IN THE MATTER OF

WATER QUALITY AMENDMENTS TO

35 Iii. Adm. Code 302.208(e)-(g),

302.504(a)

302.575(d), 303 .444, 309.141(h); and

PROPOSED 35 Iii. Adm. Code 301.267,

301.313, 301.413, 304.120, and

309.157

NOTICE OF FILING

PLEASE TAKE NOTICE that on this date, September 6, 2002, I filed with Dorothy

Gunn, Clerk ofthe Illinois Pollution Control Board, James R. Thompson Center, 100 West

Randolph, Suite 11-500, Chicago, IL 60601, the enclosed Post-Second Hearing Comments of

Environmental Law and Policy Center, Prairie Rivers Network and Sierra Club.

Albert F. Etting

Albert F. Ettinger

Environmental Law and Policy Center

35 East Wacker Drive, Suite 1300

Chicago, IL 60601

(312) 795-3707

BEFORE THE ILLINOIS POLLUTION CONTROL BOARD

rc~

~.

~tiU2

)

~

r~

)

)

~‘

)

R02-11

)

(Rulemaking-Water)

BEFORE THE ILLINOIS POLLUTION CONTROL BOARD

it ~

L.PP~”~

IN THE MATTEROF:

)

SE!)

2UIJ~

)

WATER QUALITY AMENDMENTS TO

)

~

35 Ill. Adm Code 302.208(e)-(g), 302.504(a),

)

R02-1 1

~°~‘~/

~

302.575(d),

303.444, 309.141(h); and

)

(Rulemaking-Water)

PROPOSED 35 Iii. Adm. Code 301.367,

)

-

301.313, 301.413, 304.120, and 309.157

)

POST-

SECOND HEARING COMMENTS

OF

ENVIRONMENTAL

LAW

AND

POLICY

CENTER.

PRAIRIE

RIVERS

NETWORK AND SIERRA

CLUB

The remaining issues in this proceeding are narrow, but important. On those issues, two

conclusions emerge from the record.

First, the Board should allow the Illinois Environmental Protection Agency’s proposal to

weaken the cyanide standards to rest in peace. There is no scientific basis for weakening the

standard and no good reason to change Illinois’ cyanide standard at this time.

Second, JEPA’s effort to have the Board ratify the Agency’s 1980s decision to allow more

deoxygenating wastes into Illinois waters than the regulations allow should not be adopted as

proposed. This was clear before the July

25,

2002 hearing. It became even more clear after July 25

when IEPA released reports indicating that large numbers ofIllinois waters are impaired by

discharges of oxygen demanding waste by municipal wastewater plants and other point sources.

The Board should not adopt changes regarding deoxygenating wastes effluent limits without

taking action to assure that any change does not exacerbate Illinois’ serious problem with violations

ofthe dissolved oxygen standard (35 Ill. Adm. Code 302.206) and the standard against offensive

conditions (35 Ill. Adm. Code 302.203).

II.

There is

no valid reason to weaken Illinois’ cyanide standard

During the July 25 hearing, IEPAreconfirmed that no testing has been done that indicates

the effect ofcyanide on Illinois endangered mussels. Further, no testing has been done that would

support the conclusion that two Illinois endangered fish are not at least as sensitive to cyanide as

salmonid species.

1

There has been no testing on any species ofthe same genus as the Blackchin

Shiner and Iowa darter. (Mosher Testimony, July 25 Tr. 27, 30)

1

The pollution sensitive species that IEPA eliminated from the U.S. EPA cyanide criteria calculation to propose its

weaker standard may well serve as proxies for a number of sensitive species that live in Illinois. Indeed, studies cited

by the United States Fish & Wildlife Service indicate that mussels are more sensitive to some pollutants than the

species IEPA decided did not need to be protectedbecause they do not live in Illinois.

1

In its testimony at the July 25 hearing, the Agency offers two newjustifications for its

cyanide proposal. Neither is persuasive.

The Agency Proposal has not been shown to be Conservative

First, in response to the fact that its proposed chronic standard is only a few parts per billion

under the level know to harm a highly valued Illinois species (the Bluegill), IEPA has claimed that

its standard is actually conservative. IEPA argues this is true because the laboratory toxicity tests,

on which the criterion was based, were performed using free cyanide but the proposed standard is

for weak acid dissociable cyanide (“WAD cyanide”), which measures some forms ofcyanide that

are not free.

However, IEPA admits that its standard does not measure total cyanide, which would

include forms ofcyanide compounds that are not measured by the tests for WAD cyanide. (Mosher

Testimony, July 25 Tr. 11) Further, during the hearing it was determined that little is known ofthe

toxicity of cyanide compounds, except that they are less toxic than free cyanide. (Mosher

Testimony, July 25 Tr. 11-12) The circumstances in which the cyanide compounds break down in

the environment to release free cyanide in Illinois waters are also unclear. The 1984 Criteria

document, on which Illinois EPA selectively bases its argument, points out a wide variety ofways

in which cyanide ions can be liberated from complexes by light, low pH or other factors. (pp.2-3)

In short, using WAD cyanide instead offree cyanide is conservative insofar as it includes

forms ofcyanide that are less toxic than the free cyanide that was used in the toxicity tests. Using

WAD cyanide is not conservative, but risky, in that it does not include forms ofcyanide that may

be toxic or that may release free cyanide under other environmental conditions. Whether on balance

using WAD cyanide is more conservative or less conservative is simply unknown.

