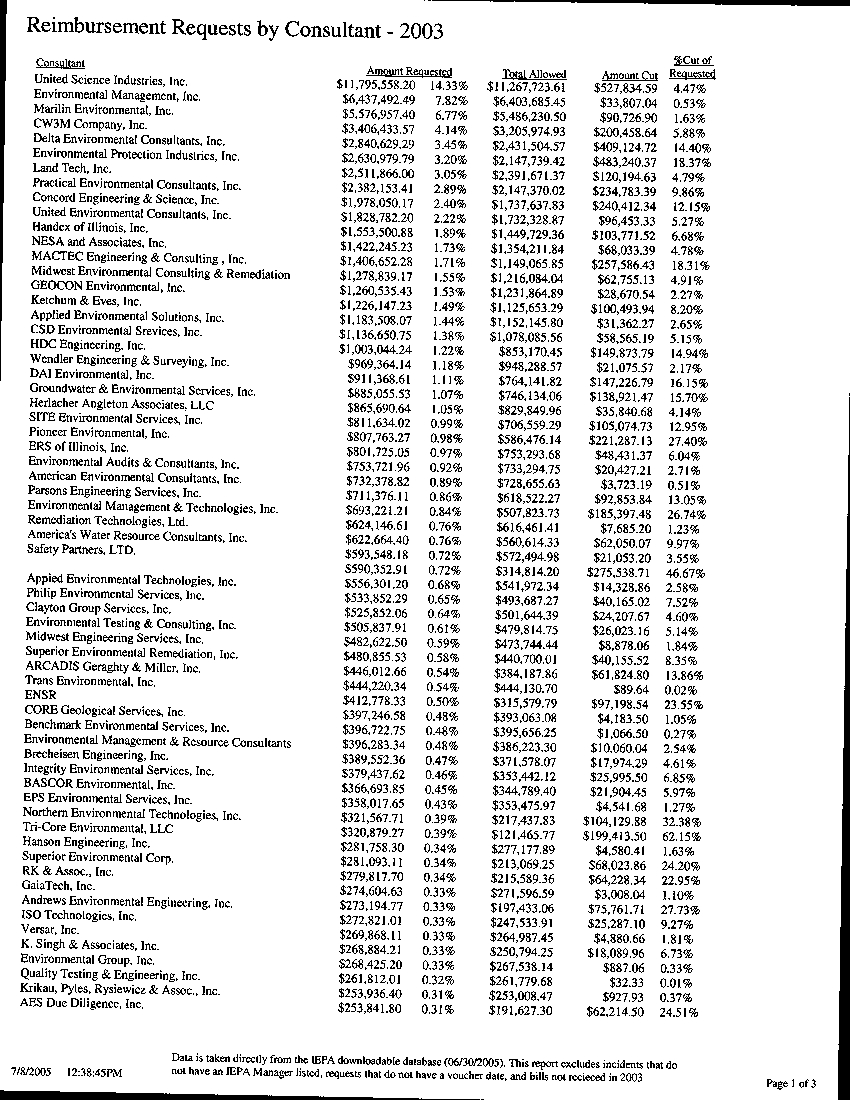

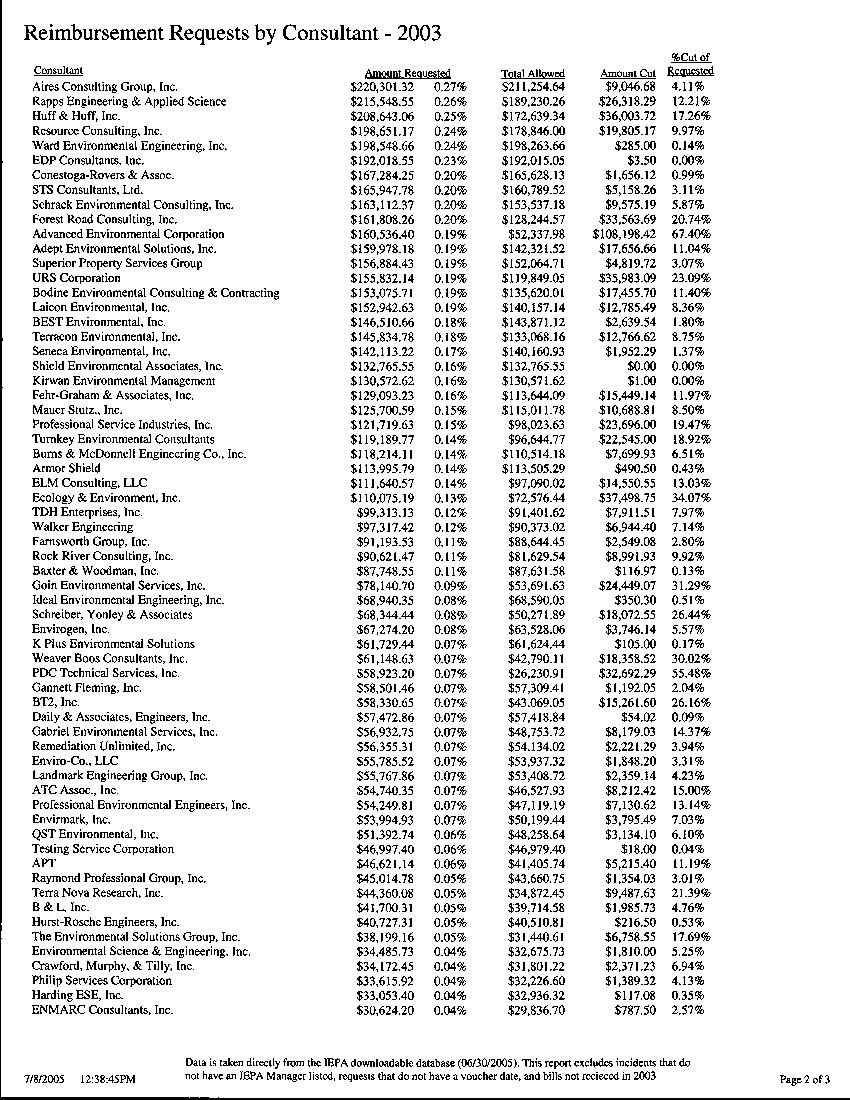

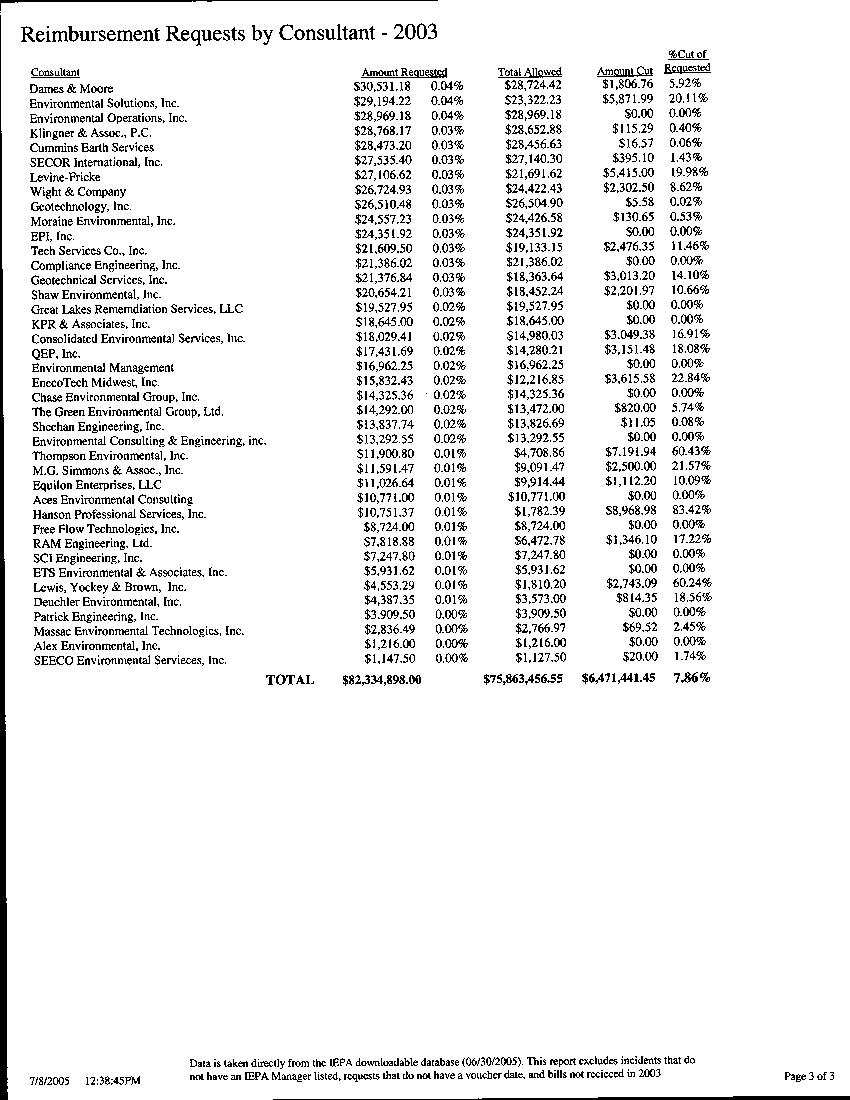

reimbursement claims submitted to the UST program. (see Attachment 3)

.

