IN THE MATTER OF:

WATER QUALITY AMENDMENTS TO

35

III. Adm. Code 302.208(e)-(g),

302.504(a),

302.575(d), 303.444, 309.141(h);

and

PROPOSED 35

III. Adm. Code 301.267,

301.313,

301.413, 304.120, and 309.157

R02-11

(Rulemaking

-

Water)

CL~K’~

~PPfe~

Ji~N

22

20U2

STATE OP

IWNOJS

Pollution

Control

Board

NOTICE OF FILING

Dorothy Gunn,

Clerk

Pollution Control Board

100 West Randolph Street

Suite 11-500

Chicago,

Illinois 60601

Mathew Dunn

Illinois Attorney General’s Office

Environmental

Control Division

James

R. Thompson Center

100 West Randolph Street

Chicago,

Illinois

60601

Marie

E. Tipsord

Illinois Pollution Control Board

James

R. Thompson Center

100 West Randolph Street, Suite 11-500

Chicago,

Illinois 60601

Legal Service

Illinois Department of Natural Resources

524 South Second Street

Springfield,

Illinois 62701-1787

PLEASE

TAKE NOTICE that

I

have today filed with the Office of the

Clerk of the

Pollution

Control

Board the

WRITTEN TESTIMONY OF ROBERT MOSHER, CLARK OLSON, AND

ALAN

KELLER

of the

Illinois Environmental Protection Agency, a

copy of which is herewith

served upon you.

ILLINOIS ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY

Assistant Counsel

Division of Legal Counsel

Dated:

January

18,

2002

Illinois

Environmental Protection Agency

1021 North Grand Avenue East

Springfield,

Illinois 62794-9276

(217) 782-5544

BEFORE THE

ILLINOIS ~

BOARD

)

)

)

)

)

THIS FILING PRINTED ON RECYCLED PAPER

RECEIVED

CLERR’S

OFF’~

BEFORE THE ILLINOIS POLLUTION CONTROL BOARD

J~N

2 22002

STATE OF

ILLINOIS

Pollution

Control Board

IN

THE MATTER OF:

WATER QUALITY AMENDMENTS TO

)

35

III. Adm. Code 302.208(e)-(g),

302.504(a),

)

R02-1

1

302.575(d), 303.444, 309.141(h); and

)

(Rulemaking -Water)

PROPOSED 35

Ill. Adm.

Code 301.267,

)

301 .31 3, 301.413, 304.120,

and 309.157

)

TESTIMONY OF ROBERT MOSHER

QUALIFICATIONS/INTRODUCTION

My name is Robert Mosher and

I am the Manager of the Water Quality Standards

Section within the Division of Water Pollution Control at the

Illinois Environmental

Protection Agency (“Illinois EPA” or “IEPA”).

I have been with

the

Illinois

EPA in excess of

16 years.

Almost all of that time has been spent in my current capacity where my primary

responsibility is the development and implementation of water quality standards.

I

have a

Masters Degree in Zoology from

Eastern Illinois

University where

I specialized

in stream

ecology.

My testimony will cover three topics.

First,

I will

discuss the background

information concerning development of the instant proposal before the

Illinois

Pollution

Control Board (“IPCB” or “Board”).

Second,

I will provide a brief discussion on the

concepts

contained in various sections of the

Illinois EPA’s proposal.

Third,

I will discuss

the

Illinois EPA’s plans for successful implementation of this proposal.

BACKGROUND

INFORMATION

The Federal Water Pollution Control Act Amendments of 1972, 33 U.S.C. §~1251-

1387,

is commonly known as the Clean WaterAct (“CWA”).

Pursuant to the CWA,

states

2

are required to revise and update their water quality standards to ensure thatthey are

protective of public health and welfare, enhance the quality of water and promote the

purposes of the CWA.

33 U.S.C. §1313(c)(2)(A).

The process of reviewing the state’s

standards is called the triennial water quality standards review.

The changes to the water

quality and effluent standards

in the instant proposal are one element of Illinois EPA’s

current triennial review of water quality standards.

In September 2000, the Agency shared a

packet of information concerning this

rulemaking with a number of stakeholders involved

in water quality standards

affairs.

These entities included municipal and industrial

dischargers, environmentalists and other

governmental agencies.

A few helpful comments were received and were employed to

clarify the intent of this proposal.

There were

no adverse comments, and generally

speaking, the changes to the

Board regulations that encompass this proposal should- not

be controversial since they represent the current state-of-the-art

in water quality standards.

The CLI rulemaking (R97-25) introduced

Illinois stakeholders to several ofthe

concepts

leading to the new and revised standards for the General Use waters proposed

here.

The

instant rulemaking is the result of careful consideration regarding the appropriateness of

selected aspects of the GLI for General

Use waters of the state.

ILLINOIS

EPA’S PROPOSAL

This proposal is divided into five

parts.

Part I proposes adoption of new aquatic life

acute and chronic water quality standards for benzene, ethyl benzene, toluene, and

xylene(s) (“BETX”) for both General

Use waters and the

Lake

Michigan

Basin.

Part II

contains revised acute and chronic water quality standards for zinc, nickel, and weak acid

dissociable cyanide.

Part III proposes that most General

Use metals water quality

3

standards

be specified

in terms of dissolved concentration rather the total concentration

used in

the existing standards.

Part IV contains corrections to the GLI regulations at 35

III.

Adm. Code 302.504(a), 302.575(d), and 309.141.

Part V proposes to update the Board

regulations at 304.120 to reflect that the carbonaceous component of BOD5 be regulated

in treated domestic waste effluents.

I will cover the first four Parts of the

Illinois

EPA’s

proposal and Al

Keller,

Manager of the Agency’s Northern Municipal Permit Unit will testify

to Part V of the proposal.

Part

I:

We intend for all the newly derived standards to either replace existing

General

Use standards or to be added as new listed substances under 35 IAC 302.208(e)

and

(f).

Each substance addressed has both an acute and

a chronic value

proposed.

The

regulatory constructs in 302.208 (a) through

(d) will

apply to newly added or revised

standards.

Several new STORET numbers are necessary because many metals

standards are now proposed to be

in the dissolved rather than total form.

Standards to

protect aquatic life for BETX substances will

also be inserted into the Lake

Michigan Basin

water quality standards where none now exist.