The Testing Sensitivity Just~fIcationOfferedfor Weakening the Cyanide Standardfails

factually and logically.

IEPA claims that, even if no discharger in Illinois is having any real problemwith cyanide,

adoption of its proposal is neededbecause the WAD method for testing cyanide is not accurate

enough to test to the current 5.2 micrograms per liter standard.2 In its pre-filed testimony, IEPA

claimed there is no approved method that can reliably test at 5.2 micrograms.

However, as presented at the July 25 hearing, there is a US EPA approved method, OIA

—

1677, capable oftesting for cyanide well below the current standard.3 This method is approved for

NPDES permits. 64 Fed. Reg. 73414 (1999)

Predictably, Illinois EPA will now claim that although the U.S. EPA has approved a method

that would allow testing well the level ofthe current standard, Illinois dischargers should not be

2Unfo~ate1y IEPA has also apparently failed to get its facts straight on whether there is a cyanide problem in

Illinois. The Illinois Water Quality Report 2002, issued after the July

25

hearing by JEPA, shows 110 miles of Illinois

streams as impaired by cyanide. (Ex. A)

~

it does not appear that the WAD method used by Illinois EPA has been approved by U.S. EPA.

2

required to use the method because there are no laboratories available. However, there is a long list

of laboratories that can use the new method. (Ex. B)

The fact that there are not more such laboratories is undoubtedly due to the fact that Illinois

and certain other states do not require that OIA

-

1677 be used. Obviously, there will never be

much demand for more sensitive testing as long as states are willing to accept testing less likely to

reveal that a discharger has a problem.

Leaving aside the fact that IEPA is wrong in claiming that sufficiently sensitive testing

methods do not exist, the fact is that lack ofsufficiently sensitive testing is never a good reason for

adopting a weaker standard. IEPA admits as much by admitting that the mercury should not be

changed although IEPA (wrongly) believes that methods are not available to test down to the level

of sensitivity required to measure mercury at the human health standard level. (Mosher Testimony

July 25 Tr.32). See also 40 CFR Pt. 132 App. F Procedure 8 D. (pollutant minimization program

designed for situation where water quality based effluent limit is below the quantification level for

dischargers to the Great Lakes)

Moreover, IEPA’s claim that the cyanide standard should be weakened because sufficiently

sensitive testing methods are unavailable is somewhat disingenuous given that IEPA does not

require testing sufficiently sensitive to catch violations of the current standard.

Under the current

standard,

EPA does not ask dischargers to test more accurately that 10 microgram per liter.

(Mosher Testimony, July 25 Tr. 30) IEPA is asking the Board to change a standard so that TEPA

will not have to require testing to a level ofaccuracy that it already does not require.

Although IEPA should require testing of sufficient accuracy to determine if water quality

standards for mercury, cyanide and other pollutants are being violated when such accurate testing is

available, it does not do so.

III.

IEPA Must Do More to Prevent Violations ofDissolved Oxygen Standards

The Sierra Club,

Prairie

Rivers

Network

and the Environmental Law

and

Policy Center of

the Midwest (“Environmental Groups”)

have not objected to using

a CBOD5

test instead ofa

BOD5 test for determining

whether sewerage treatment plants are

meeting the secondary

treatment

requirements established by Congress decades ago. The federal rule that defines “secondary

treatment” for technology-based limit purposes states that 25 mgfL

CBOD5 may be substituted for

30 mg/L

BOD5, 40 CFR

§

133.102.

The problem is that IEPA’s proposal ratifies its 1980s decision to measure CBOD5 instead

ofBOD5 with regard to discharges covered by 35 Ill. Adm. Code 304.120(b) and (c). These

provisions are the only mechanisms Illinois has established to protect Illinois waters in the situation

in which secondary treatment is not adequate to protect water quality because the effluent makes up

a large percentage ofthe flow or there are multiple pollutionsources. Because by definition

3

CBOD5 is less than all ofthe BOD5, IEPA’s proposal has the effect ofallowing more

deoxygenatingUnder

thewastesCleantoWaterbe

dischargedAct,

dischargesthan

is authorizedofpollutantsunderto

thethenation’scurrentwatersBoard wererules.4to be

eliminated 15 years ago through a progressive tightening’ of effluent limits as technology improved.

33 USC

§

1251(a)(1);

Adler, R.W, Landman, J.C. and Cameron, D.M., The Clean Water Act 20

Year Later, Island Press (1993) p. 137. Now, however, we see the IEPA seeking to further loosen

effluent limits from what was set by the Board almost 30 years ago

(5

mg/L BOD5). From the level

ofsupport for the IEPA’s proposal from the representatives ofpoint source polluters, one must

assume that the sewerage treatment industry has failed to make any technological advances in the

treatment ofdeoxygenating waste in the last three decades.