Our

historical reimbursement percentage is well above the sate-wide average. (see

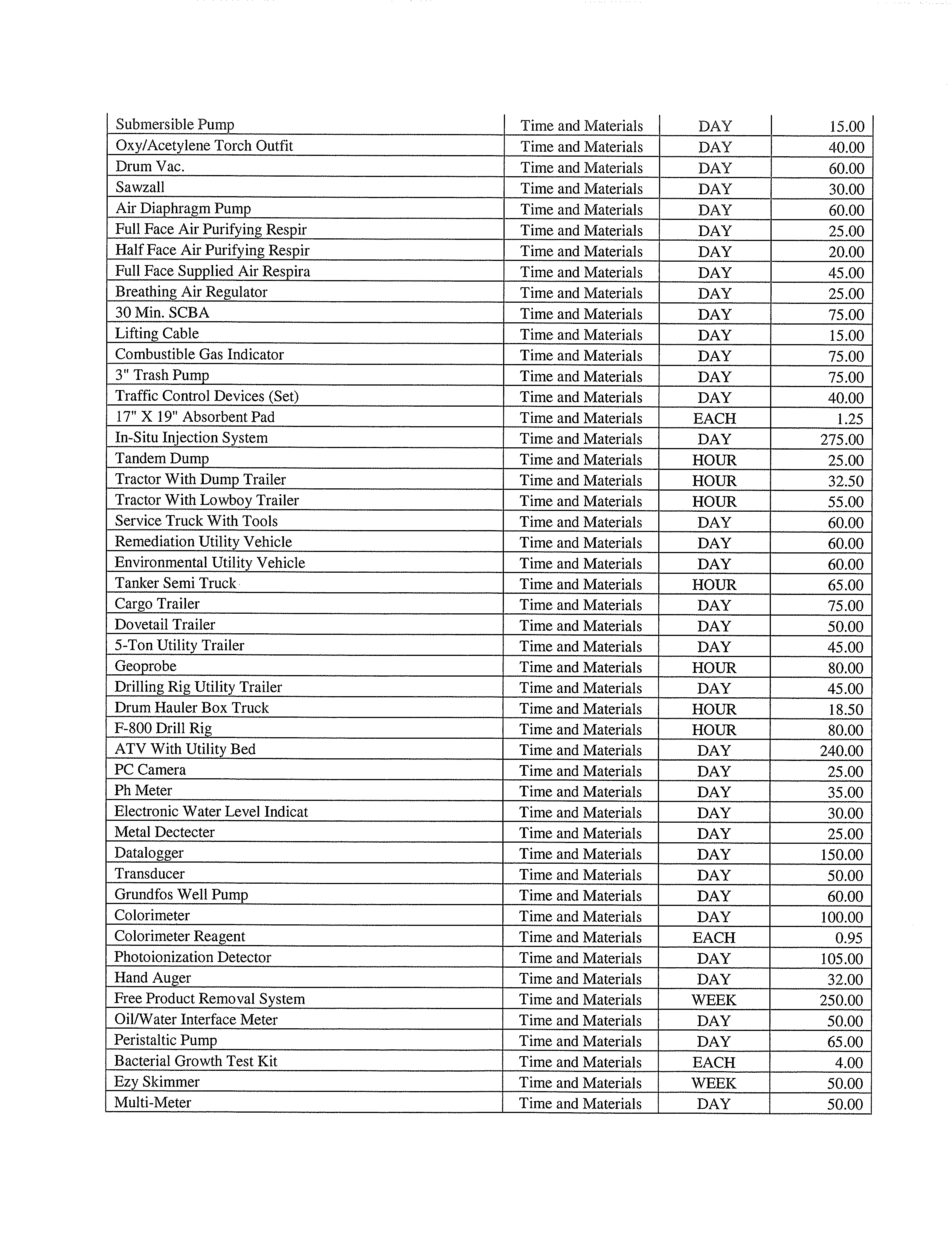

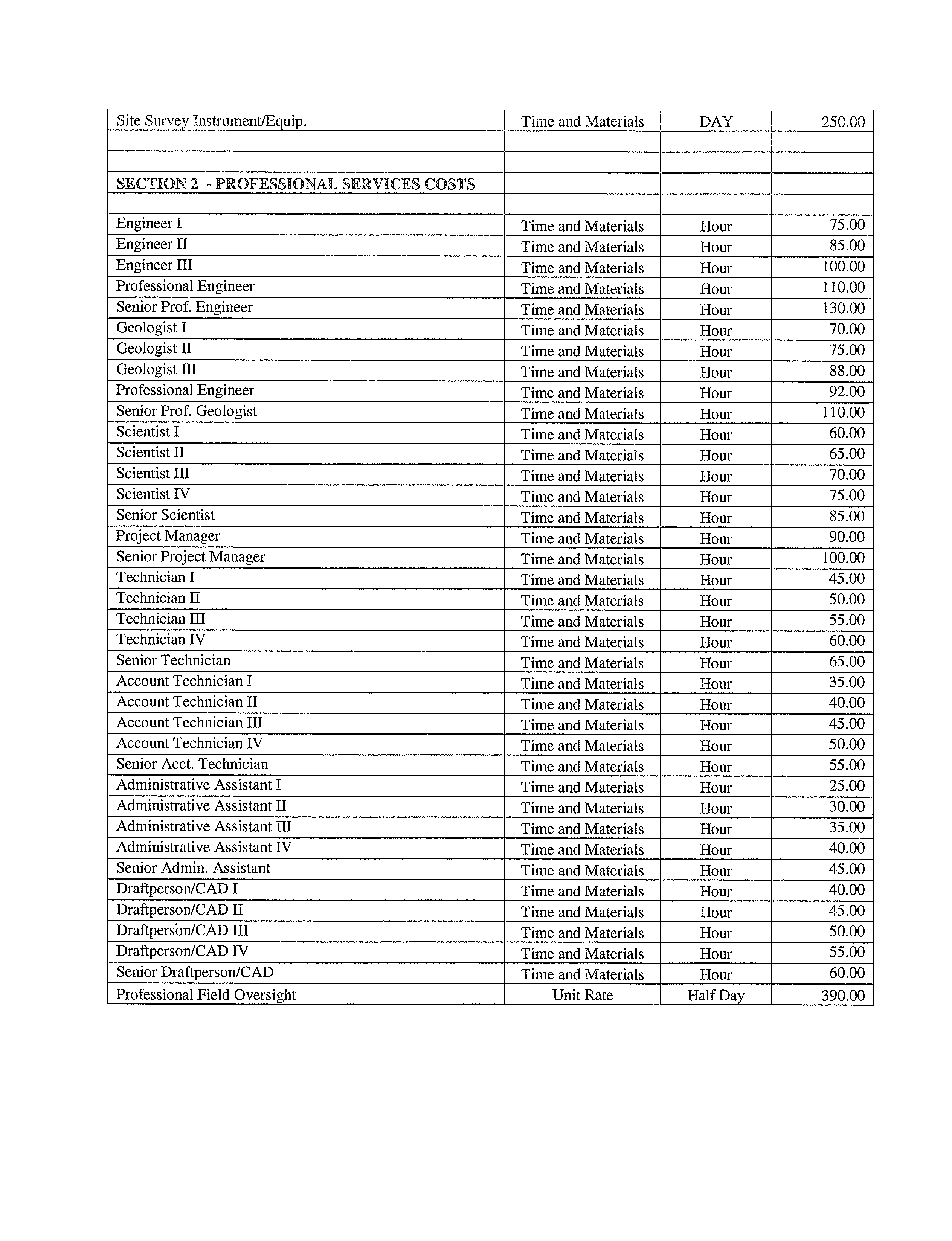

Attachment 4) USI’s fee schedule items are routinely and consistently approved by the

Agency in budget proposals and reimbursement requests and they have been for years

based on our own experience at the sites we represent. USI has observed numerous

Page 31 of 49

examples where the Agency’s proposed maximum payment amounts deviate from the

rates that the Agency currently and historically considers to be reasonable. USI submits

its fee schedule as Attachment 5. This fee schedule provides rates that are currently

being reimbursed in Illinois for professional services. USI would like to emphasize that

this fee schedule provides charges for professional instrumentation, equipment and

materials and supplies that the Agency has omitted from Subpart H. In light of the fact

that numerous professional service oriented time and materials tasks are provided in

Subpart H, and the fact that instrumentation, equipment and materials and supplies are

resources that are just as critical and necessary to the completion of a corrective action as

is professional labor, it would only be wise to include in Subpart H, time and materials

maximum payment amounts for the instrumentation, equipment and materials and

supplies that are routinely used by professionals.