For the

Lake Michigan

Basin, these

standards will be based

on sensitive species from both cold and warm water.

Additionally,

benzene will have a General Use human health standard inserted at 302.208(f) identical to

the

Lake

Michigan

Basin human health standard that already exists.

Part II:

A goal of the triennial review of standards that led to this proposed

rulemaking before the

Board was to update general use water quality standards for toxic

metals found at 35 IAC 302.208(g).

These metals have “one

number” standards

adopted

in the

1970’s as opposed to

“two

number” acute and chronic standards that have been the

preferred method of adopting standards

for the

last

15 years or so.

Nickel and zinc fall

into this category.

Selenium and silver are also considered to be significantly toxic metals

4

and still exist as one number standards in 302.208(g).

New standards for selenium and

silver are not proposed at this time because debate is still ongoing about just how

standards for these metals should

be derived.

USEPA is pursuing these issues and when

a consensus is reached at the national level, IEPA will propose updated standards for

these metals.

National consensus had not been achieved

at the time the Agency filed

its

petition with the

IPCB.

Part III:

The national consensus indicates that the dissolved form of metals

is the

toxic component to aquatic organisms.

It is widely believed that filterable metals are likely

to be complexed with other water constituents and will

have little toxic influence.

For this

reason, GLI water quality standards

for metals were adopted in dissolved form and the

Agency’s petition in this matter lists metals water quality standards as dissolved metal.

Since most researchers

reported total metals when relating the concentrations that

organisms were exposed to in toxicity tests,

USEPA did some experimentation to

determine the percentage of these reported concentrations that was actually dissolved

metal.

The result of this endeavor was a table of metals conversion factors.

These were

published by USEPA under the GLI.

For example, if the final acute value for a given metal

in the total form

is 2.0 mg/L and the conversion factor is

0.8, as determined from

measuring total vs. dissolved metal under the conditions of laboratory toxicity tests, then

the dissolved metal final acute value

is 1.6

mg/L.

The proposed water quality standards

have been converted to dissolved metal concentrations through the

use of the stated

conversion factor.

The BETX substances have no such toxicity relationship between dissolved

and

suspended components.

The total form is presently considered to be that which should be

regulated.

Our proposal designates total BETX substances as the water quality

5

standards.

Federal

regulations at 40 CFR 122.45 require that NPDES permit limits for

metals

be established as total measurable metal.

When water quality based effluent limits

(WQBELs)

are required

in

a permit, this would mean converting the dissolved

metal water

quality standard value

into a total metal value.

A translator factor

is

used for this purpose

and,

in the absence of site-specific data concerning the

ratio of total to dissolved

metal,

consists simply of the

reciprocal of the conversion factor.

This means that if a mixing zone

is not involved

in a WQBEL, the total metal limit would

be what the water quality standard

would have been in the “total metal” form.

That is,

the differential between total and

dissolved

metals in the toxicity tests would not be factored out.

We have

included a site-

specific metals translator provision

in the

proposed

IPCB regulations.

This would allow

dischargers to measure the

ratio of dissolved to total metal

in their effluent and thereby

apply to the Agency for establishment of total metal WQBELs based on this effluent

specific relationship.

Effluents will therefore essentially be regulated

on their potential to

discharge dissolved metals at levels consistent with the water quality standards yet within

the

bounds of the -total metals effluent standards at 35

III. Adm. Code Part 304.

At this time recalculated standards are not being proposed for six metals, arsenic,

cadmium, copper,

lead, mercury and trivalent chromium, found at 35

Ill. Adm.

Code

302.208(e).

Lead and mercury standards

were updated in

1996, there has been no

indication that the arsenic, copper and trivalent chromium

standards are in

need of

revision and cadmium is currently under federal review.

However,

it is appropriate to

convert these standards to the dissolved form to conform to USEPA guidance.

This

simply involves the

application of the correct conversion factor.

The other substances in

302.208(e) are not amenable to regulation

in the dissolved form.

TRC (total residual

6

chlorine) is by nature an inclusive parameter.

Hexavalent

chromium standards

were

adopted as total metal

in the

Board’s CLI rulemaking.

It may be best to continue to

regulate this substance in the total metal form.

Part IV:

Additionally, we propose several corrections to recently adopted Board

regulations.

The GLI rulemaking intended to list metals standards

in the dissolved form.

The conversion factors that accomplish this were inadvertently left out, however.

We now

correct this mistake by inserting the proper conversion factors into 35

III. Adm. Code

302.504(a).

Section 302.575 was missing several pieces of essential information that we

also now correct.

35

III. Adm. Code 303.444

is a site-specific regulation that is no longer

pertinent given the changes to the General

Use cyanide standards and therefore we

propose that the

Board delete this regulation.

We are also proposing to replace language

at 35 III. Adm.

Code 309.141(h)(3) with

a more accurate instruction for implementing the

metals translator in NPDES permits.

ILLINOIS EPA’S FUTURE PLANS

The proposed changes to the standards give rise to several issues regarding the

implementation of water quality standards in NPDES permits and

in other Agency

programs.

The Illinois

EPA intends to provide the

Board a draft Agency rule for

implementing water quality based effluent limits at hearing under R02-1 1.

This rule will

later pass through the JCAR approval process before becoming finalized.

The Agency

rule will allow the

Board and stakeholders to envision how the new Board water quality

standards will

be implemented in the day-to-day activities of the Agency.

7

This concludes my pre-filed testimony.

I will

be supplementing this testimony as needed

during the hearing.

I would be happy to address any questions.

January 29, 2002

Illinois Environmental Protection Agency

1021 North Grand Avenue

East

P.O. Box 19276

Springfield,

Illinois 62794-9276

By:

Robert Mosher

THIS FILING PRINTED ON RECYCLED PAPER

8

CL!RK’~

OP~ICE

BEFORE THE

ILLINOIS POLLUTION CONTROL BOARD

JAN

2.2

2002

STAT~

OF ILLINOIS

PollutIon Control

Board

IN

THE MATTER OF:

WATER QUALITY AMENDMENTS TO

)

35

III. Adm. Code

302.208(e)-(g), 302.504(a),

)

R02-1 I

302.575(d),

303.444, 309.141(h); and

)

(Rulemaking

-

Water)

PROPOSED 35

III. Adm. Code 301 .267,

)

301.313, 301.413, 304.120, and 309.157

)

TESTIMONY OF CLARK OLSON

QUALIFICATIONS/INTRODUCTION

My name

is Clark Olson and

I have

been employed by the

Illinois

Environmental

Protection Agency (“Illinois EPA” or “Agency”) for over 20 years.