That JEPA and sewerage treatment agencies are now asking forhigher effluent limits than

the Board established in 1973 is not merely a sad reflection on the industry. The failure to control

deoxygenating waste has had serious impacts on Illinois waters.

A.

Illinois waters now suffer from discharges ofdeoxygenating waste.

This is not the time to loosen controls on discharges of deoxygenating wastes but instead to

find better ways to control these discharges. After the July 25 hearing, Illinois EPA released two

reports indicating that discharges from point sources are causing violations ofIllinois dissolved

oxygen standards. The Illinois Water Quality Report 2002 states that 2962 miles ofthe 15,993

miles ofstreams assessed are impaired potentially because of“Organic Enrichment! LowDissolved

Oxygen” and 80,135 acres ofIllinois lakes are potentially impaired by this cause. (Ex A)5 Although

other sources ofpollution certainly contributed to this problem, the Illinois 303(d) list ofimpaired

waters (htt~://www.epa.state.i1.us/water/watershed/reports/303d-report/2oo2-

report / 303 d

-

report —2002

.

pdf),

also released after the July 25 hearing, plainly indicates that

industrial point sources (Code 100 in source column) and municipal point sources (Code 200) are

playing a role in the low dissolved oxygen impairment ofmanywaters across Illinois including

Maucopin Creek, Lake Springfield, the Des Plaines River, the Fox River, Salt Creek (Du Page), the

East

Branch ofthe Du Page River,

Marion Lake, the Big Muddy River, the Sangamon River, Rend

Lake, Cedar Creek, and Addison Creek. 81 miles ofthe Illinois River are listed as potentially

impaired by “Organic Enrichment/Low Dissolved Oxygen” with the source ofthis pollution listed

as “unknown.” (p.33). Given the level ofmunicipal discharge to the Illinois River, point sources

certainly constitute at least some part ofthe unknown.

The above figures on dissolved oxygen violations understate the problem. Only 18 of

Illinois waters have been monitored. Further, as we have been informed by IEPA, its monitoring

network was established to avoid taking samples near known point sources.

6

~Adoption of the Illinois EPA proposal will not actually loosen the effluent limits as to municipal discharges as the

Agency did that by itself without Board approval in the 1980s.

~The Illinois Water Quality Report 2002 also has separate listings for waters potentially impaired by nutrients. 3082

miles of Illinois streams and 114,903 acres ofIllinois lakes are potentially impaired by these inadequately regulated

pollutants. (Ex. A) Nutrients not only cause violations of the dissolved oxygen standard, but cause algal blooms that

violate Illinois standards against offensive conditions.

6

Naturally, it is not known how many of the impairments listed in Illinois Water Quality Report would be present if

the dissolved oxygen standards were weakened in the manner that the Illinois Association of Wastewater Agencies has

4

B.

Illinois can practically do more to protect its waters against discharges of

deoxygenating wastes.

That so many Illinois waters are impaired at least in part by regulated point sources is not

the result ofuncontrollable forces. Although there is a sizable contribution to BOD from

nitrogenous compounds, EPA admits that it essentially never regulates ammonia discharges to

prevent violations of dissolved oxygen standards. (Mosher Testimony, March 6, 2002, Tr. 34).

Further, Illinois has not performed modeling or taken other steps to assure that authorized

discharges do not cause or contribute to violations ofdissolved oxygen standards for decades.

(Frevert Testimony July 25 Tr.75-6) Other states do so. As explained by the Michigan Department

ofEnvironmental Quality:

Typically, CBOD5 limits are placed in NPDES permits for all facilities which have

the potential to contribute significant quantities ofoxygen consuming substances to

waters ofthe state. These limits are developed in direct correlation with limits for

ammonia nitrogen and dissolved oxygen.

In determining CBOD5 limits, stream modelers use computer models which

simulate actual stream conditions. Model inputs include the flow ofthe receiving

stream, the quantity of water to be discharged, the decay rate forthe particular type

ofwastewater, the stream’s slope, and temperature. Other upstream or downstream

dischargers are also considered in the model. The modeler determines maximum

limits for CBOD5 and ammonia nitrogen and minimum limits for dissolved oxygen.

These limits are selected to insure that Water Quality Standards for dissolved

oxygenThe

onlyarestepsmetthatin

theIllinoisreceivingtakeswater.to

protect(Ex.C)against7

violations of dissolved oxygen standards

are the provisions ofSection 304.120 (b), which requires effluent limits of20 mg/L BOD5 if a

discharger has an untreated waste load of 10,000 population units or more, and Section 304.120(c),

which generally requires limits of 10 mg/L BOD5 if the dilution ratio is less than five to one. The

Environmental Groups continue to believe that these provisions should not be weakened.

What is really needed are rules that require use ofmodeling or other means to assure that

permits are not issued that allow discharges that cause or contribute to violations ofdissolved

oxygen standards. At a minimum, if “CBOD5” is substituted for

“BOD5”,

adjustments should be

made that recognize that CBOD5 does not make up all ofBOD5.

suggested. However, until the IAWA makes a proposal for new standards and proves their scientificvalidity, the

Board certainly cannot make decisions based on the standards that IAWA wishes existed.