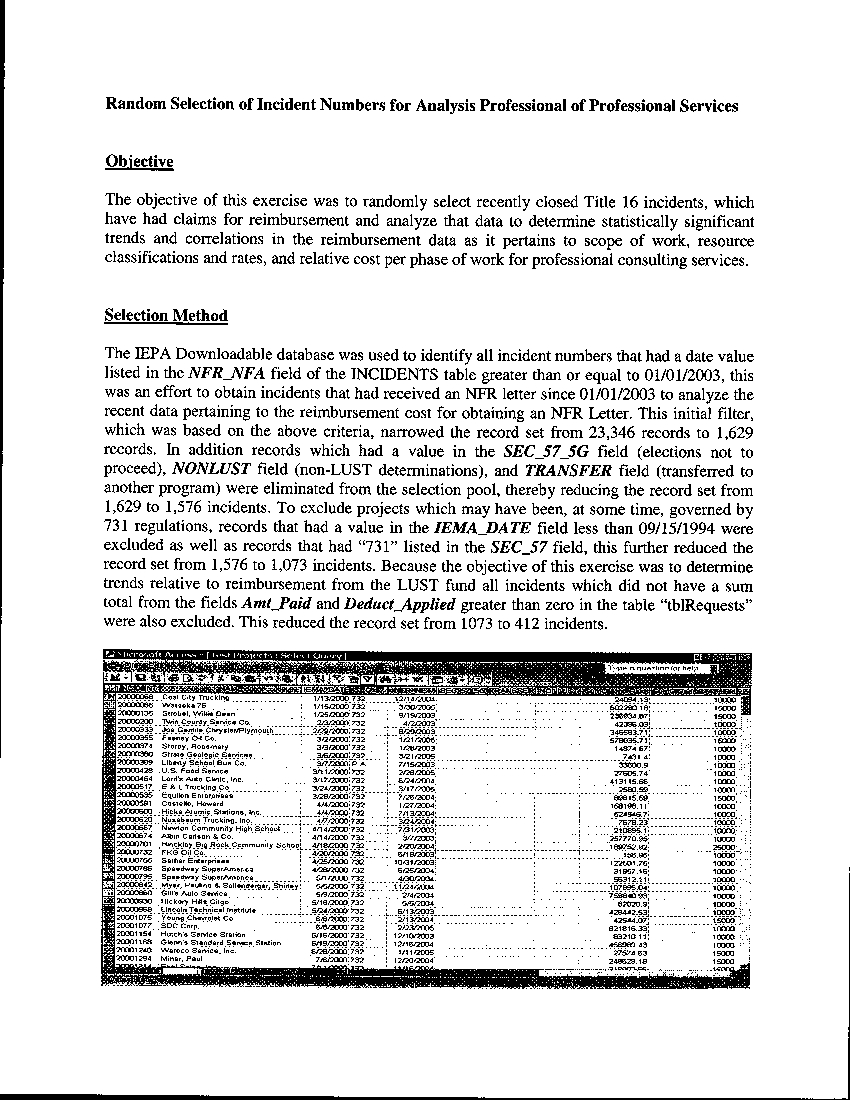

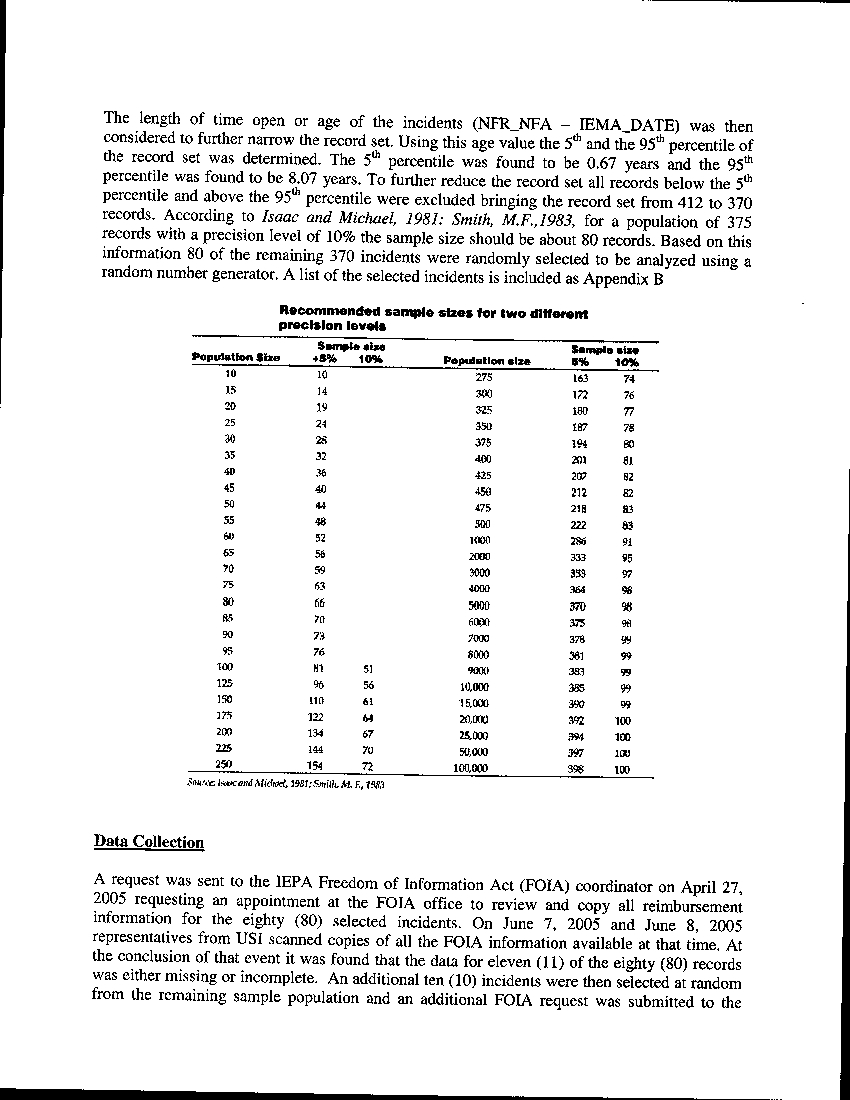

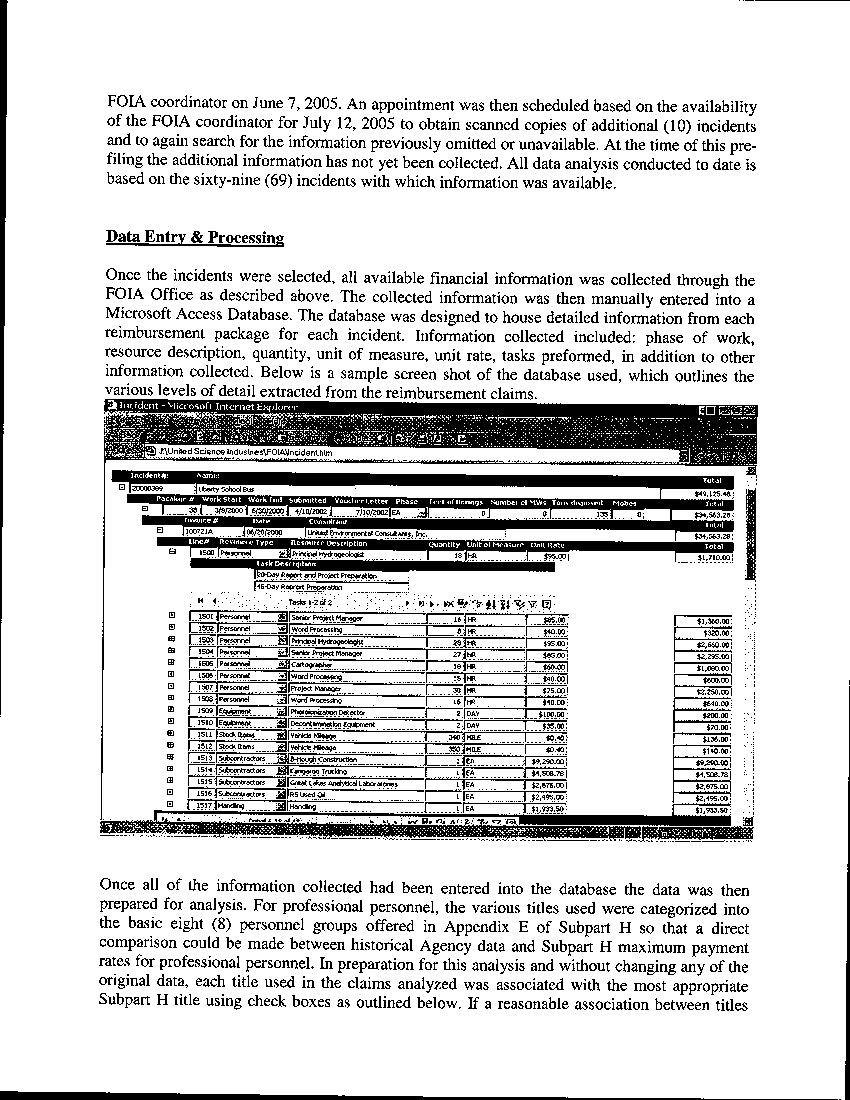

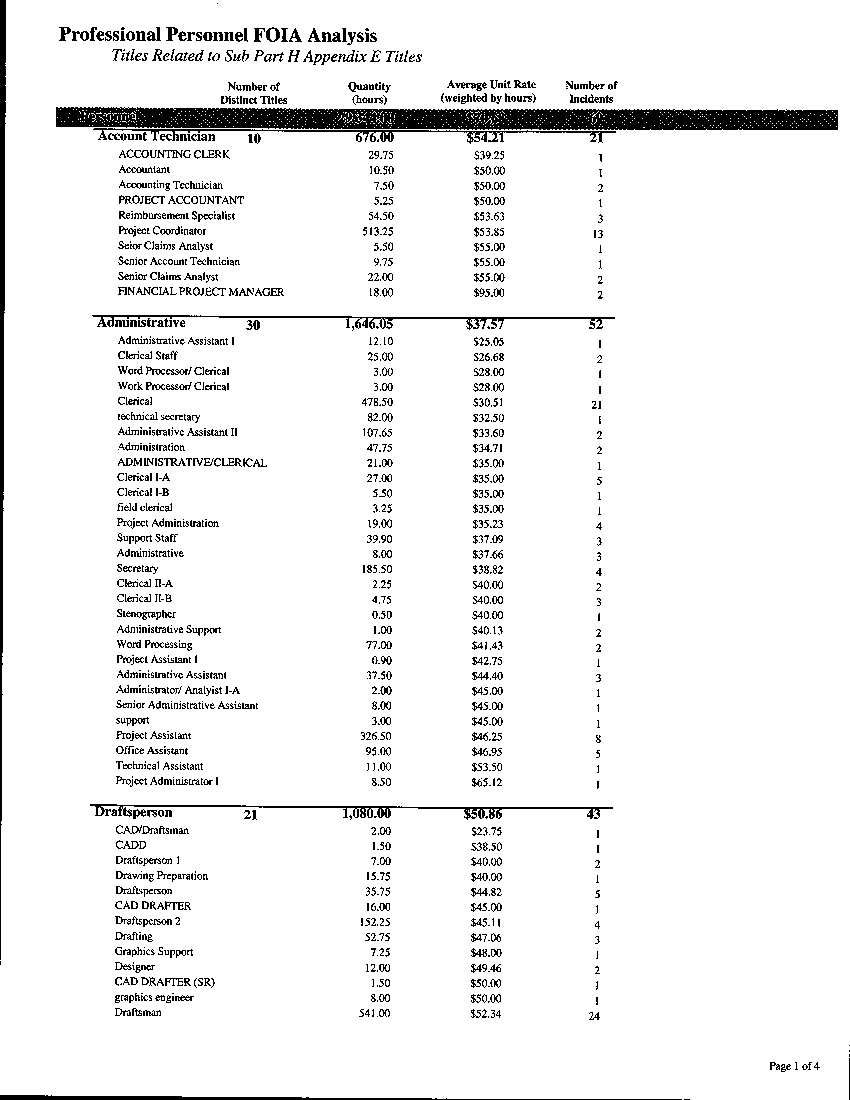

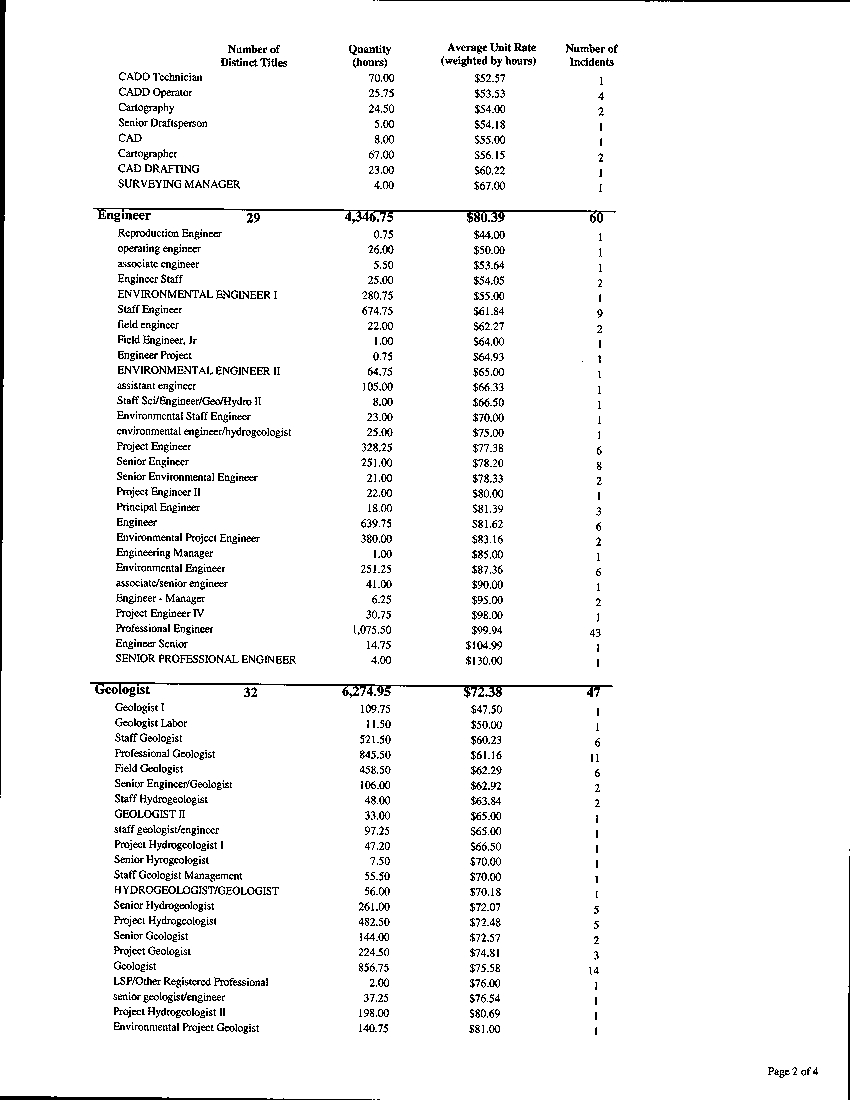

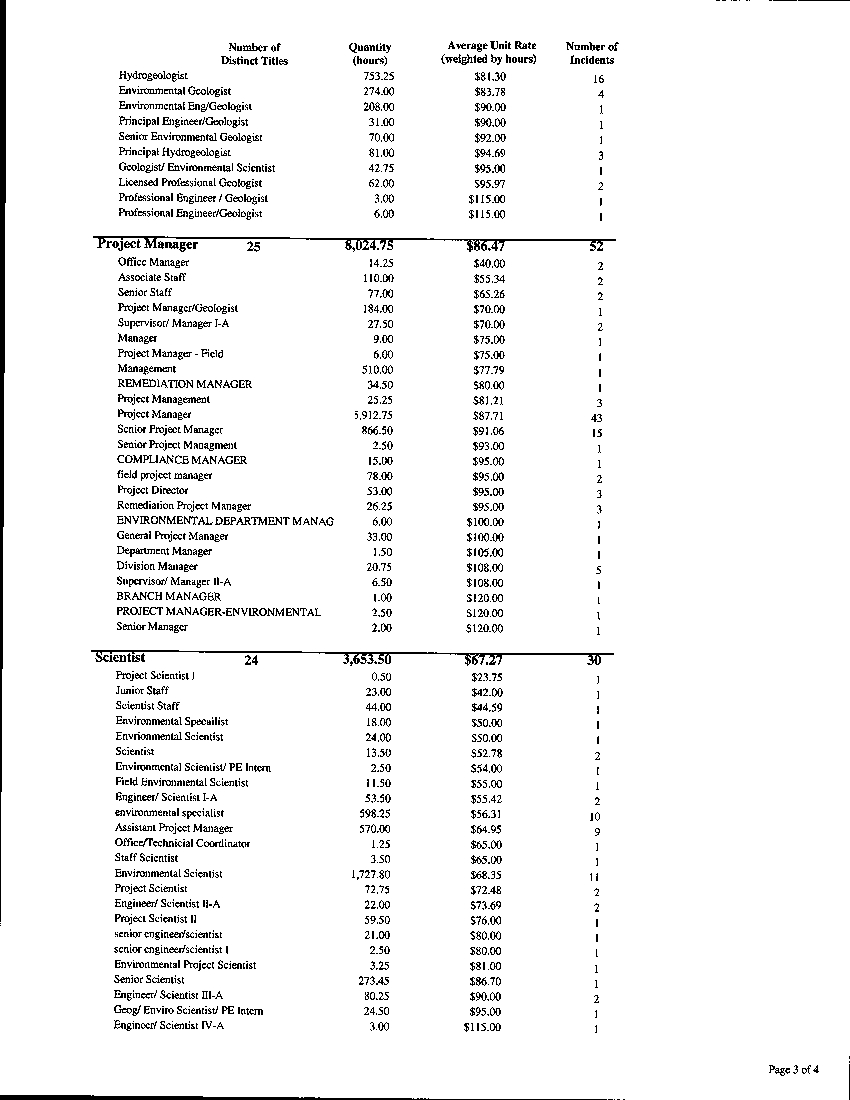

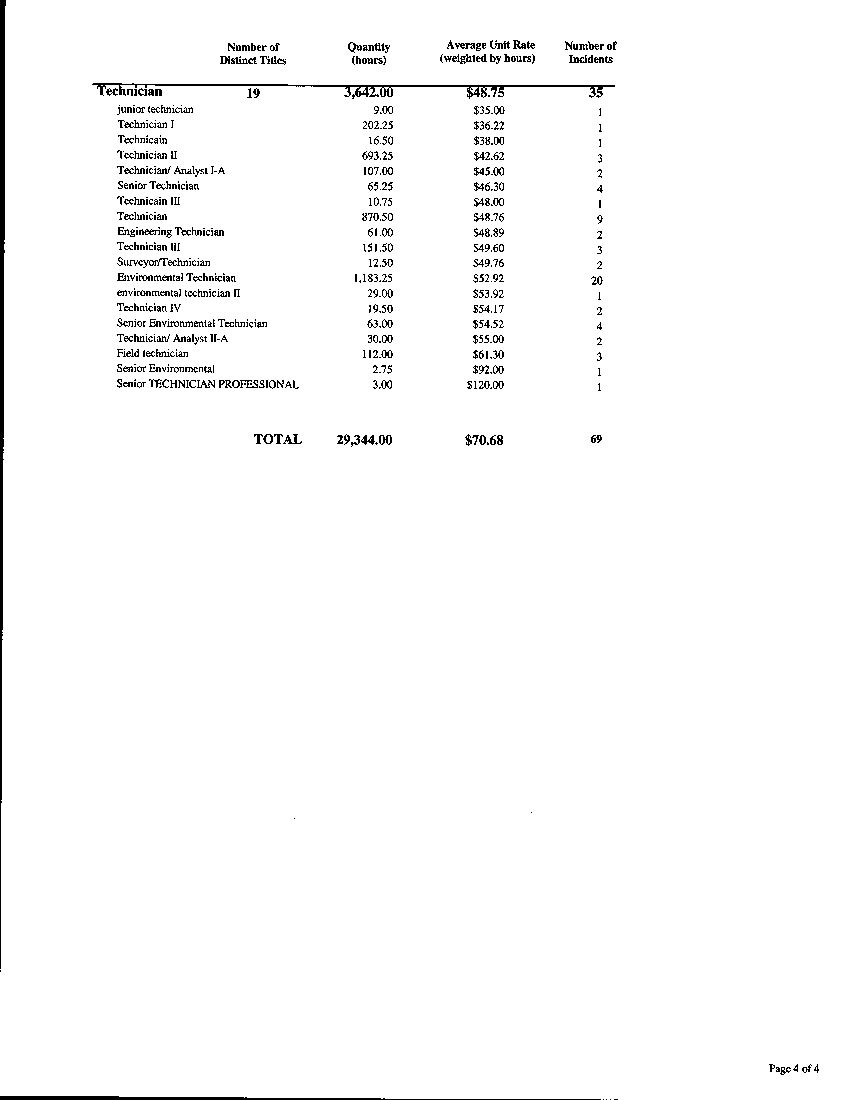

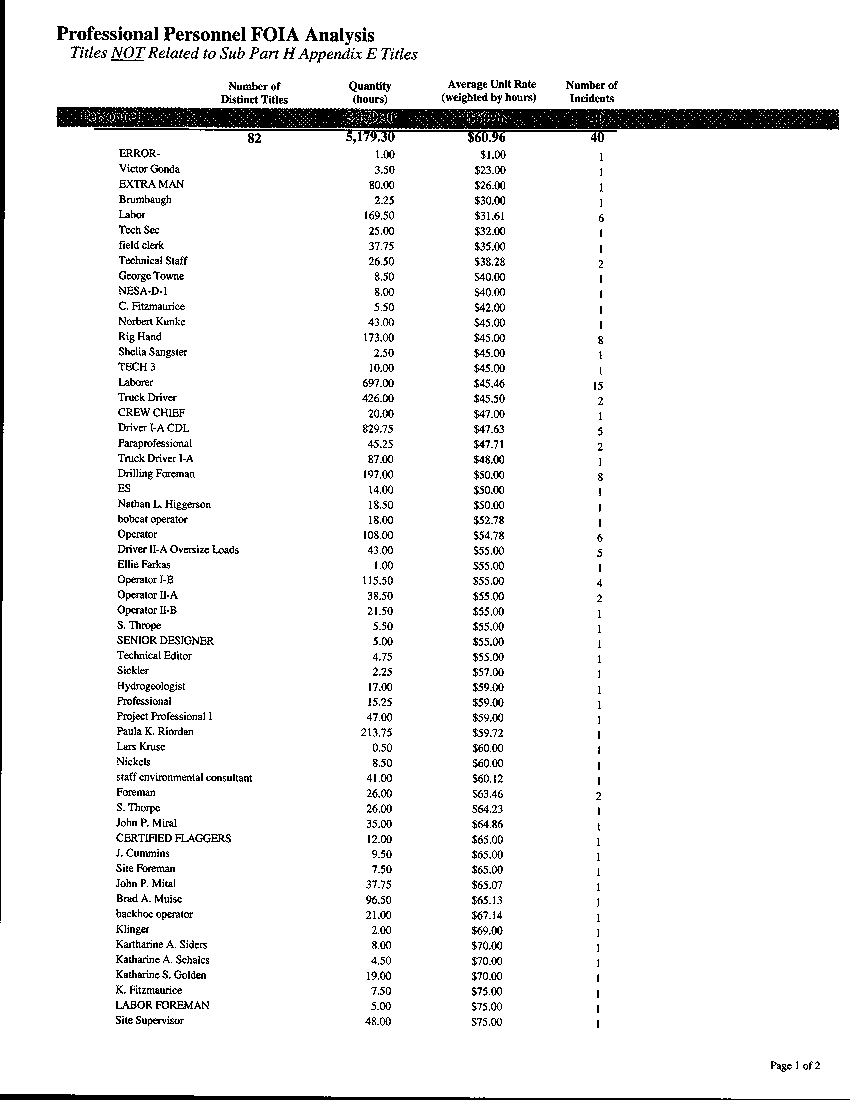

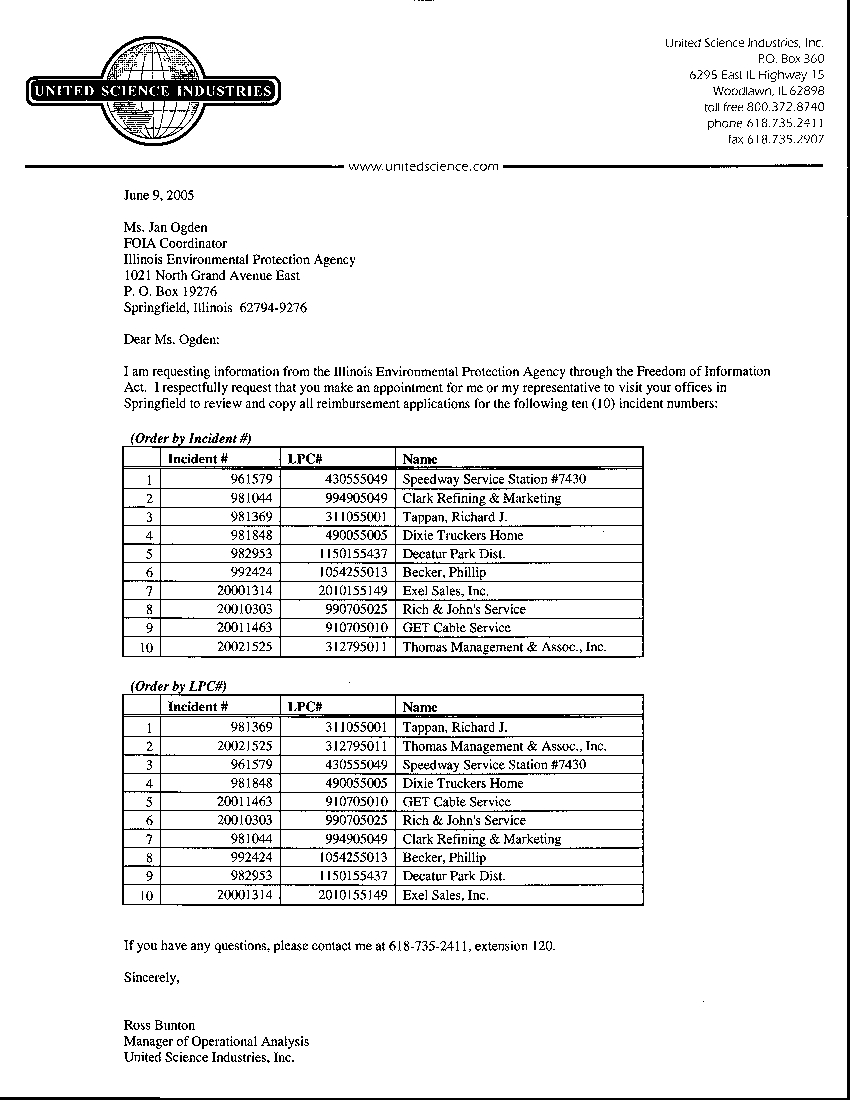

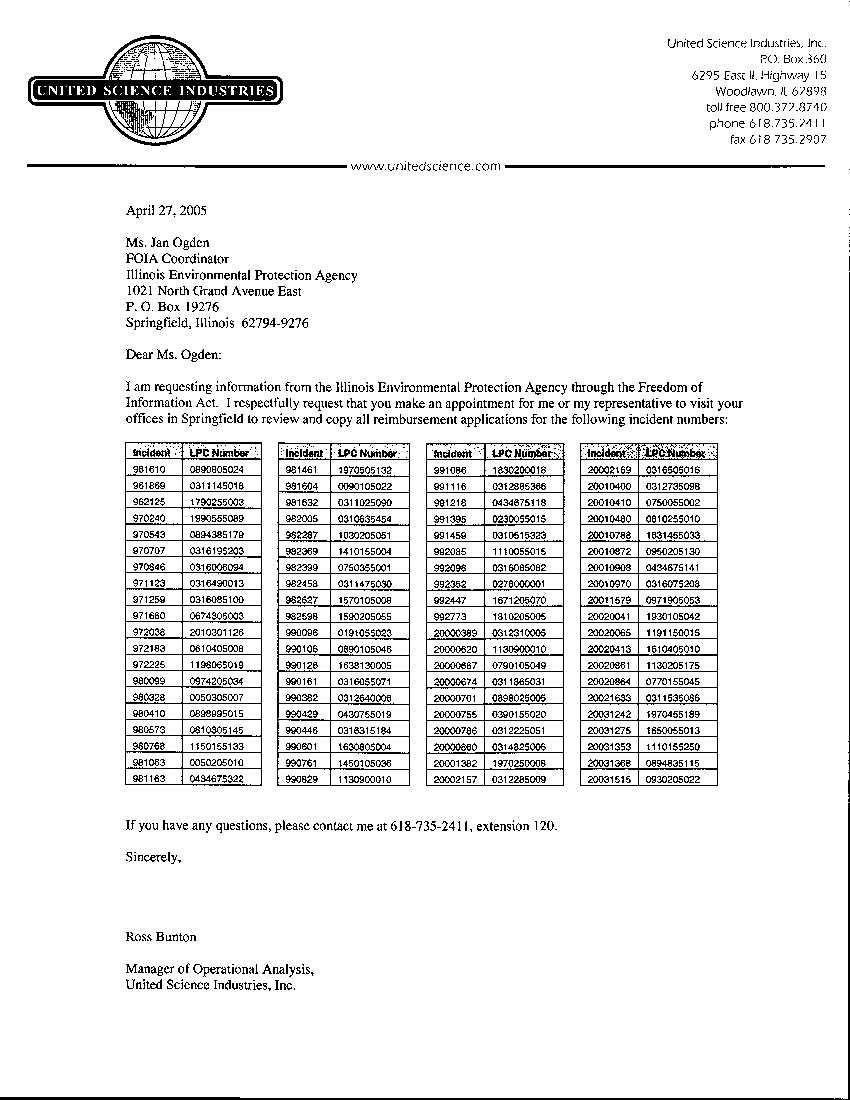

In order to evaluate the current and historical reimbursement practices of the

Agency on projects other than just USI’s client’s sites, USI performed a review of the

professional service costs associated with sixty-nine (69) randomly selected incidents.

These records were obtained via a Freedom of Information Act that was submitted to the

Agency earlier this year. (The methods that were used to select these incident numbers

along with a list of the incident numbers for each of the sixty-nine sites selected for the

sample is provided in Attachment 6) The results of the survey were very revealing and

prove that the maximum payment amount for professional services that have been

proposed by the Agency are not even close to being consistent with the costs that the

Agency currently approves. Most notably, the results of the survey showed that the

maximum payment amounts proposed by the Agency in Subpart H would have the effect

Page 32 of 49

of dramatically reducing the number of professional service hours and the costs that the

Agency currently considers reasonable and necessary.

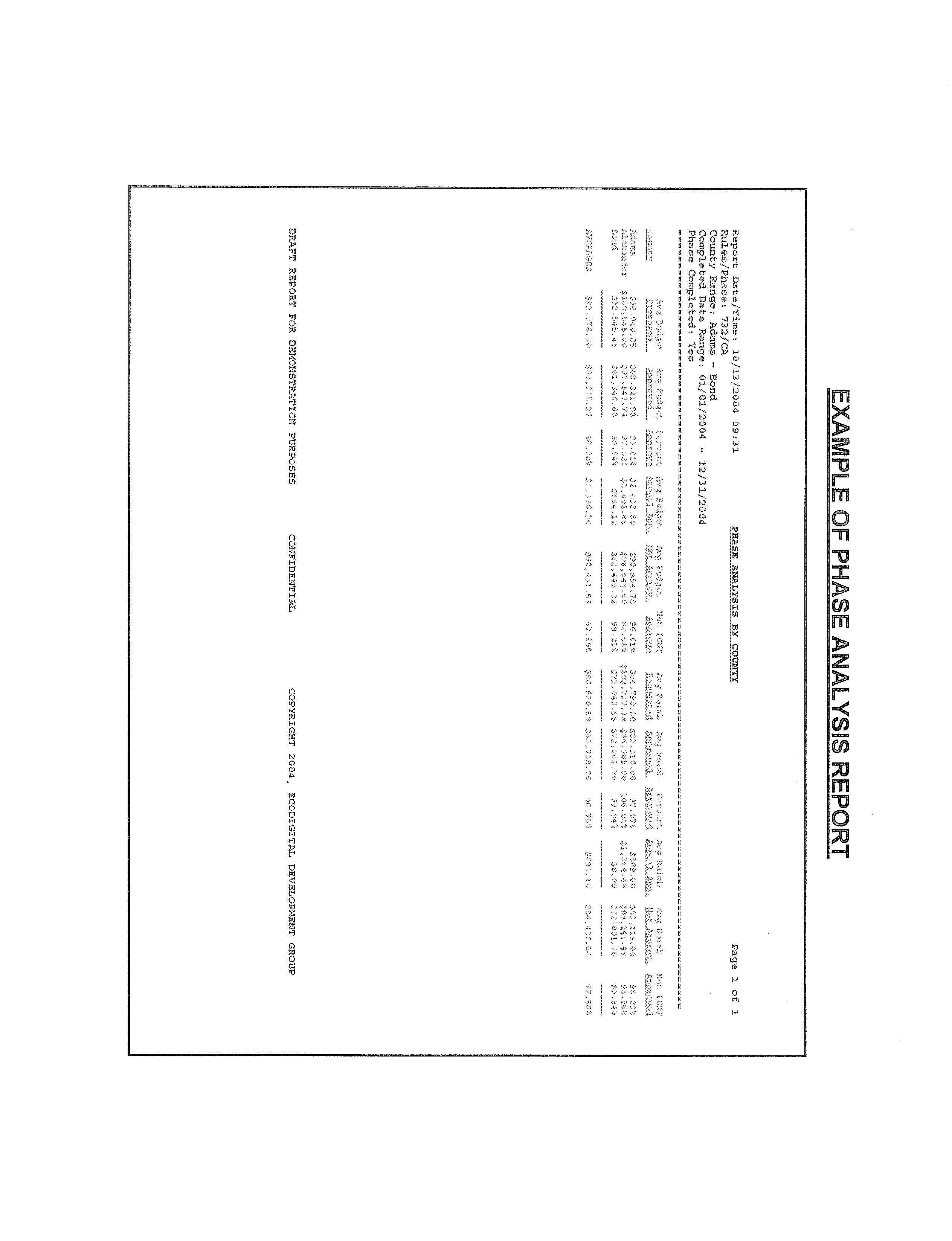

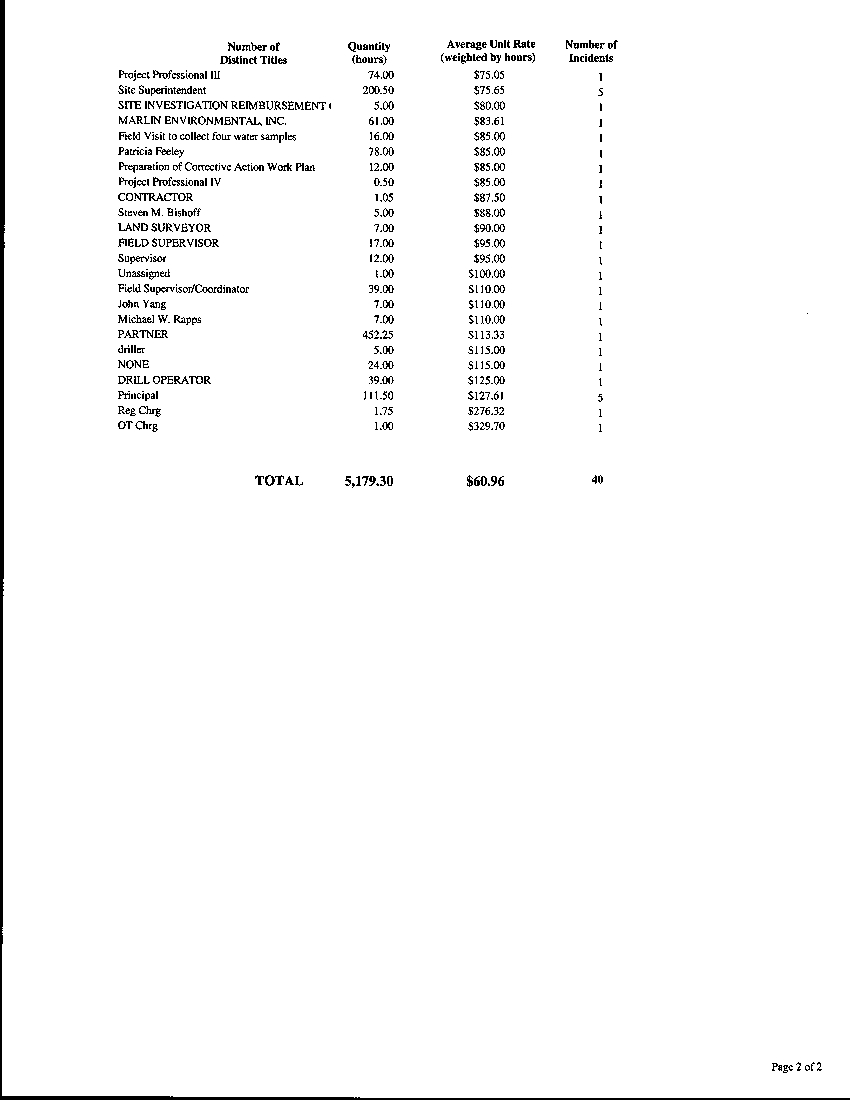

The data collected as part of this survey is reported by total professional service

hours and total charges per phase of a project (i.e. Early Action, Site

Classification/Investigation, Corrective Action) rather than on a task by task basis. This