I work in the Water

Quality Standards Unit of the

Division of Water Pollution Control as a toxicologist.

I have

been involved with water quality standards

issues throughout my career with the Agency

and have participated

in several previous rulemakings of this type.

I

have

a

PhD in

Biology from

University of Miami (Florida) and have done postdoctoral research

in

toxicology at North Carolina State University.

My testimony will

discuss the development

process of the instant proposal before the

Illinois Pollution Control Board (“IPCB” or

“Board”).

DEVELOPMENT PROCESS

Early in the year 2000,

I began to gather toxicity data for the

instant proposal.

I

developed numeric values suitable for water quality standards for several substances

using USEPA sanctioned methods.

New aquatic life acute and chronic standards were

derived for benzene, ethyl benzene, toluene and xylenes (“BETX”) for both General

Use

9

and Lake Michigan

Basin waters and human health standards were developed for General

Use waters.

New

General Use aquatic life acute and chronic standards were derived for

zinc, nickel and weak acid dissociable cyanide. There are presently single number

standards for zinc and nickel for General

Use waters and current practice recommends

acute and chronic numbers.

In general,

I followed the procedure

laid down

by USEPA in the

Guidelines for

Deriving Numerical National Water Quality Criteria for the Protection ofAquatic Organisms

and Their Uses,

(“the Guidelines”)

1985 (NTIS PB85-227049) which have been followed

in

standards’ development by the USEPA and by other states.

These guidelines have also

been used as a basis of the procedures in

35 III. Adm.

Code Part 302 Subpart E and

Subpart F for deriving water quality criteria.

In the full

USEPA method, often

referred to as “Tier I”, the minimum database

consists of toxicity data for representatives of 8 (reduced to 5

in Subpart F) different

groups of animals.

A statistical procedure then finds the ~

percentile of the distribution of

the data.

That is,

95

of the organisms are considered less sensitive than the one(s) at

the 5th

percentile level. For the acute criterion, this number is divided by 2, and in the

chronic criterion

it is used as is.

However, the chronic criterion

is often derived

by using

an

acute to chronic ratio (“ACR”) obtained from data for several species when

adequate

chronic tests are not available for all the specified groups of organisms.

In the

proposed

standards

presented here, the quality of the databases available does

not always allow

use of the Tier

I procedure for all substances and so a default (“Tier

II”) procedure is used.

The Guidelines process involves several steps.

First, data for each substance was

obtained from the USEPA AQU IRE database and any other sources that were found

coincidentally.

USEPA Ambient Water Quality Criterion documents and Great Lakes

10

Water Quality Standards Initiative documents were also consulted for all substances.

Second, the data was tabulated as directed by the Guidelines.

Third,

much of the original

literature (mostly journal articles) where the original data was

presented was obtained from

our library or other libraries, so that the data could

be verified.

This was especially

necessary for the data for the most sensitive species since this data

is most important in

determining the actual value of the

criterion.

Fourth, statistical calculations were made by

use of a spreadsheet according to the equations

in the

Guidelines.

Finally,

documents

were prepared for each of the substances and are part of the

package submitted.

With the exception of the BETX parameters, the standards for the substances in

this rulemaking are to apply only to General

Use waters.

Therefore,

I used data from only

warm-water organisms in

the derivations for zinc, nickel and cyanide standards.

Trout,

salmon and other cold-water species were

included

in the development of the BETX

standards

for the

Lake Michigan

Basin,

but not for General Use waters,

because these

species do not occur in

Illinois waters outside of Lake Michigan.

Additionally, only species

with

reproducing wild populations in the

Midwest were

utilized

in the derivations.

Metals that have toxicity influenced by water hardness have standards expressed

as an equation containing a factor for slope for the hardness relationship.

Slope values for

nickel and

zinc in our proposed standards are the same values as found

in the

most

recent national criteria documents for GLI standards.

Given that all these substances had

a large database of toxicity test results when the national criteria were

published,

the

additional tests

I found should have very little

impact on the slope value and we therefore

saw

no need to change them.

Of all the substances considered

in this rulemaking, only benzene is believed to

have significant human health effects

—

cancer

-

such that a separate human health

11

standard

is necessary since such standards are lower than those necessary to protect

aquatic life.

I reported human health criteria for the other BETX substances under the

individual summaries for the purpose of demonstrating that these values are much higher

than

the standards

protective of aquatic life.

The metals likewise are not harmful to

humans at the concentrations regulated for aquatic life.

The Human health standard for

benzene is the same as the

Lake

Michigan standard

in 302.504(a).

There are currently acute and chronic General

Use standards under the weak acid

dissociable cyanide form.

The reason they are being readdressed stems from the fact that

they were taken directly from USEPA national criteria

document, which means that cold-

waterspecies such as trout and salmon were

used

in the criteria derivation.

Since

General

Use waters are virtually all warm water habitats, these standards have come

under scrutiny.

The Metropolitan Water Reclamation

District of Greater Chicago obtained

site-specific relief from the

IPCB several years ago for weak acid dissociable cyanide

based on the

premise that warm water species were not as sensitive.

The site-specific

standards they obtained are very similar to the values we propose.

The R88-21

rulemaking (“Toxics”) recognized that total cyanide was not

representative of the toxic component of this substance.

Total cyanide laboratory analysis

measures complexed forms of cyanide, such as some ofthe iron-cyanide compounds that

are known to be nontoxic.

Free cyanide

is a

rough equivalent of dissolved metals, but

unfortunately free cyanide is difficult to measure and other, weakly bound forms of cyanide

not measurable as free cyanide are probably also toxic.

A few analytical methods

measure forms of cyanide that are not all

inclusive as is total cyanide.

One of these, weak

acid dissociable cyanide, was chosen as the best available alternative.

A primary reason

for revising the cyanide standard

is because the original R88-21 two number cyanide

12

standard was derived using cold-water species.