~ It is claimed that Illinois now approaches this problem through use of total maximum daily load studies, but IEPA

has never completed a TMDL. (Frevert Testimony July 25 Tr.76) Even ifIEPA actually did TMDLs, this would not be

an acceptable approach because TMDLs are never attempted in Illinois until an impairment is found. Perhaps naively,

we would like to prevent impairments from occurring in the first place.

5

This is particularly the case as to Section 304.120(b). The Board on numerous occasions has

recognized that CBOD5 limits well below 20 mg/L are readily attainable by almost all dischargers.

See Post Hearing Comments ofELPC, PRN and Sierra Club, filed 4-12-02, p. 8 fn. 12.

At the July

25,

2002 hearing, Mr. Callahan, spokesman for the Illinois Association of

Wastewater Agencies, addressed his testimony made in the March hearing that effluents at the 10

mg/L CBOD5 level are “readily attainable

...

with moderately appropriate user fees and citizens

tax rates” (March Tr. 131), and implied that he had somehow been misquoted. Mr. Callahan

protested that “I am not on the record intentionally ofindicating that a secondary treatment process

can consistently produce a 10 milligram per liter BOD.” (Callahan testimony, July 25 Tr. 43).

Mr. Callahan is correct that he is not on the record as saying a secondary treatment plant can

meet a 10 mg/L BOD standard but then no one said he did. For purposes ofthis proceeding, no one

should care if he ever said that or not. The critical question for the Illinois environment is what can

be done at an economically reasonable expense to address Illinois’s dissolved oxygen problems

(and offensive conditions, as defined by 35 Ill. Adm.302.203, caused by point source discharges).

On that question, Mr. Callahan’s March testimony and numerous other authorities agree that there

is no reason to allow effluents as bad a 20 mg/L CBOD5 if there is any risk that the discharge will

cause or contribute to violations ofIllinois water quality standards. An effluent of 10 mg/L

CBOD5 is readily attainment at a reasonable cost.

CONCLUSION

Consideration ofchanges to Illinois cyanide standard should be left until such time as there

is more information on the potential effects of cyanide on rare Illinois mussels and other

endangered species.

IEPA’s proposal regarding effluent limits fordeoxygenating wastes should be adopted as to

technology-based requirement of35 Ill. Adm. Code 304.120(a). However, the Board should take

action to assure that changes to Illinois regulations are not made that will increase the impairments

to Illinois waters caused by discharges ofdeoxygenating wastes. EPA should be required to use

modeling or other means to analyze the total effect ofdischarges on dissolved oxygen levels.

Alternatively, as has been proposed by the Environmental Groups in the past, the Board should

moderate the effect ofEPA’s proposal by recognizing that CBOD5 BOD5. Lower CBOD5

figures should be used when substituting for BOD5.

Albert F. Ettinger (ARM~C# 3125045)