is due to the fact that a task-by-task analysis would be statistically meaningless and

highly inaccurate due to the fact that the Agency has never implemented a standardized

task structure against which costs must be reported by owners/operators and their

consultants. Instead owners/operators and their consultants have historically been

permitted to group varying work activities into task that are arbitrarily established and

completely inconsistent across the Agency’s files. In fact, USI’s survey found 145

different task conventions associated with the Early Action Phase, 386 different task

conventions associated with the Site Classification Phase and 534 different task

conventions associated with the Corrective Action phase.

The effect of this lack of

standardization at the task level is that the only accurate means of assessing professional

service cost are either to assess them at the project level or on a phase by phase level.

Since the Agency’s current regulations are written utilizing a phase by phase approach

and the Agency’s budget and billing forms require budgets per phase, USI elected to

utilize a phase by phase approach in its review of the data. This is appropriate in light of

the fact that the Agency elected to use a phase by phase approach for professional

consulting services maximum payment amounts provided under Subpart H. It should be

noted that in Subpart H the Agency provides 32 tasks (maximum payment items) for all

phases of a UST project. USI is not suggesting that a consolidation and standardization

Page 33 of 49

of tasks is not a concept without merit, rather only that the methods that the Agency used

to accomplish this consolidation were horribly flawed, highly inaccurate and far from

being consistent with current Agency reimbursement practices.

The summarized results of this survey are follows.