New data from native warm water species

is considered

in this update because no search for new data has been conducted, to our

knowledge, since the early

1980s.

We are retaining weak acid dissociable cyanide as the

best available form to regulate.

This concludes my pre-filed testimony.

I will be supplementing this testimony as needed

during

the

hearing.

I would be happy to address

any questions.

January 29, 2002

By:

62el~4/C~

,S~

o~c2~~~i

Clark Olson

‘2

Illinois

Environmental

Protection Agency

1021

North Grand Avenue

East

P.O.

Box 19276

Springfield,

Illinois 62794-9276

THIS FILING PRINTED ON RECYCLED PAPER

13

RECEIVED

CLERK’S

OFFICE

BEFORE THE

ILLINOIS POLLUTION CONTROL BOARD

JAN

22

2002

STATE OF ILLINOIS

Pollution Control Board

IN

THE

MATTER OF:

WATER QUALITY AMENDMENTS

TO

)

35

III. Adm.

Code 302.208(e)-(g), 302.504(a),

)

R02-1 I

302.575(d), 303.444,

309.141(h); and

)

(Rulemaking

-

Water)

PROPOSED 35

III. Adm. Code 301 .267,

)

301.313, 301.413, 304.120, and 309.157

)

TESTIMONY OF ALAN KELLER

QUALIFICATIONS/INTRODUCTION

My name is Alan

Keller and

I

am the Supervisor of the Northern Municipal

Unit of

the

Permit Section of the

Division of Water Pollution Control.

I have worked for the

Agency since June

1972.

I have worked in

the Permit Section

my entire career with the

Agency and have been

responsible at one time or another with

all of the permit programs.

In my present capacity,

I

manage a

unit, which reviews construction

permits and NPDES

permits for municipal and semi-public facilities

and also perform other duties associated

with

municipalities.

I also serve on two design criteria groups, which establish

the specific

design criteria for sewers,

lift stations and treatment plants for municipal facilities.

One

group

is the Agency Division of Water Pollution Control Design Criteria Committee and the

other group is the Wastewater Design Criteria Committee for the Great Lakes-Upper

Mississippi River Board of State and

Provincial Public Health and Environmental

Managers.

I

have a Bachelor of Science

Degree

in Civil Engineering from the

University of

Illinois concentrating

in

Environmental

Engineering and

I am a Registered

Professional

Engineer in

Illinois.

My testimony will discuss the reasoning

behind

development of the

CBOD5 test.

14

REASONING BEHIND

CBOD5TEST

The Agency has interpreted the intent of 35

III. Adm. Code

304.120, with

respect to

compliance with the respective 5-day biochemical oxygen’~demand(BOD5) effluent

requirements, to be the 5-day carbonaceous biochemical oxygen demand (CBOD5).

35

III.

Adm. Code 309.141

allows the Agency to establish the terms and conditions of each

NPDES permit and directs the Agency to ensure compliance with the effluent limitations

under Sections 301

and 302 of the Clean Water Act.

40 CFR 133 provides for the

use of

CBOD5 for determining compliance with the definition of secondary treatment requirement.

This regulation was

revised in the September 20,

1984 Federal Register to allow for the

use of CBOD5.

The Agency has implemented the

use of CBOD5

in

lieu of BOD5

in

NPDES

permits since 1986 and also incorporates ammonia nitrogen water quality based

effluent limits where appropriate.

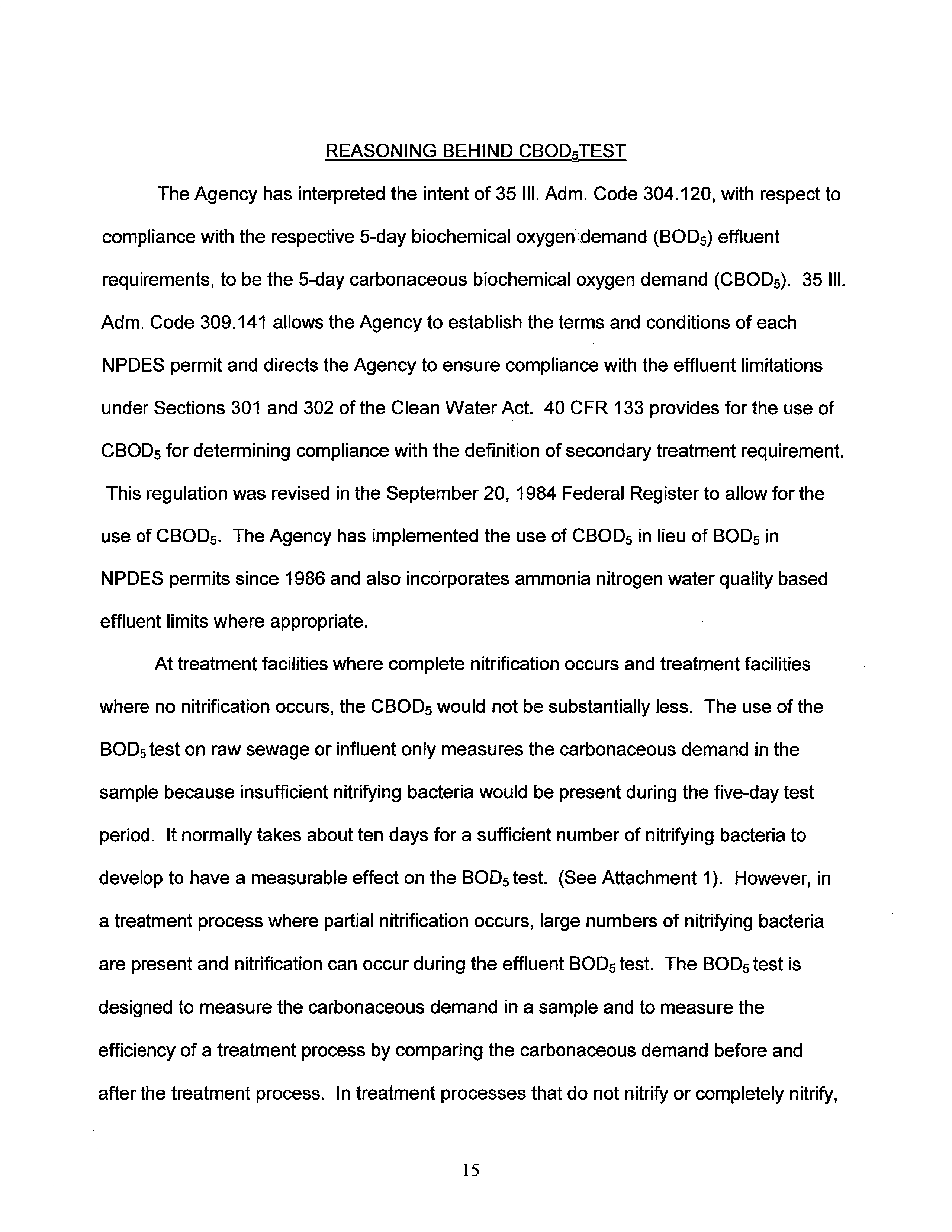

At treatment facilities where complete nitrification occurs and treatment facilities