Counselfor Environmental Law & Policy

Center, Prairie Rivers Network and Sierra Club

6

6

Illinois

Environmental

Protection Agency

m~

AfROW/02-1106

Bureau ofWater

P.O. Box 19276

Springfield, IL 62794-9276

July2002

Illinois Water Quality Report

2002

Back to top

Iffinois Environmental Protection Agency

Back to top

Bureau of Water

EXHIBIT A

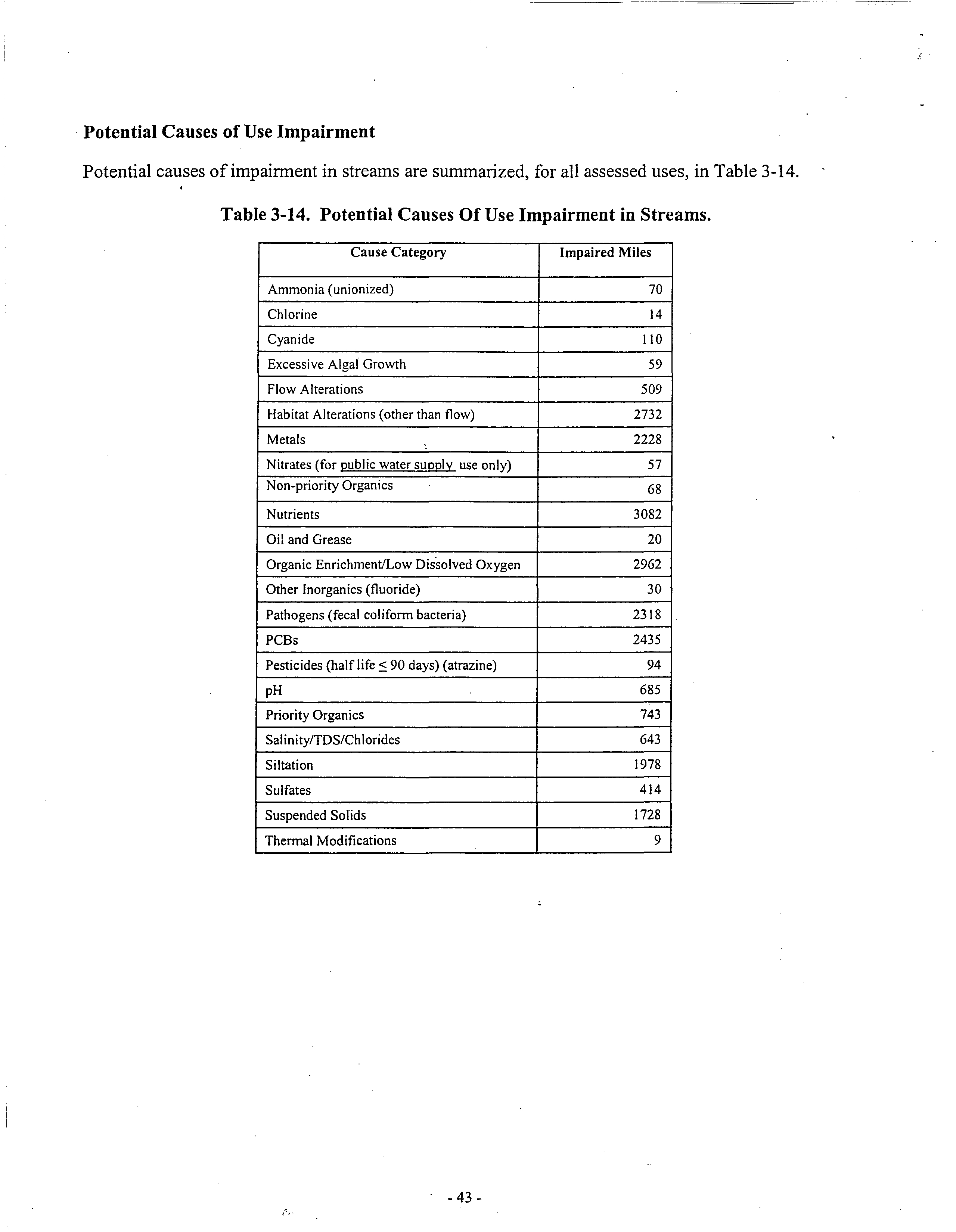

~Potential Causes of Use Impairment

Potential causes ofimpairment in streams are summarized, for all assessed uses, in Table 3-14.

Table 3-14. Potential Causes Of Use Impairment in Streams.

Cause Category

Impaired Miles

Ammonia (unionized)

70

Chlorine

14

Cyanide

110

Excessive Algal Growth

59

Flow Alterations

509

Habitat Alterations (other than flow)

2732

Metals

2228

Nitrates (for public water supply use only)

57

Non-priority Organics

‘

68

Nutrients

3082

Oil and Grease

20

Organic Enrichment/Low Dissolved Oxygen

2962

Other Inorganics (fluoride)

30

Pathogens (fecal coliform bacteria)

2318

PCBs

2435

Pesticides (half life ~ 90 days) (atrazine)