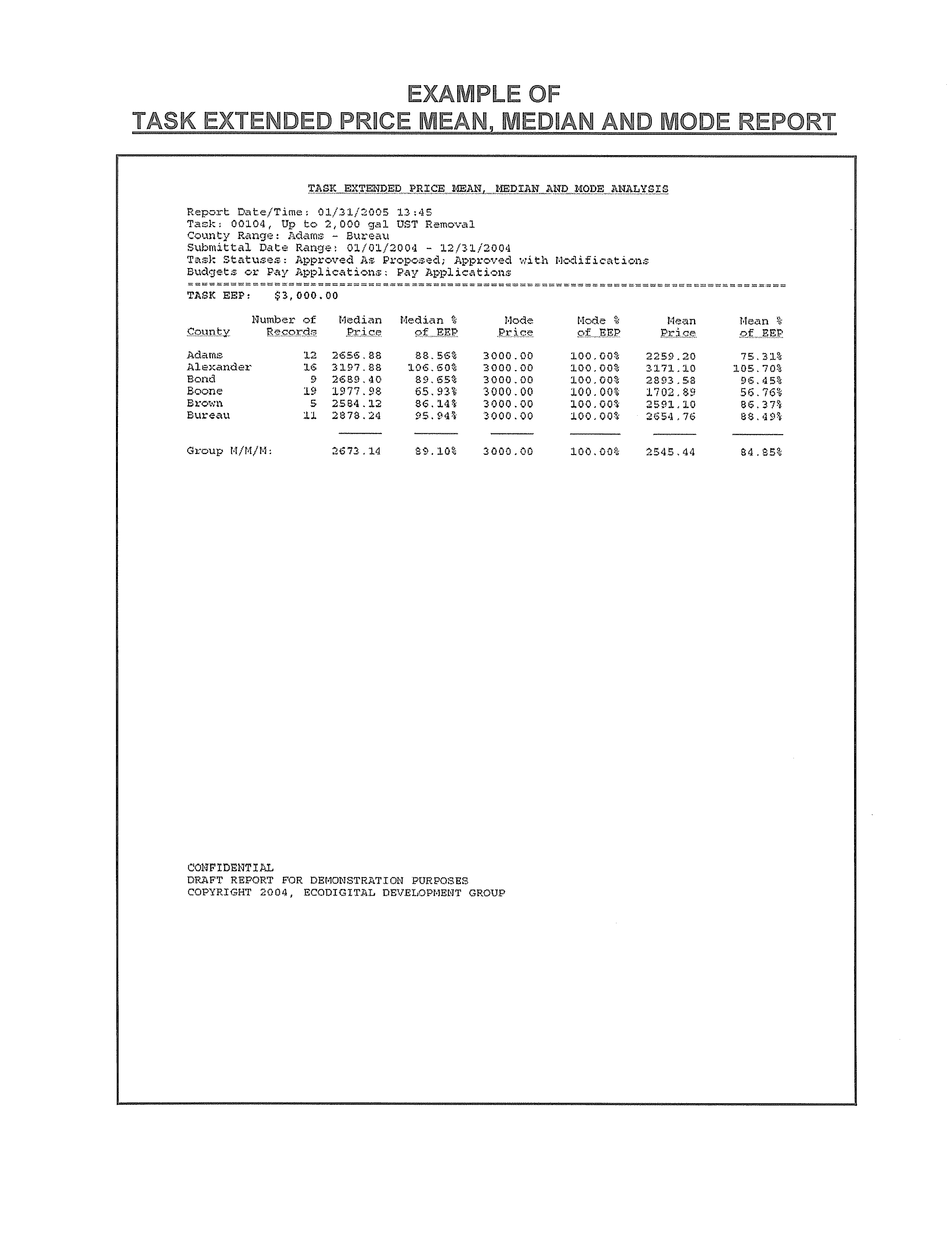

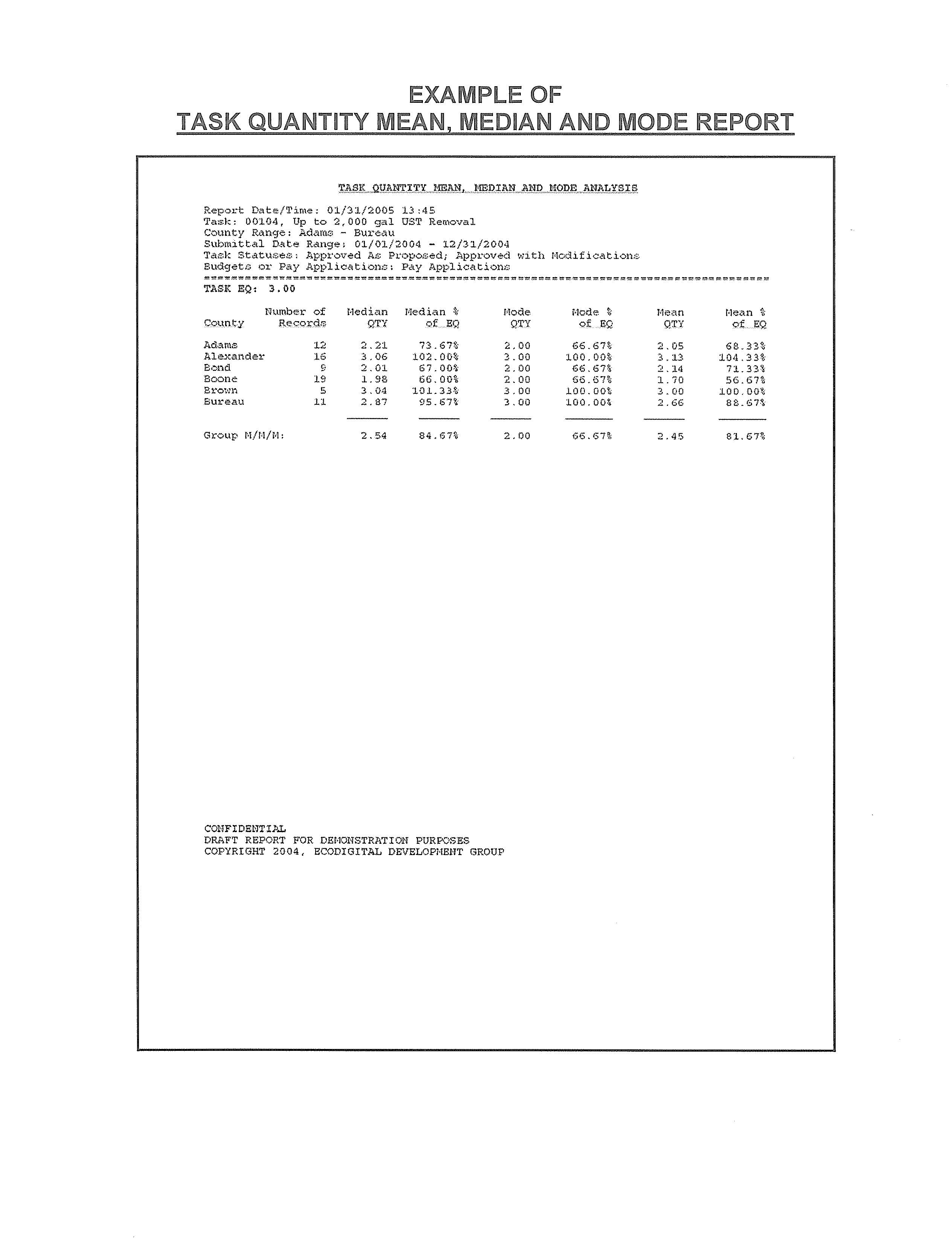

Professional Consulting Services Cost- Early Action

USI found that the average cost per hour for professional services plus one

standard deviation multiplied times the average number of hours for professional

consulting services for the Early Action Phase plus one standard deviation, yielded a total

cost of approximately $12,400. USI found that the average cost per hour for professional

services plus two standard deviations multiplied times the average number of hours for

professional consulting services for the Early Action Phase plus two standard deviations,

yielded a total cost of approximately $20,200.

Professional Consulting Services Cost- Site Classification/Site Investigation

USI found that the average cost per hour for professional services plus one

standard deviation multiplied times the average number of hours for professional

consulting services for the Site Classification/Investigation Phase plus one standard

deviation, yielded a total cost of approximately $17,300. USI found that the average cost

per hour for professional services plus two standard deviations multiplied times the

average number of hours for professional consulting services for the Site

Classification/Investigation Phase plus two standard deviations, yielded a total cost of

approximately $26,400.

Professional Consulting Services Cost- Corrective Action

Page 34 of 49

USI found that the average cost per hour for professional services plus one

standard deviation multiplied times the average number of hours for professional

consulting services for the Corrective Action Phase plus one standard deviation, yielded a

total cost of approximately $31,900. USI found that the average cost per hour for

professional services plus two standard deviations multiplied times the average number

of hours for professional consulting services for the Corrective Action Phase plus two

standard deviations, yielded a total cost of approximately $49,800.

USI will provide at the July 27

th

hearing, a detailed description of the means and

methods that were used to collect and analyze this data as well as all of the supporting

documentation and details and other relevant statistics.

The Agency has attempted to portray that many of the tasks associated with the

maximum payment amounts provided in Sections 734.845 require similar levels of effort

from one project to the next. This is generally not the case. USI intends to supplement

this written testimony with visual aids that will be provided at the hearing. These visual

aids will help clarify the record on this matter. Secondly, the Agency has attempted to

portray that, as an organization, it is uniform and consistent in its reviews, and that the

actions of its reviewers have little impact on the level of professional services and costs

that are required to be incurred in order to comply with its regulations. This is evidenced

in the Agency’s testimony when they state that the amount of time that the Agency takes

in reviewing a submittal is largely based on the quality of the submittal. (Opinion and

Order at 17). It is also evidenced when they state that the “The Agency has always

strived to maintain uniformity consistency and objectivity in its reviews and will continue

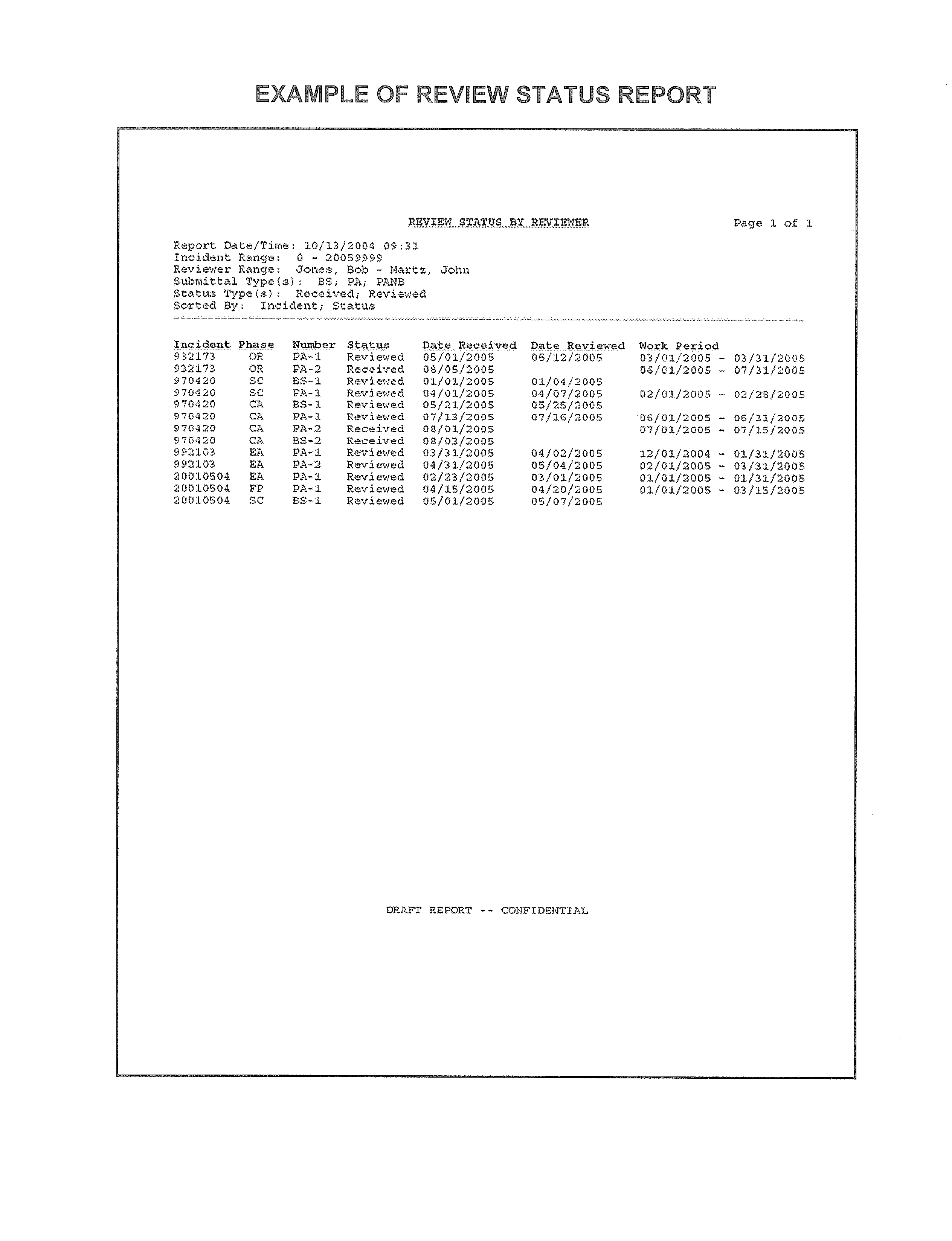

to do so in the future.” (IEPA June 15, 2005 Answer to Jay Koch’s Question 33). USI