where

no nitrification

occurs, the

CBOD5 would not be substantially less.

The use of the

BOD5test on raw sewage or influent only measures the carbonaceous demand in the

sample because insufficient nitrifying bacteria would be present during the five-day test

period.

It normally takes about ten days for

a sufficient number of nitrifying bacteria to

develop to have a measurable effect on the

BOD5 test.

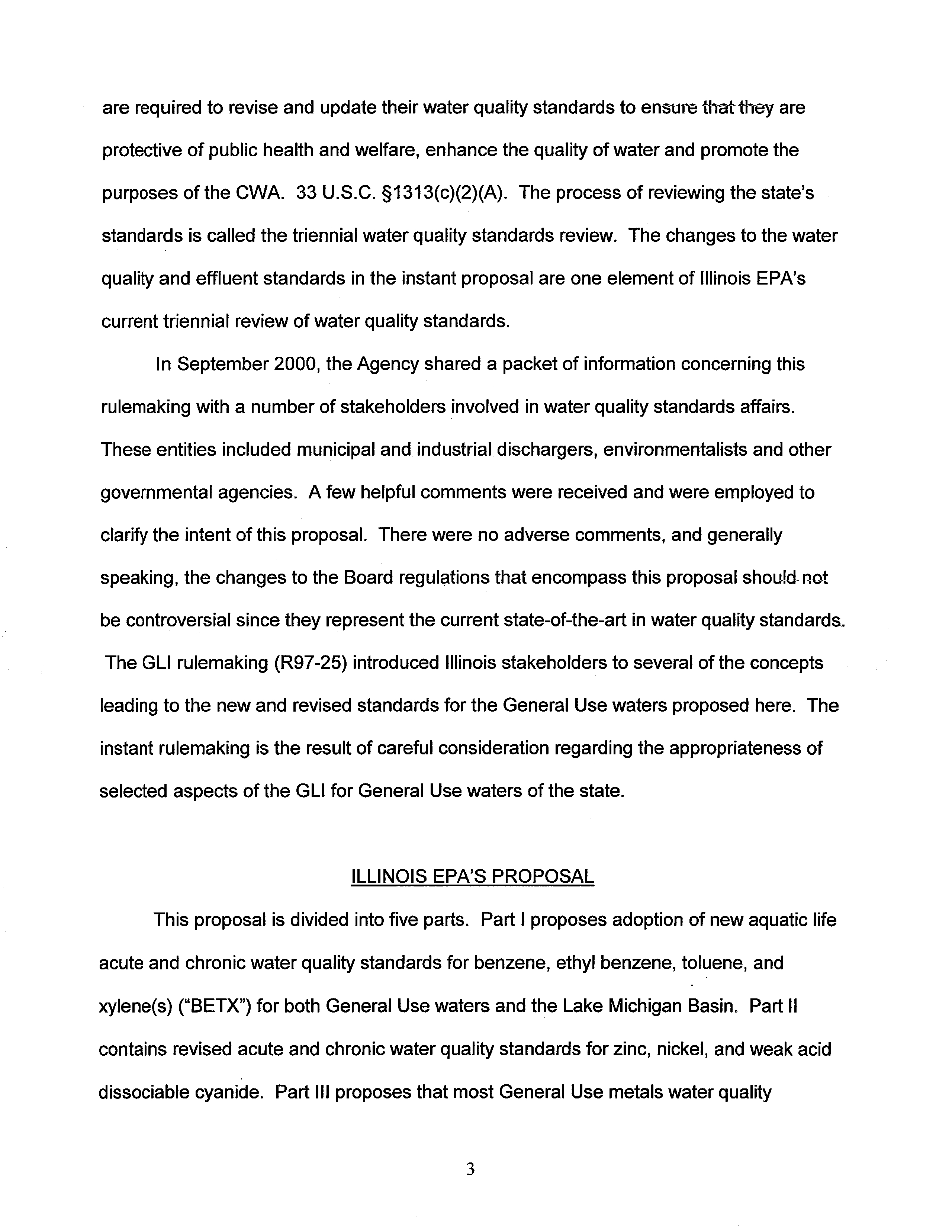

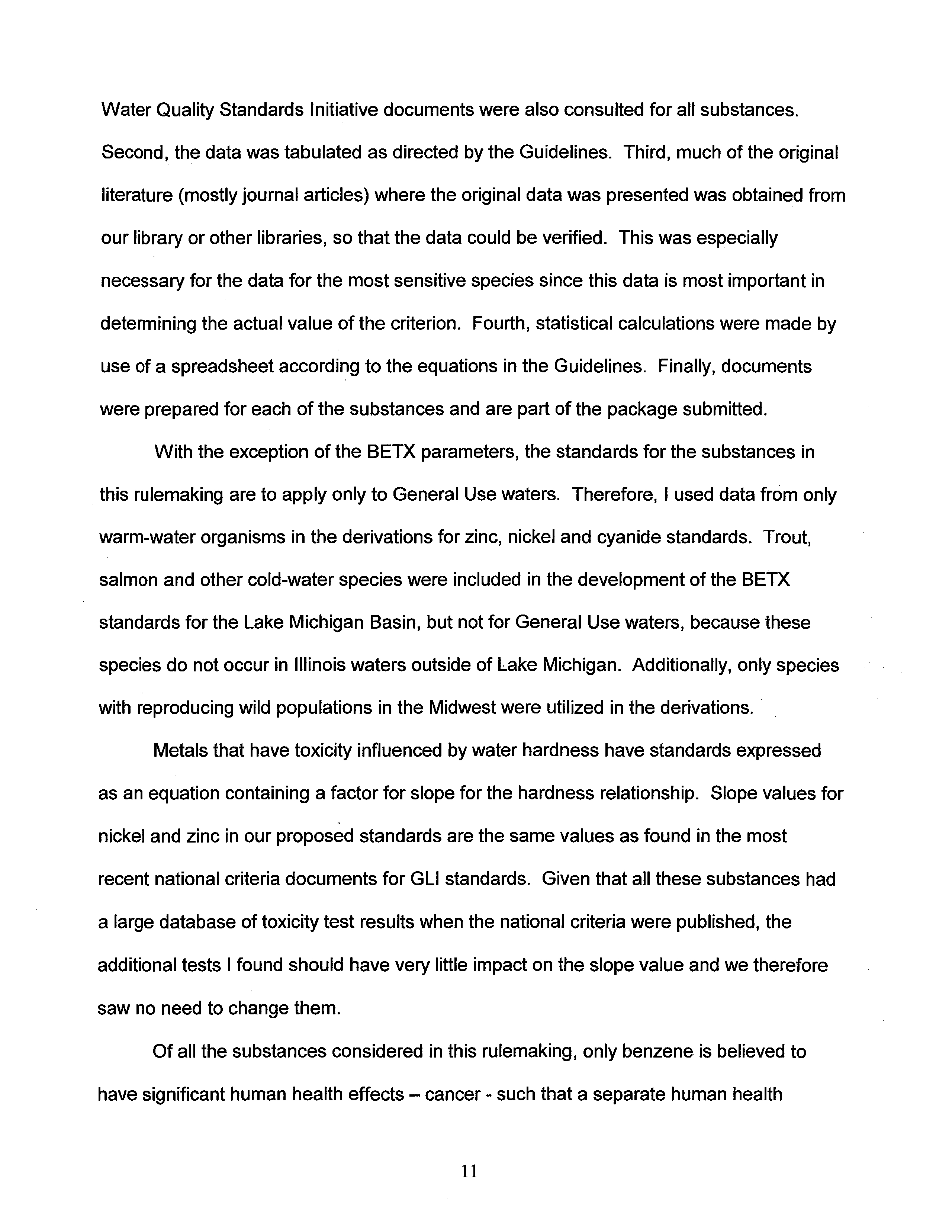

(See Attachment 1).

However, in

a treatment process where partial nitrification occurs,

large numbers of nitrifying bacteria

are present and nitrification can occur during the effluent BOD5test.

The

BOD5 test is

designed to measure the carbonaceous demand in

a sample and to measure the

efficiency of a treatment process by comparing the carbonaceous demand before and

after the treatment process.

In treatment processes that do not nitrify

or completely nitrify,

15

the

use of the

BOD5 test on both the influent and effluent will

provide satisfactory results.

However, in treatment processes that partially nitrify, the

use of the

BOD5test on both the

influent and effluent will compare the carbonaceous demand

in the influent with the

carbonaceous and nitrogenous demand

in

the effluent.

Such

a procedure would provide

no useful information on the carbonaceous removal efficiency in a treatment process.

An

accurate determination of the

removal efficiency of a treatment process

in which partial

nitrification occurs would require the carbonaceous demand of the influent to be measured

by the

BOD5 test and the carbonaceous demand of the effluent to be measured by the

CBOD5 test, which suppresses the nitrogenous demand.

Requiring the

BOD5test on the

influent and the

CBOD5 test on the effluent of all facilities would allow a uniform policy on

carbonaceous removal throughout the state.

The effluent from

a treatment plant consists

of many components, the Agency believes that the quality of the effluent can best be

assessed, and controlled, when each of the components are analyzed

and controlled

individually.

The characteristics of the effluent can

best be assessed when

the CBOD5

test is

used to measure the carbonaceous demand, and where ammonia nitrogen effluent

standards are appropriate,

use the ammonia nitrogen test to measure the nitrogenous

demand.

This procedure would be more logical than trying to measure the combined

carbonaceous and nitrogenous demand with the BOD5 test, which has been proven to

provide inconsistent and misleading

results.