94

pH

‘

685

Priority Organics

743

Salinity/TDS/Chlorides

643

Siltation

1978

Sulfates

414

Suspended Solids

1728

Thermal Modifications

9

-43-

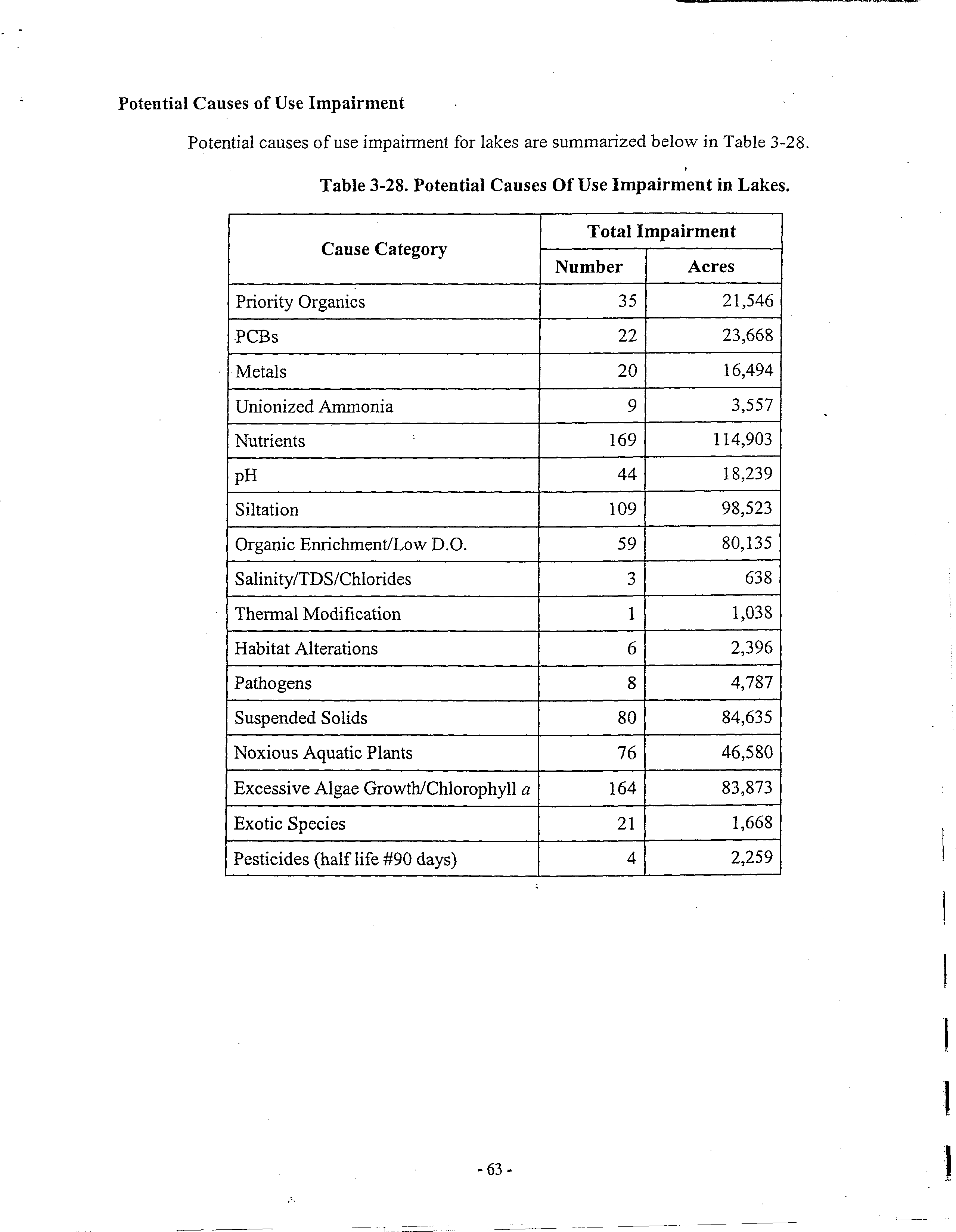

Potential Causes of Use Impairment

Potential causes ofuse impairment for lakes are summarized below in Table 3-28.

Table 3-28. Potential Causes Of

Use Impairment in Lakes.

Cause Category

Total Impairment

Number

Acres

Priority Organics

35

21,546

•PCBs

22

23,668

Metals

20

16,494

Unionized Ammonia

9

3,557

Nutrients

169

114,903

pH

44

18,239

Siltation

109

98,523

Organic Enrichment/Low D.O.

59

80,135

Salinity/TDS/Chlorides

3

638

Thermal Modification

1

1,038

Habitat Alterations

6

2,396

Pathogens

8

4,787

Suspended Solids

80

84,635

Noxious Aquatic Plants

76

46,580

Excessive Algae GrowthlChlorophyll

a

164

83,873

Exotic Species

21

1,668

Pesticides (half life ~90 days)

4

2,259

1

-

63

-

I

AUG ~1 ‘~217:31 FR SCC—SAMFLE CONTROL CE 7034618056 TO 13127953730

P. 02/03

Laboratories Capable

of

Perforrnin~tMethod 1677 Analysis

These laboratories are identified below for informational purposes only. This does

not

representan

exhaustive list, nor does it constitute endorsement by either EPA

or

DynCorp ofany laboratory appearing

on the list.

Analytical Services Laboratory, Inc.

1988

Triumph St.

Vancouver,

B.C.,

Canada VSL1KS

Contact: Blair Easton

Phone: (604) 253-4188

Bayer Environmental Testing Services

StateRoute 2 North,

P.O. Box

500

New Martinsville, WV

26155

Contact: John Sebroskie

Phone: (304) 455-4400

Fax: (304)

455-5134

DegussaCorporation

4

Pearl Ct.

Allendale, NJ 07401

Contact: JagChattopadhyay

Phone: (201) 818-3700

DeltaFaucetCompany

Chemistry Laboratory

Address Unknown

Contact: Mike Mosely

Phone: (812) 663-4433

Frontier (3eoscienccs.

414 Pontius North, SuiteB

Seattle,

WA 98109

Contact: Nicolas Bloom

Phone: (206) 622-6960

Fax: (206)

622-6870

Email: nicolasb@frontier.wa.com

Golden SunlightMines

453 MT Hwy. 2 East

Whitehall, MT

59759

Contact:

Neil Gallagher

Phone: (406)287-3257

Newmont Exploration Limited

Metallurgical Services

412

Wakara

Way, Suite 210

Salt Lake City,UT 84108

Contact: Tom Patten

EXHIBIT B

AUG 01 ‘02 17:31 FR SCC—SAMPLE CONTROL CE 7034618056 TO 13127953730

P.03/03

Phone: (801) 583-8974

01 Analytical

1556 Spring Street

Saint Helena, CA 94574

Contact:

Mike

Straka

Phone: (707)963-1069

Fax: (707) 963-3335

Email: mstraka~’oico.com

University ofNebraska

Department of Chemical Engineering

Beadle Center

Lincoln, NE 68588-0668

Contact: Dr. Ljiljana Solujic

Phone: (402)472-4784

University of Nevada

-

Reno

Department ofChemical

and

Metallurgical Engineering

Mackay School of

Mines/MS

168

Reno, NV 89557

No contact

name

or phone

number

(previous contact is Dr. Solujic atUniversity ofNebraska)