Page 35 of 49

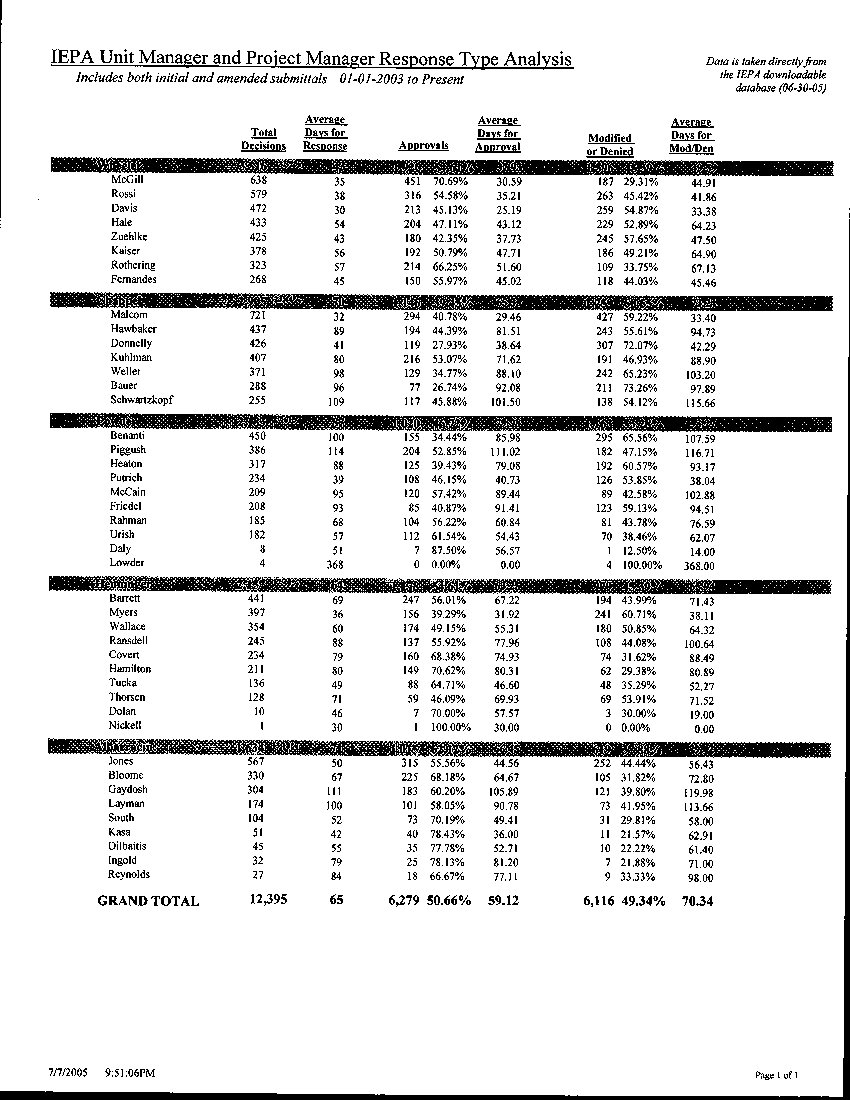

does not agree that the Agency is uniform and consistent in its reviews and submits as

Attachment 7 report summarizing information taken from the Agency’s own web site that

shows that their reviews on a statewide basis are highly erratic. This also serves as a

strong indication that the decisions of individual Agency reviewers have an impact on the

total costs of professional services relative to a particular underground storage tank site.

Section 4

Synopsis of Non-Objectionable Provisions

USI has reviewed Sections 734.810 through 734.840 of the proposed rule to

determine separately whether USI has any objections to the language of those provisions

and whether USI has any objection to the maximum payment amounts proposed in each

Section. USI is not objectionable in concept to the language of any of those provisions.

In evaluating the appropriateness of the maximum payment amounts proposed in

each Section USI applied several tests to determine the adequacy of the maximum

payment amount. If the maximum payment amount published in Section 734.810

through 734.840 passed all of these tests, then USI does not object to the maximum

payment amounts published in that Section. The test criteria utilized are as follows:

1.

Test 1- Unit of Measure Test

. For this test USI asked is the “unit of measure”

assigned to the work activity (task) appropriate? In answering this question

USI considered whether the task was likely to be highly variable in scope of

work or have a well defined scope of work. If the scope of work appeared to

be well defined then USI considers a lump sum or unit price “unit of measure”

to be appropriate. On the other hand, if the scope of work is undefined or is

defined but likely to be the type of work that is inherently unpredictable, then

Page 36 of 49

USI’s opinion would be that the “unit of measure” assigned to the task should

be scalable so that as the work increases or decreases the total compensation

would be adjusted accordingly. A task in this category would not be

expected to be assigned a “lump sum” unit of measure. To illustrate how USI

applied this test the following example is provided. In Section 734.820 a

maximum payment amount is provided for “hollow stem auguring”. The

assigned “unit of measure” for hollow stem auguring is “per foot”. USI

determined that this was an appropriate unit of measure due to the facts that

the number of feet drilled during any investigation could vary significantly. A

“per foot” unit of measure is scalable and therefore seems appropriate.

Test 2

-

Competitive Bidding Test

- The competitive bidding provisions provided

in Section 734.855 are intended to provide the owner operator with a means of

establishing an alternative maximum payment amount if the owner operator believes that

the published maximum payment amount is not sufficient. In order to effectively utilize

the competitive bidding provisions of Section 734.855 as a means of establishing an

alternative maximum payment amount its is necessary to demonstrate pursuant to

734.855 that the cost will “…cover all of the costs included in the maximum payment

amount that the bid is replacing” (Order at 316) The only way to be certain that a bid

request and its corresponding bids “covers all of the costs included in the maximum

payment amount that the bid is replacing” is to mirror, in the bid specification, the scope

of work published in the regulations for the applicable maximum payment amount.

Therefore, the second test that USI used to evaluate the appropriateness of the maximum

payment amount was to consider if the regulations in Sections 734.810 through 734.840

Page 37 of 49

provided sufficient detail to allow a scope of work to be authored in a way that accurately

matches the scope of work provided in Sections 734.810 through 734.840. If, in USI’s

opinion, the scope of work described in the regulations provided enough definition for a

bid specification to be authored to the standard prescribed in Section 734.855, then the

maximum payment amount passed this test. If the scope of work provided in the

regulations did not provide sufficient detail, then the maximum payment amount would

be disqualified as conceptually flawed. [please note that USI used its experience in

contracting and the following definition of “scope of work” when applying this test.

Definition: A scope of work is a detailed description of the work specifying the task and

activities that are reasonably contemplated by the parties prior to the initiation of the

work, including measurable objectives useful for determining successful completion.]

Test 3- Accuracy and Reasonableness of Price

The third and final test that USI used to evaluate the appropriateness of the

maximum payment amounts published in Sections 734.810 through 734.840 is

whether or not USI believes the price accurately reflects prevailing market

prices and is reasonable and inclusive of the conditions that are likely to be

encountered at most LUST sites in Illinois. It is obviously important to the

Illinois EPA and the Board that the prices not be set too high. However, given

the fact that significant costs are likely to be associated with the competitive

bidding process required in Section 734.855 it is equally important that the

maximum payment amount not be set too low. If the price is set too low, the

effect is likely to be the creation of countless bid specifications and request

and all of this additional work will come at a cost. Maximum payment

Page 38 of 49

amounts that are set too low only invite additional costs to be accrued against

the UST program and are not in anyone’s best interest.

Sections 734.810 through 734.840 are generally related to investigatory or

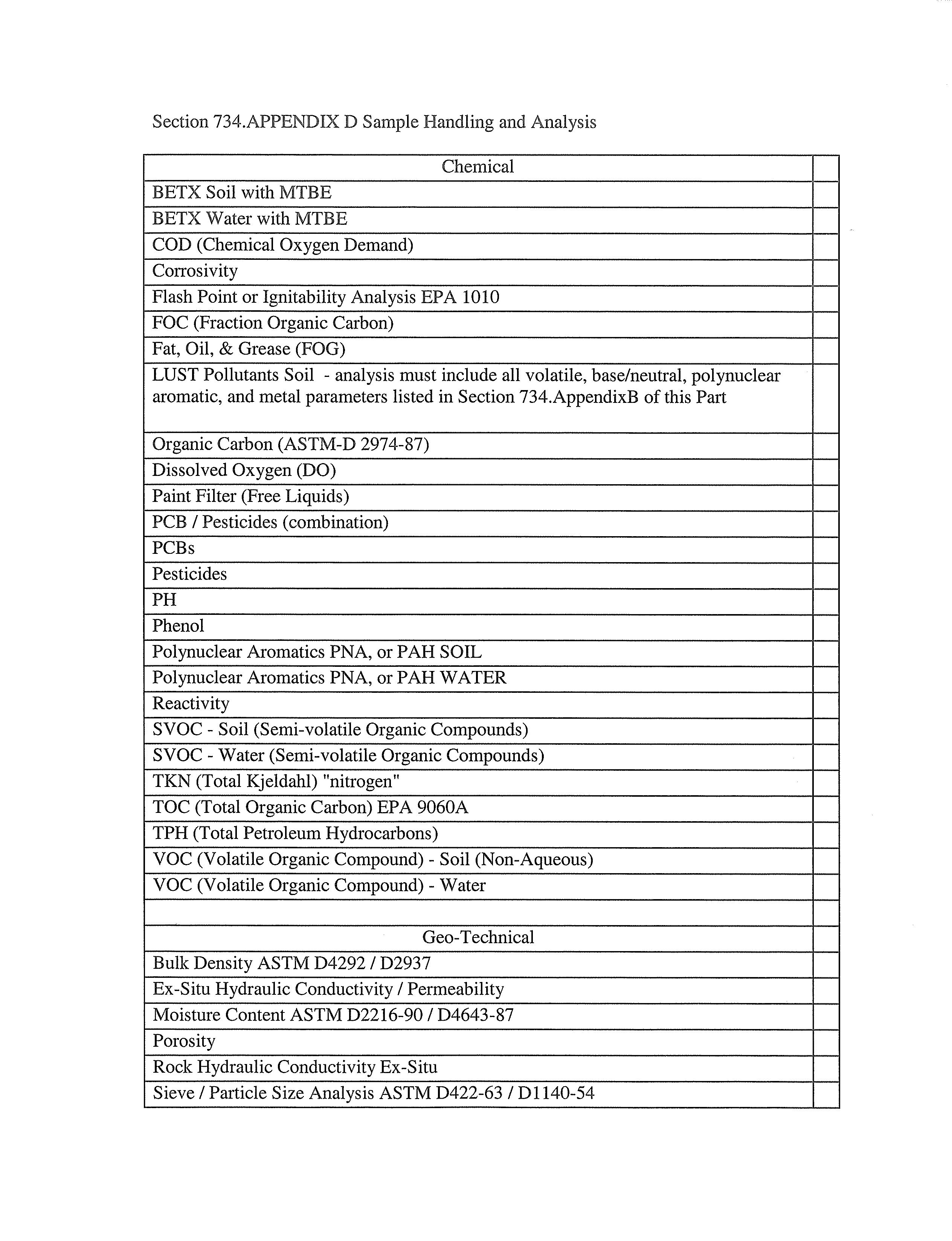

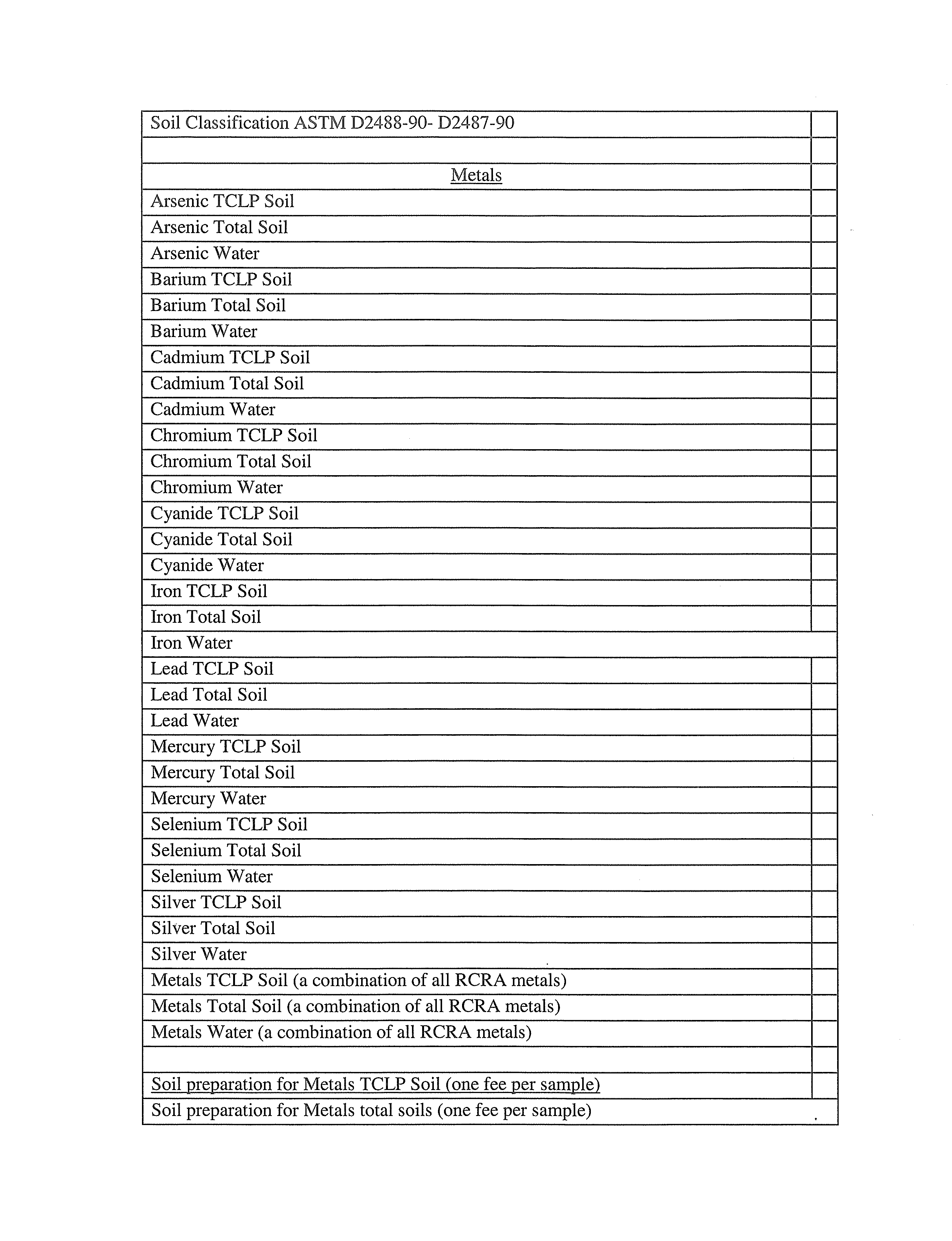

remedial field services and analytical work. These Sections of the regulations create 109

maximum payment amounts (including as a separate payment amount the price for each

sample type specified in Appendix D). As a result of performing the above described test

on the 109 maximum payment amounts provided in Sections 734.810 through 734.840,

and with the exception that USI disagrees with the Agency’s omission of a maximum

payment amount for mobilization for the drilling activities provided in Section 734.820,