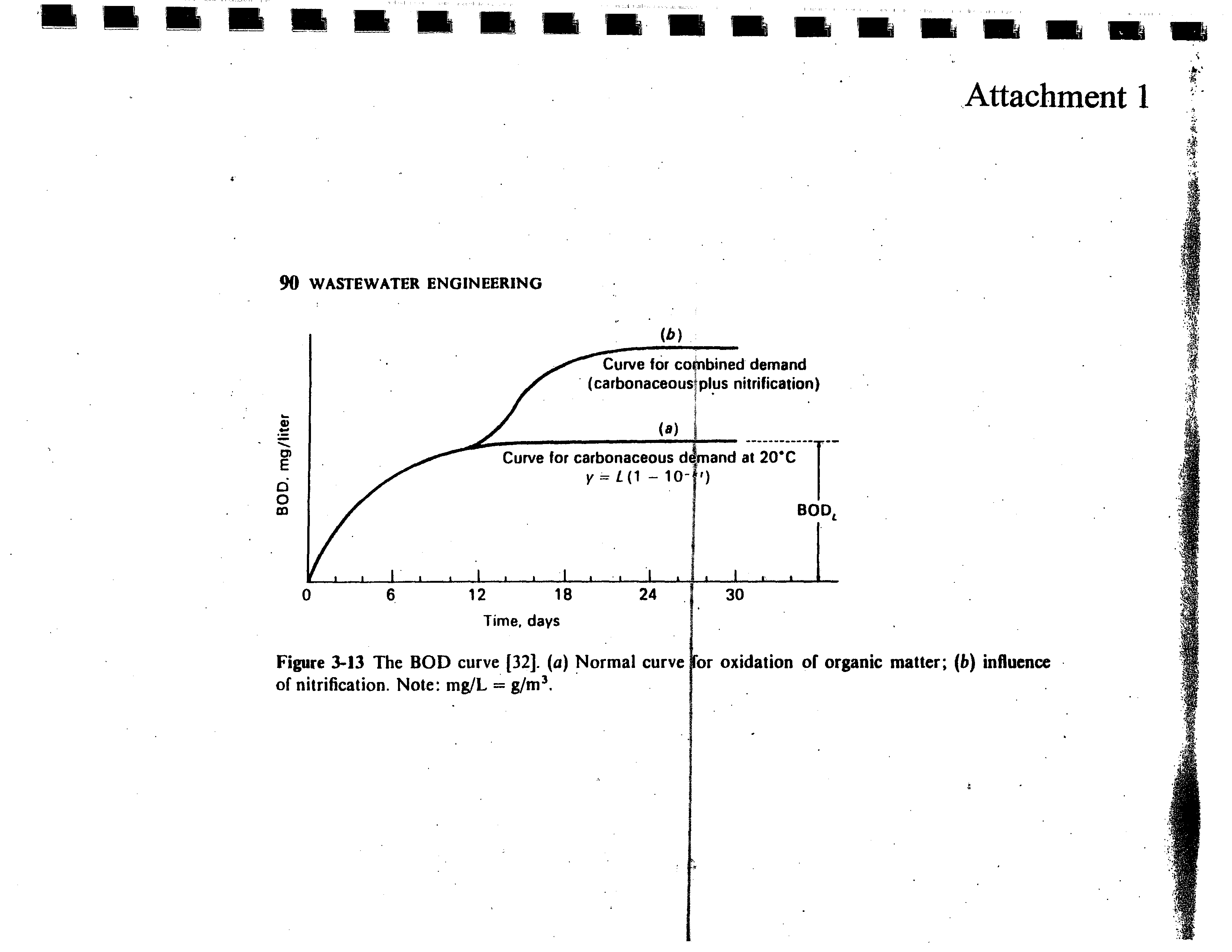

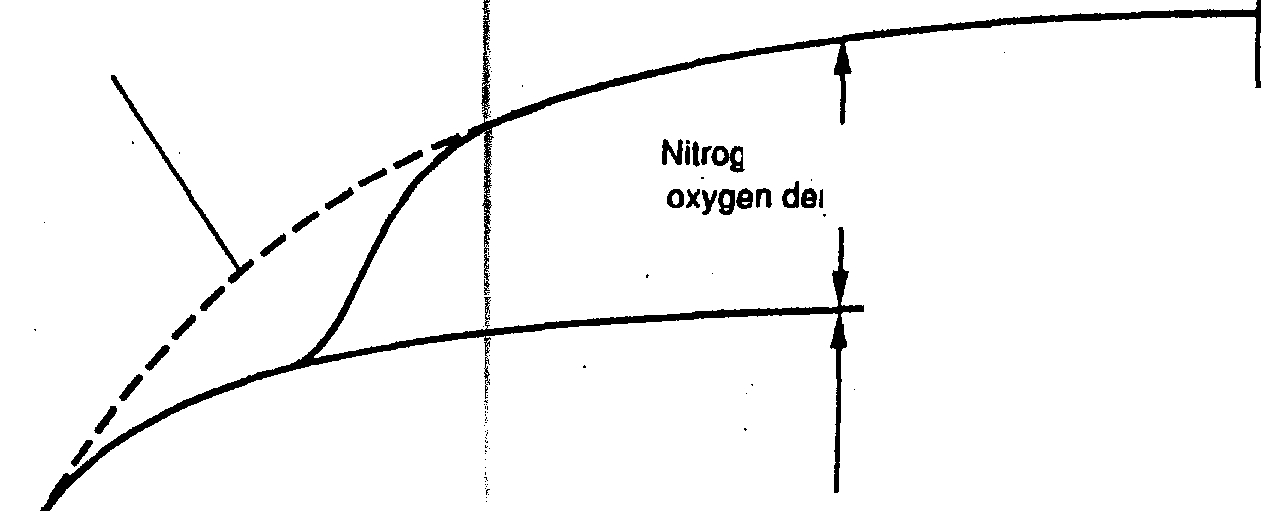

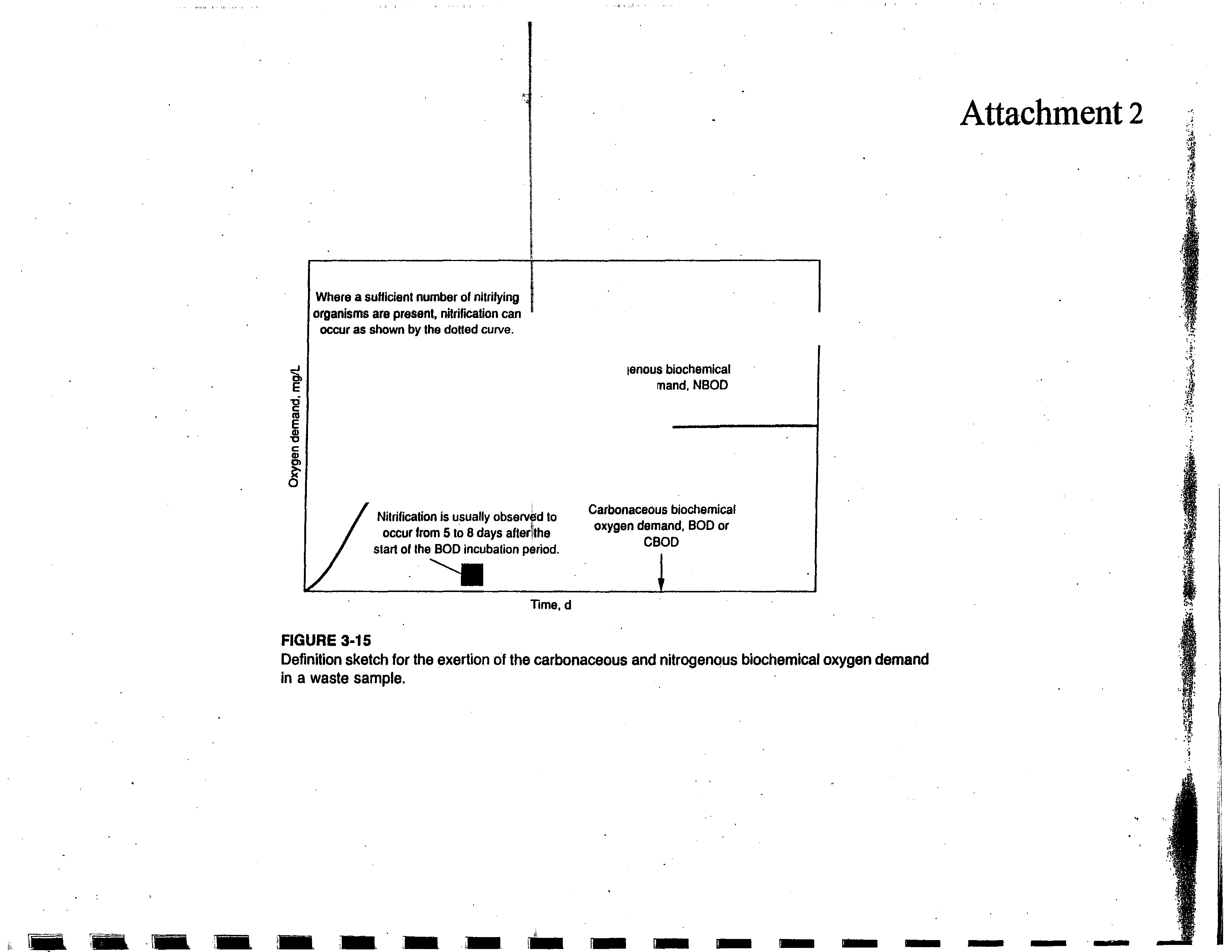

In addition, the attached figures depict the

influence of nitrification on the

BOD test.

Attachment

1 was taken from Metcalf and Eddy’s, “Wastewater Engineering: Treatment

Disposal,

Reuse” Second Edition,

page 90.

Attachment 2 was taken from Metcalf and

Eddy’s, Third Edition,

Page 76.

The Third

Edition also states the following: “Because the

reproductive rate of the

nitrifying bacteria

is slow it normally takes from 6 to 10 days for

16

them to reach significant numbers and to exert a measurable oxygen demand.

However,

if a sufficient number of nitrifying bacteria

are present initially, the interference caused by

nitrification can be significant.

When nitrification occurs in the BOD test, erroneous

interpretations of treatment operating data are possible.”

The Agency regulates the

nitrogenous biochemical oxygen demand of wastewater by incorporating the ammonia

nitrogen water quality based effluent limits

in NPDES Permits as appropriate under

Sections 304.105 and 304.122 of Subtitle C: Water Pollution.

This concludes my pre-filed testimony.

I will be supplementing this testimony as needed

during the hearing.

I would be happy to address any questions.

By:

(Le4L/

~

Alan

Keller

January 29, 2002

Illinois Environmental Protection Agency

1021 North Grand Avenue

East

P.O.

Box 19276

Springfield,

Illinois 62794-9276

THIS FILING PRINTED ON RECYCLED PAPER

17

lU

~

90

WASTEWATER

ENGINEERING

(b)

Attachment

1

Curve

for co

bined

demand

~~b~ac:ous~Plus

nitrification)

Figure

3-13

The

BOD

curve

132.

(a)

Normal

curve

of nitrification.

Note: mg/L

=

g/m3.

or

oxidation

of organic

matter;

(b)

influence

-S

a)

E

ci

0

Curve

for carbonaceousde

rnand at 20C

I)

BODL

I

.

0

6

12

18

24

Time. days

30

-J

E

0

C

E

Where a sufficient number of nitrilying

organisms are present. nitritication can

occur as shown by the dotted curve.

/

Nitrification

is usually observed to

occur from 5

to 8 days afterlihe

start ol

the ROD incubation period.