**

TOTAL PAGE.03

**

Biochemical Oxygen Demand

Page 1 of3

State of Michigan_____

D~U

=

F

—

Department of EnvironmentalQuality

Surface Water Quality Division

Permits Section

Biochemical Oxygen Demand (BOD)

Biochemical Oxygen Demand, or BOD, is a measure of the quantity of

oxygen consumed by

microorganisms during the decomposition of organic matter. BOD is the most commonly used

parameter for determining the oxygen demand on the receiving water of a municipal or

industrial discharge. BOD can also be used to ~valuate the efficiency of treatment processes,

and is an indirect measure of biodegradable organic compounds in water.

Imagine a leaf falling into a stream. The leaf, which is composed of organic matter, is readily

degraded by a variety of microorganisms inhabiting the stream. Aerobic (oxygen requiring)

bacteria and fungi use oxygen as they break down the components of the leaf into simpler, more

stable end products such as carbon dioxide, water, phosphate and nitrate. As oxygen is

consumed by the organisms, the level of dissolved oxygen in the stream begins to decrease

Water can hold only a limited supply of dissolved oxygen and it comes from only two sources-

diffusion from the atmosphere at the air/water interface, and as a byproduct of photosynthesis.

Photosynthetic organisms, such as plants and algae, produce oxygen when there is a sufficient

light source. During times of insufficient light, these same organisms consume oxygen. These

organisms are responsible for the diurnal (daily) cycle of dissolved oxygen levels in lakes and

streams.

If elevated levels of BOD lower the concentration of dissolved oxygen in a water body, there is a

potential for profound effects on the water body itself, and the resident aquatic life. When the

dissolved oxygen concentration falls below 5 milligrams per liter (mg/I), species intolerant of low

oxygen levels become stressed. The lower the oxygen concentration, the greater the stress.

Eventually, species sensitive to low dissolved oxygen levels are replaced by species that are

more tolerant of adverse conditions, significantly reducing the diversity of aquatic life in a given

body of water. If dissolved oxygen levels fall below 2 mg/I for more than even a few hours, fish

kills can result. At levels below 1 mg/I, anaerobic bacteria (which live in habitats devoid of

oxygen) replace the aerobic bacteria. As the anaerobic bacteria break down organic matter, foul-

smelling hydrogen sulfide can be produced.

BOD is typically divided into two parts- carbonaceous oxygen demand and nitrogenous oxygen

demand. Carbonaceous biochemical oxygen demand (CBOD) is the result of the breakdown of

organic molecules such a cellulose and sugars into carbon dioxide and water. Nitrogenous

oxygen demand is the result of the breakdown of proteins. Proteins contain sugars linked to

nitrogen. After the nitrogen is “broken off” a sugar molecule, it is usually in the form of

ammonia, which is readily converted to nitrate in the environment. The conversion of ammonia

liup

::

\\

\V\VdC~1.St~tlt..flii.USi’S\\ q’penhl

its/1)aralllCtCrs/bod.htlll

EXHIBIT C

2/19/02

Biochemical Oxygen Demand

Page 2 of

3

to nitrate requires more than four times the amount of oxygen as the conversion of an equal

amount of sugar to carbon dioxide and water.

When nutrients such as nitrate and phosphate are released into the water, growth of aquatic

plants is stimulated. Eventually, the increase in plant growth leads~toan increase in plant decay

and a greater “swing” in the diurnal dissolved oxygen level. The result is an increase in microbial

populations, higher levels of BOD, and increased oxygen demand from the photosynthetic

organisms during the dark hours. This results in a reduction in dissolved oxygen concentrations,

especially during the early morning hours just before dawn.

In addition to natural sources of BOD, such as leaf fall from vegetation near the water’s edge,

aquatic plants, and drainage from organically rich areas like swamps and bogs, there are also

anthropogenic (human) sources of organic matter. If these sources have identifiable points of

discharge, they are called point sources. The major point sources, which may contribute high

levels of BOD, include wastewater treatment facilities, pulp and paper mills, and meat and food

processing plants.

Organic matter also comes from sources that are not easily identifiable, known as nonpoint

sources. Typical nonpoint sources include agricultural runoff, urban runoff, and livestock

operations. Both point and nonpoint sources can contribute significantly to the oxygen demand

in a lake or stream if not properly regulated and controlled.

Performing the test for BOD requires significant time and commitment for preparation and

analysis. The entire process requires five days, with data collection and evaluation occurring on

the last day. Samples are initially seeded with microorganisms and saturated with oxygen

(Some samples, such as those from sanitary wastewater treatment plants, contain natural

populations of microorganisms and do not need to be seeded.). The sample is placed in an

environment suitable for bacterial growth (an incubator at

200

Celsius with no light source to

eliminate the possibility of photosynthesis). Conditions are designed so that oxygen will be

consumed by the microorganisms. Quality controls, standards and dilutions are also run to test

for accuracy and precision. The difference in initial DO readings (prior to incubation) and final

DO readings (after 5 days of incubation) is used to determine the initial BOD concentration of

the sample. This is referred to as a BOD5 measurement. Similarly, carbonaceous biochemical

oxygen test performed using a 5-day incubation is referred to as a CBOD5 test.