USI believes the maximum payment amounts are appropriate and has no objection to

their implementation. A detailed list of the maximum payment amounts created in each

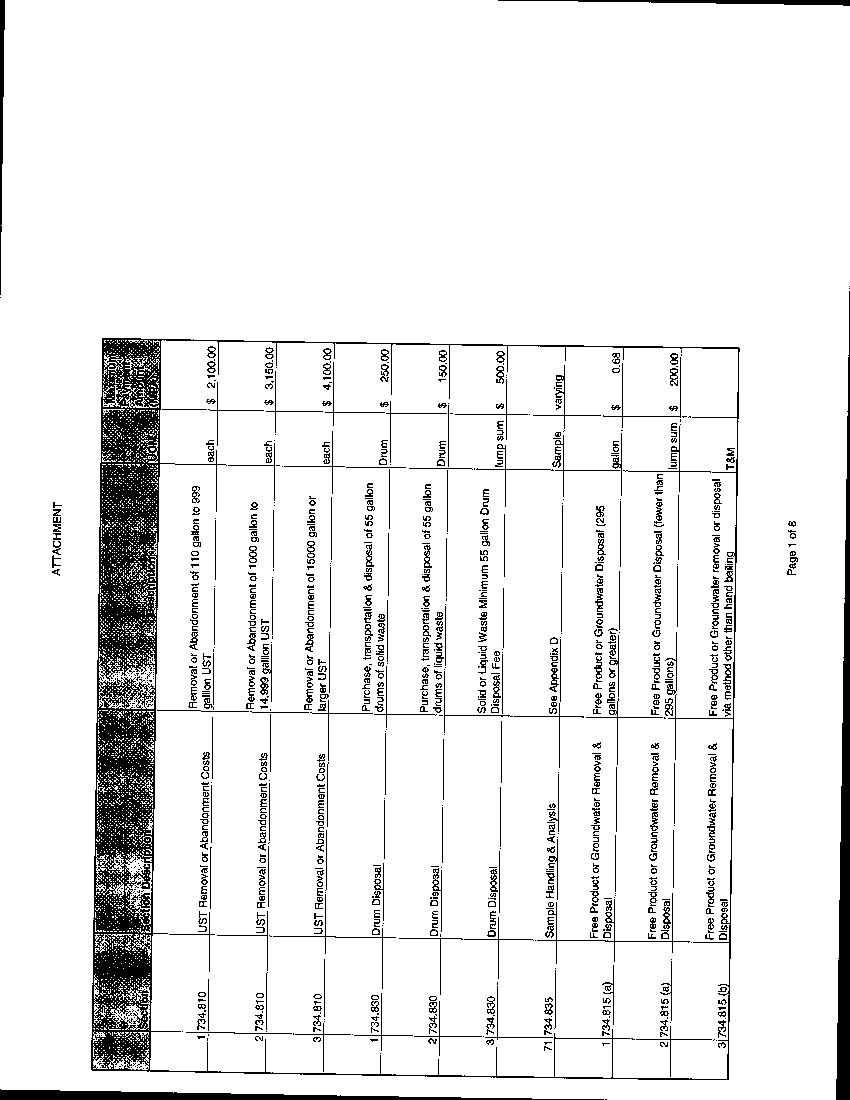

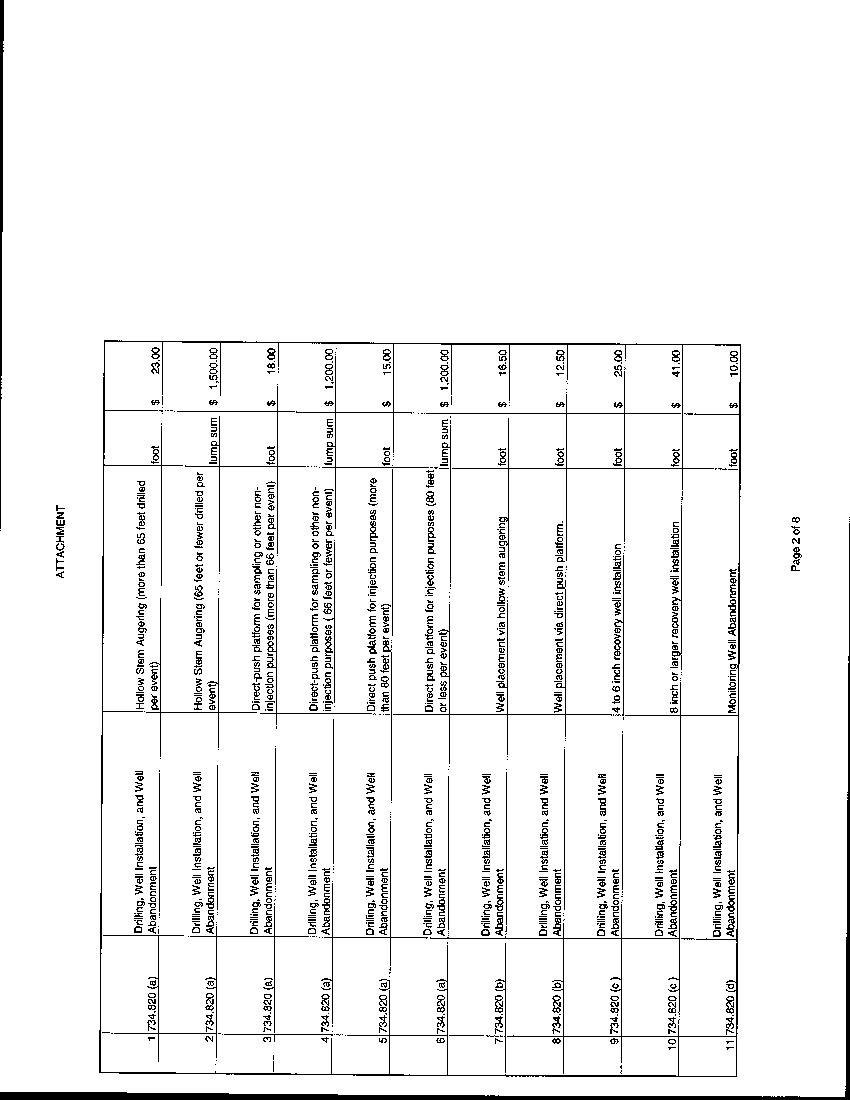

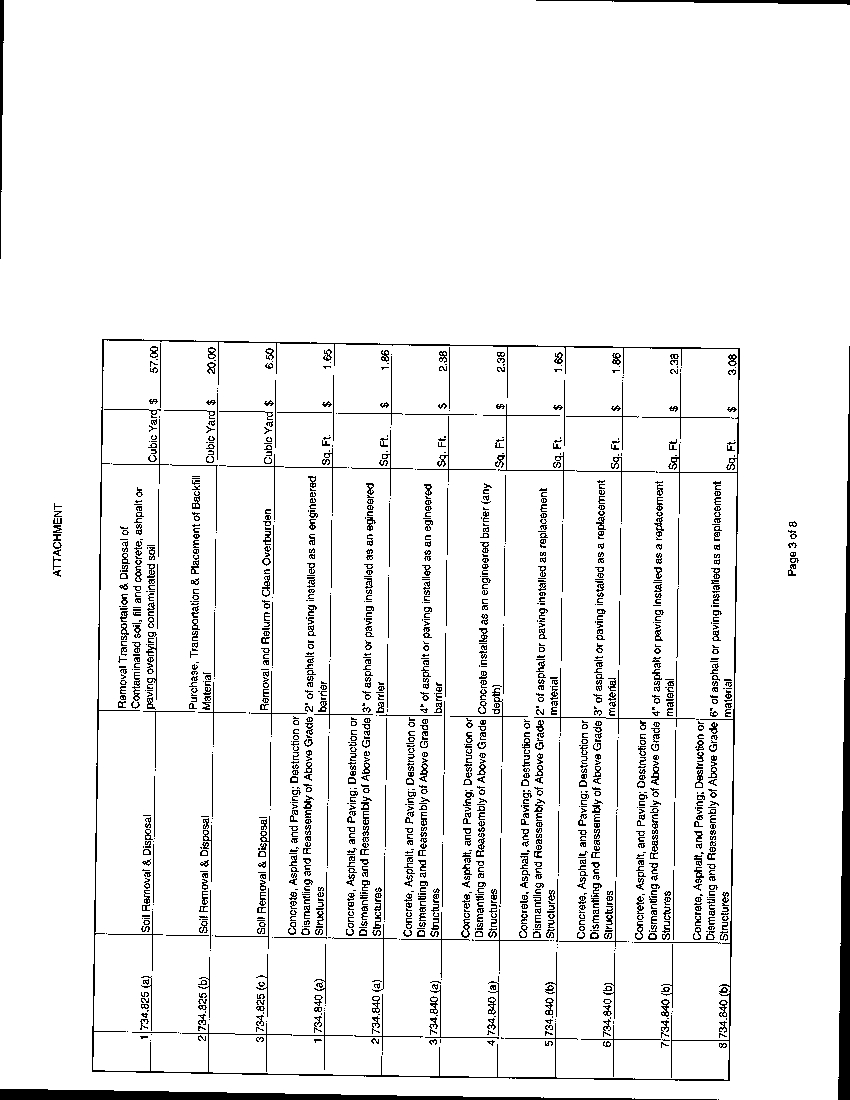

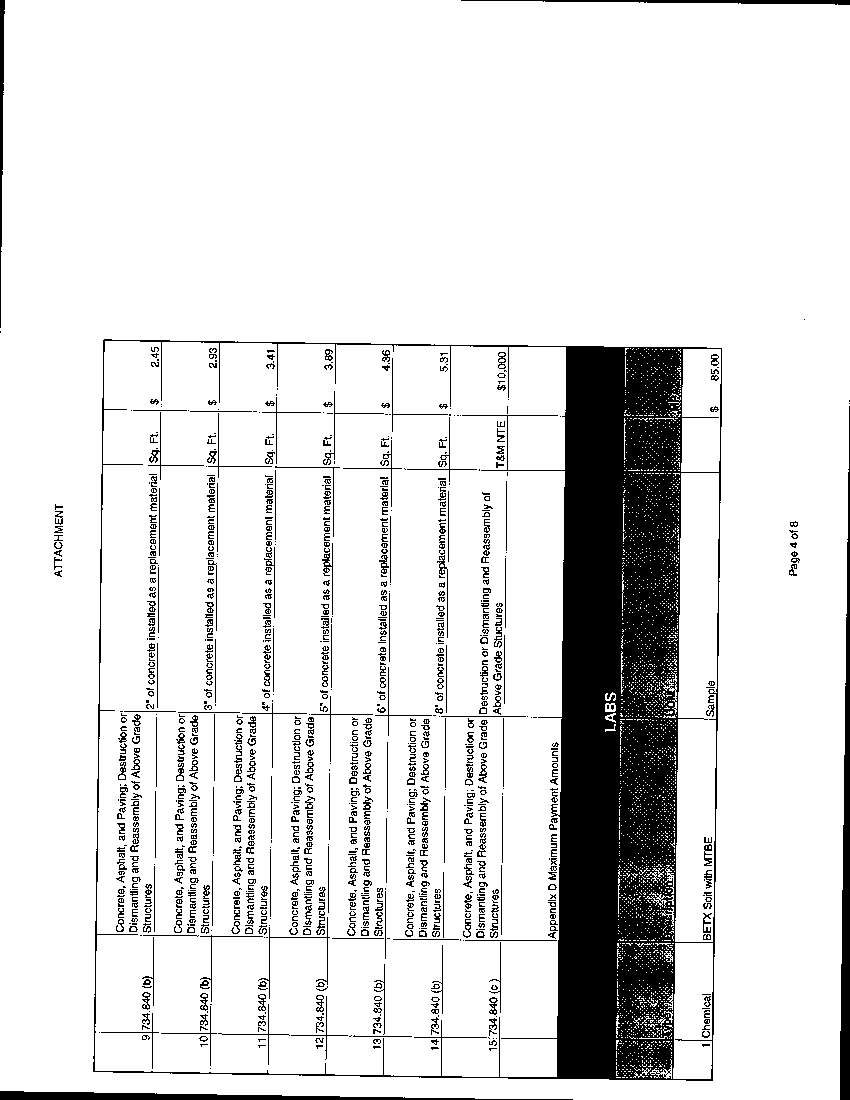

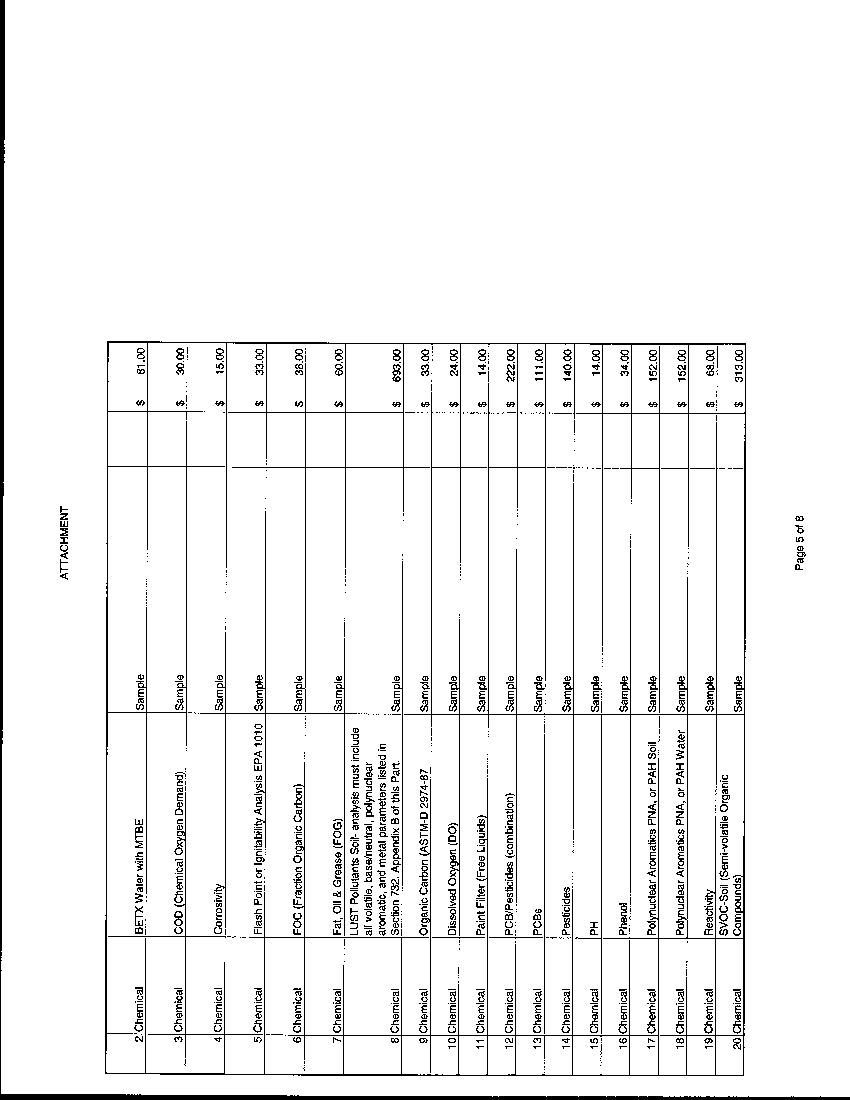

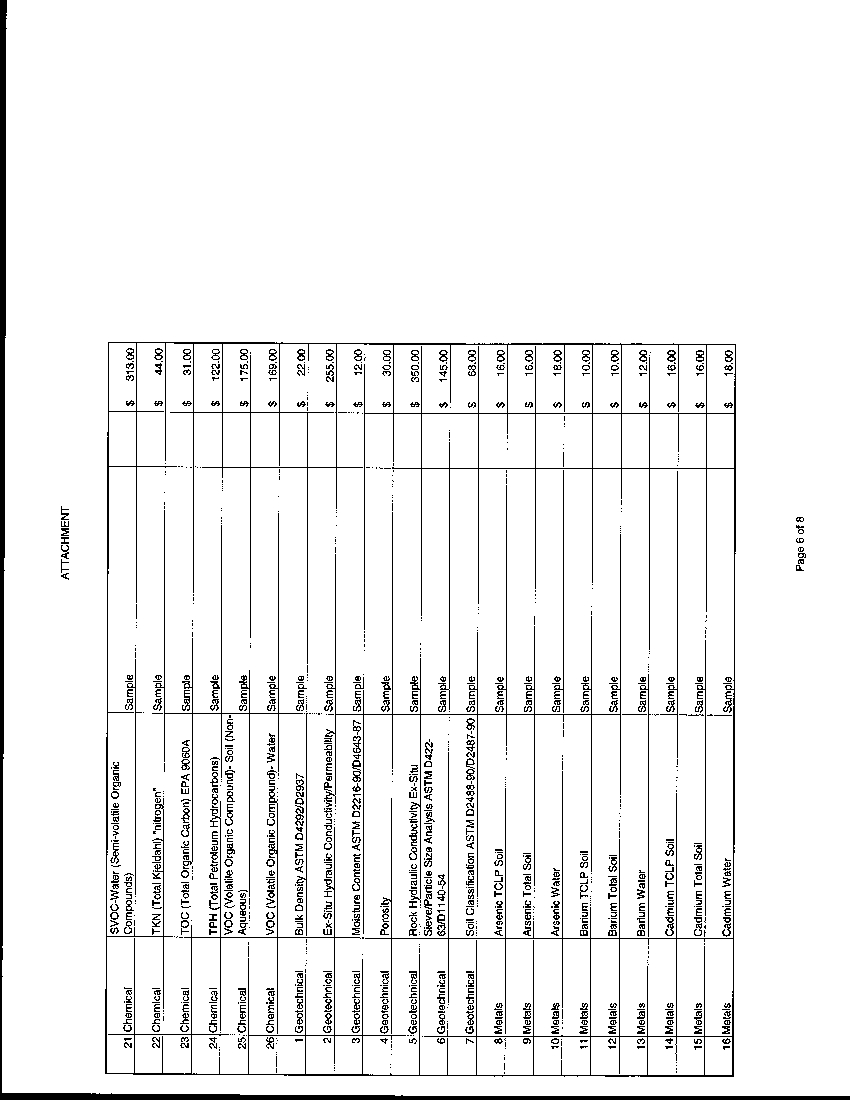

Subpart H Section from 734.810 through 734.840 is provided in Attachment 8.

Section 5-

Conceptually Flawed & Intolerable Provisions

Conceptually Flawed and Intolerable Provisions

Although several financial aspects of the proposed regulations are notably flawed

and inappropriate, the majority of concern is centralized around one primary subject: the

lack of a defined scope of work associated with Subpart H and lump sum Professional

Service payment items for professional services. Even within Subpart H Section 734.800

Applicability, eight (8) references are made to “tasks” which are present throughout

Sections 734.845. The term “task” is utilized within Section 734.800 to denote activities

which must be completed as a part of applicable Subpart H pay items. However, upon

review of all pay items listed within Section 734.845, the specific listing of any of the

Page 39 of 49

aforementioned “tasks” cannot be found. Furthermore, the term “task” in Section

734.800, which implicitly references “tasks” which are to be completed as a part of

applicable Subpart H Professional Service pay items, is not referenced in any subsequent

sections.

It is understood that the intent of Section 734.800 is to provide owner/operators

with two (2) alternative means for determining applicable “maximum” payment amounts

when standardized rates cannot be met. Unfortunately, however, this process is erred in

concept and is certain to create undue financial and administrative stress on the

owner/operators. The premise behind this argument resides in the description of what a

“scope of work” is. By definition, the phrase “scope of work” denotes a detailed

description of the work (inclusive of a substantive task breakdown), including measurable

objectives useful for determining successful completion. As stated within this testimony,

specific tasks have not been included or delineated throughout professional service

Subpart H pay items whereby one might ascertain what measurable objectives were in

fact completed. This point was alluded to in several questions submitted by Daniel King

of USI which were vaguely answered with blatant disregard to the regulated community

and their representatives.

The primary intent of USI’s line of questioning was to

determine the applicable Subpart H payment items (or lack thereof) associated with

required scopes of work required by 734 regulations. For example, Section 734.210(a)

requires that:

“Upon confirmation of a release of petroleum from an UST system in accordance

with regulations promulgated by the OSFM, the owner or operator, or both, must

perform the following initial response actions with 24 hours after the release:

1)

Report the release to IEMA (e.g., by telephone or electronic mail);

2)

Take immediate action to prevent any further release of the

regulated substance to the environment; and

Page 40 of 49

3)

Identify and mitigate fire, explosion and vapor hazards.”

USI’s Question #1 (Please refer to Daniel King’s questions submitted, May 3 on behalf

of USI) merely asked if the Agency would be willing to address the completion of this

scope of work through an additional maximum pay amount or if the Agency intended for

costs associated with 734.210(a) to be completed under a current Subpart H pay item and

if so, which

specific

pay item should be utilized. As noted in Response #1 on page 2 of

the Agency’s June 14, 2005 response to Mr. King’s questions, all associated activities

were accounted for “throughout Subpart H”. A detailed review of all Subpart H

Professional Service pay items clearly reveals the lack of the aforementioned tasks. The

Agency’s response purposefully skirted the question at hand by addressing other Early

Action field activities (such as tank removal, free product removal, soil removal, etc).

The environmental industry, in addition to the regulated community, are aware that the

scope of work in 734.210(a) obviously includes remarkably different activities, including

such things as emergency response and spill oversight, none of which are specifically

included in any Subpart H pay item. This lack of the regulating authority to openly

address issues between required technical scopes of work without adequate compensatory

measures for the owner/operator undermines the intent of the LUST program and thus the

ability of UST owners and operators to meet their financial obligation. Further neglect

upon the Agency’s behalf in addressing required scopes of work which are

not

compensated under Subpart H occurs numerous times throughout the proposed

rulemaking. The continued discussion hereafter will focus on how the inability to define

and delineate any scope of work within 734 affects any alternative proposal for pricing

variances.

Page 41 of 49

The first alternative to utilizing the Subpart H maximum payment amounts, as

noted in Section 734.800(a), is the process of competitive bidding. These provisions,

provided in Section 734.855, are intended to provide the owner/operator with a means of

establishing an alternative maximum payment amount if the owner/operator believes that

the published maximum payment amount is not sufficient. This concept requires that a

minimum of three (3) bids be obtained with award given to the low bidder and that bids

“must include all costs

included in the maximum payment amount that the bid is

replacing” and “be based upon the same scope of work”

(Opinion and Order; pg. 316).

As noted above, specific tasks and scopes of work are not listed in which to prepare

adequate bid specifications for subcontractor’s to bid on. To assume that all costs must

be included within bidding documentation without providing an adequate description of

the tasks associated with those costs is ambiguous in nature. The only way to be certain

that a bid request and its corresponding bids “covers all of the costs included in the

maximum payment amount that the bid is replacing” is to mirror, in the bid specification,

the scope of work published in the regulations for the applicable maximum payment

amount. Therefore, the second test that USI used to evaluate the appropriateness of the

maximum payment was to consider if the regulations in Sections 734.845 provided

sufficient detail to allow a scope of work to be created in a bid specification that