Time,

d

Attachment 2

FIGURE 3-15

Definition sketch for the exertion of the carbonaceous and nitrogenous biochemical oxygen demand

in a waste sample.

~

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

enous biochemical

nand, NBOD

Carbonaceous biochemical

oxygen demand,

BOO or

CBOD

1~

)

)

)

)

)

I,

the

undersigned,

on oath state that I have served the attached

WRITTEN

TESTIMONY OF ROBERT MOSHER, CLARK OLSON, AND ALAN KELLER

upon the

person to whom it is directed, by placing a copy in an envelop addressed to:

Dorothy Gunn, Clerk

Pollution Control Board

100 West Randolph

Street

Suite 11-500

Chicago,

Illinois 60601

(Federal Express)

Mathew Dunn

Illinois Attorney General’s Office

Environmental Control Division

James

R.

Thompson Center

100 West Randolph Street

Chicago,

Illinois 60601

(Federal Express)

Marie E. Tipsord

Illinois Pollution

Control Board

James

R.

Thompson Center

100 West Randolph Street,

Suite 11-500

Chicago,

Illinois 60601

(Federal Express)

Legal Service

Illinois Department of Natural

Resources

524 South Second Street

Springfield,

Illinois 62701-1787

(Federal Express)

and mailing

it from Springfield,

Illinois on January 18,

2002, with sufficient postage

affixed

as indicated above.

-~

-.

OFFICIAL

SEAL

BRENDA BOEHNER

X

NOTARY

PUBUC,

STATE

OF

ILLINOIS

$

tMY

COMMISSION

EXPIRES

11.14.2005*

STATE OF ILLINOIS

COUNTY OF

SANGAMON

SS

PROOF OF SERVICE

SUBSCRIBED AND SWORN TO BEFORE ME

this day of January 18, 2002.

Notary Public

THIS FILING PRINTED ON RECYCLED PAPER

18

Albert Ettinger

Environmental Law & PolicyCenter

35 E. Wacker Drive, Suite 1300

Chicago, Illinois

60601-2110

James T.

Hastington

Ross & Hardies

150

North Michigan, Suite

2500

Chicago,

Illinois

60601

Katherine

Hodge

Hodge & Dwyer

3150 Roland Ave., P0 Box

5776

Springfield, illinois

62705-5776

MargaretHoward

Hedinger and

Howard

1225

South Sixth Street

Springfield, illinois

62703

Robert Mesaina

illinois Enviommental Regulatory Group

215 East Adams Street

Springfield,, illinois

62701

Irwin Polls

600lWest Pershing Road

Cicero, illinois

60804-4112