Water Quality Standards for BOD

Although there are no Michigan Water Quality Standards pertaining directly to BaD, effluent

limitations for BOD must be restrictive enough to insure that the receiving water will meet

Michigan Water Quality Standards for dissolved oxygen.

Rule 64 of the Michigan Water Quality Standards (Part 4 of Act 451) includes minimum

concentrations of dissolved oxygen that must be met in surface waters of the state. This rule

states that surface waters designated as coldwater fisheries must meet a minimum dissolved

oxygen standard of 7 mg/I, while surface waters protected for warmwater fish and aquatic life

must meet a minimum dissolved oxygen standard of 5 mg/I.

Biochemical Oxygen Demand Limitations in NPDES Permits

Typically, CBOD5 limits are placed in NPDES permits for all facilities which have the potential to

contribute significant quantities of oxygen consuming substances to waters of the state. These

limits are developed in direct correlation with limits for ammonia nitrogen and dissolved oxygen.

The nitrogenous oxygen demand is computed separately because of the difference in oxygen

demand (as explained above) and because the rate of oxygen consumption over time varies

hip \\ ~ \\

.dL’q.st~iIc.Ih1I.us.swqiperniits/puranic1ers/bod.ht~n

2/19/02

Biochemical Oxygen Demand

Page 3 of3

from carbonaceous oxygen demand. Ammonia is further considered separately because in

sufficient levels (dependant upon several variables) it can also be toxic to living organisms.

In determining CBOD5 limits, stream modelers use computer models which simulate actual

stream conditions. Model inputs include the flow of the receiving stream, the quantity of water

to be discharged, the decay rate for the particular type of wastewater, the stream’s slope, and

temperature. Other upstream or downstream dischargers are also considered in the model. The

modeler determines maximum limits for CBOD5 and ammonia nitrogen and minimum limits for

dissolved oxygen. These limits are selected to insure that Water Quality Standards for dissolved

oxygen are met in the receiving water.

Permit-related questions and comments? Contact Fred Cowles, cowlesf(~michigan.gov

Web page maintained by Sean Syts, sytss(ä~michician.gov

Last revision: April 30, 2001

http ://www.deq .state.mi. us/swq/permits/parameters/bod . html

11 ~ w~

Idea I

I

~

I

Home

littp ://www.deq state. ml.us/swq/pcrm I is/parameters/bod. htm

2/19/02

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I, Albert F. Ettinger, certify that I have filed the above Notice ofFiling together with an

original and 9 copies ofthe Post-Second Hearing Comments of Environmental Law and Policy

Center, Prairie Rivers Network and Sierra Club, on recycled paper, with the Illinois Pollution

Control Board, James R. Thompson Center, 100 West Randolph, Suite 11-500, Chicago, IL

60601, and served all the parties on the attached Service List by depositing a copy in a properly

addressed, sealed envelope with the U.S. Post Office, Chicago, Illinois, with proper postage

prepaid on September 6, 2002.

Albert F. Ettinler

Albert F. Ettinger, Senior Attorney

Environmental Law and Policy Center

35

East Wacker Drive, Suite 1300

Chicago, IL 60601

SERVICE LIST

Mike Callahan

Bloomington Normal Water Reclamation District

P.O. Box 3307

Bloomington, IL 61702

Larry Cox

Downers Grove Sanitary District

2710 Curtiss Street

Downers Grove, IL 60515

Dennis Daffield

Department ofPublic Works

City of Joliet

921 East Washington Street

Joliet, IL 60433

Lisa M. Frede

Chemical Industry Council

9801 West Higgins Road

Suite

515

Rosemont, IL 60018

James T. Harrington

Ross

& Hardies

150 North Michigan, Suite 2500

Chicago,

IL 60601

Roy M. Harsch

Gardner, Carton & Douglas

321 N Clark Street

—

Suite 3400

Chicago,

IL 60610

Ron Hill

Metropolitan Water Reclamation District

100 East Erie

Chicago, IL 60611

Katherine Hodge

Hodge Dwyer Zeman

3150 Roland Avenue

P.O. Box 5776

Springfield, IL 62705-5776

Margaret P. Howard

Hedinger & Howard

1225 South Sixth Street

Springfield, IL 62703

Robert A. Messina

Illinois Environmental Regulatory Group

215 East Adams Street

Springfield, IL 62701

Tom Muth

Fox Metro Water Reclamation District

682 State Route 31

Oswego, IL 60543

Irwin Polls

Metropolitan Water Reclamation District ofChicago

6001 West

Cicero, IL 60804

Sanjay Sofat

Illinois Environmental Protection Agency

1021 North Grand Avenue East

Springfield, IL 62794-9276

Marie Tipsord

Attorney,

Pollution Control Board

100 West Randolph Street, 11-500

Chicago, IL 60601k