accurately matches the scope of work provided in Sections 734.845. If the scope of work

described in the regulations provided enough definition for a bid specification to be

prepared to the standard prescribed in Section 734.855, then the maximum payment

amount would pass this test. If the scope of work provided in the regulations did not

Page 42 of 49

provide sufficient detail, then the maximum payment amount would be disqualified as

conceptually flawed.

Another visible trend within the Agency’s answers to Mr. King’s questions is the

arbitrary grouping of items within applicable Subpart H payment amounts. In this,

specific regulatory tasks listed throughout the regulations are nonchalantly lumped into

the most relative Subpart H pay item. Additionally, the costs associated with various

regulatory requirements may be divided amongst multiple phases of work prior to being

lumped into non-specific pay items. The Agency's answer to Mr. King's question number

20 provides an excellent example of this arbitrary grouping and why a defined scope of

work is necessary if competitive bidding is to be used as an alternative to the maximum

lump sum payment amounts for professional services. The Agency answered Mr. King's

question by stating that some of the costs of a well survey conducted pursuant to 445 (b)

were included in the maximum payment amount for 20 and 45 day reports 734.845 (a) (3)

and that the balance (the labor cost only) is covered by 734.845 (b) (7). 734.845 (a) lists

the maximum payment amounts for professional services associated with Early Action

activities and 734.845 (b) lists the maximum payment amounts associated with Site

Investigation activities. To complicate matters further, the IEPA suggested that the costs

for the professional engineer's review and certification of the well surveys be included

within 734.845 (b) (relating to Site Investigation) and 734.845 (c) (relating to Corrective

Action). Obviously, with this level of complexity in the formulation of the maximum

payment amounts and the fact that none of this has been communicated to the regulated

community, it will be impossible to: 1.) obtain competitive bids that match the scope of

work contemplated by the IEPA in section 732.845/734.845 or 2.) determine if any bid

Page 43 of 49

obtained meets or exceeds the maximum payment amount provided in Sections

732.845/734.845. It would not have been reasonable for a member of the regulated

community to know that this water supply well survey should have been included as part

of the maximum payment amount found in 734.845 (a) (3) and this certainly

demonstrates that without a well defined and published scope of work for each

professional service maximum payment amount, the competitive bidding and unusual or

extraordinary provisions of Subpart H are of no utility.

The Board has indicated that “the inclusion of bidding in the proposal will assist

in achieving the Agency's stated goals to streamline the UST remediation process, clarify

remediation requirements, determine market rates for costs and "most notably" reform the

budget and reimbursement process" in its Opinion and Order; pg 67. What is obvious to

individuals within the industry, however, is the inflammatory affect competitive bidding

will have on rates within environmental compliance work. Upon first glance, one would

assume that competitive bidding would effectually reduce costs within a specific task.

Without the requisite specificity in the bidding process, subcontractors are forced to

inflate bids to cover unforeseen expenditures not listed in the available specifications.

This conceptual flaw, pertaining specifically in this case to report submittal, was

addressed in Mr. King’s question #46 (Daniel King’s Questions submitted on behalf of

USI; pg. 10) which asked “pursuant to 734.845 Professional Consulting Services, how

many submittals are included in each unit rate reporting pay item?” In the Agency’s

answer to Mr. King's question #46, the Agency states that their maximum payment

amounts for professional services consider the submission of all plans and reports

irrespective of the number of times a particular plan or report must be submitted.

The

Page 44 of 49

number of times that the Agency may request an additional report is highly erratic and

unpredictable and without a defined number of submissions in relation to each maximum

payment amount it will be impossible to compare a bid to the maximum payment amount

and determine if the true costs is greater than or less than the maximum payment amount.

Thus, the process of competitive bidding, based on bidding unknown scopes of work, will

only serve to further diminish funding available to owner/operators. This renders the

competitive bidding provision of Subpart H useless as an alternative means of

establishing maximum payment amounts for professional services under Subpart H.

The third alternative the Agency proposes for payment of costs in excess of the

proposed Subpart H payment amounts is through the designation of “unusual or

extraordinary circumstances” (Opinion and Order; pg. 317, Section 734.860 Unusual or

Extraordinary Circumstances). The Agency's comment which reads: "Please note that

the unusual or extraordinary circumstances provisions focus on the circumstances present

at a site, not on particular tasks," demonstrates that the Agency intends to administer this

rule in a fashion that will prohibit the owner/operator from using the extraordinary

circumstances provision of 734.860 as a means to establish alternative maximum

payment amounts unless the entire site is somehow characterized as "unusual or

extraordinary". It’s clear, however, in 734.800 that the maximum payment amounts are

intended to be utilized on a task by task basis. It was also clearly the intent that an

owner/operator need only demonstrate that the circumstances with regard to a particular

task were unusual or extraordinary; not that some condition exists that would qualify the

entire site as unusual or extraordinary.

Page 45 of 49

The arbitrary nature of this option provides only minor support to the regulated

community given the inability to provide a definitive scope of work for each of the pay

items. By definition, the antonym of extraordinary and unusual is ordinary; however, as

noted earlier, “ordinary” is in no way defined or demonstrated throughout Subpart H.

Furthermore, the perception of ordinary vs. extraordinary will be based upon the

Agency’s tenure in office without substantive influence from the regulated community or

even other State agencies. An example of the ensuing conflict is referenced in the

questions submitted by Daniel King on behalf of USI. In question #6 (pg. 2), Mr. King

asks: