| | - 217-782-7630 TDD: 312-814-6032

- FAX: 217-524-8508

- Water

- Simple Cycle

- Air Natural Gas

- HotExhaust

- LowEnergy

- Steam

- Water

- ColdWater

- HotWater

- EvaporatingWater

- Exhaust Wastewater

- 26, 27

- 34 3332

- 49, 5048

- WI5 WY

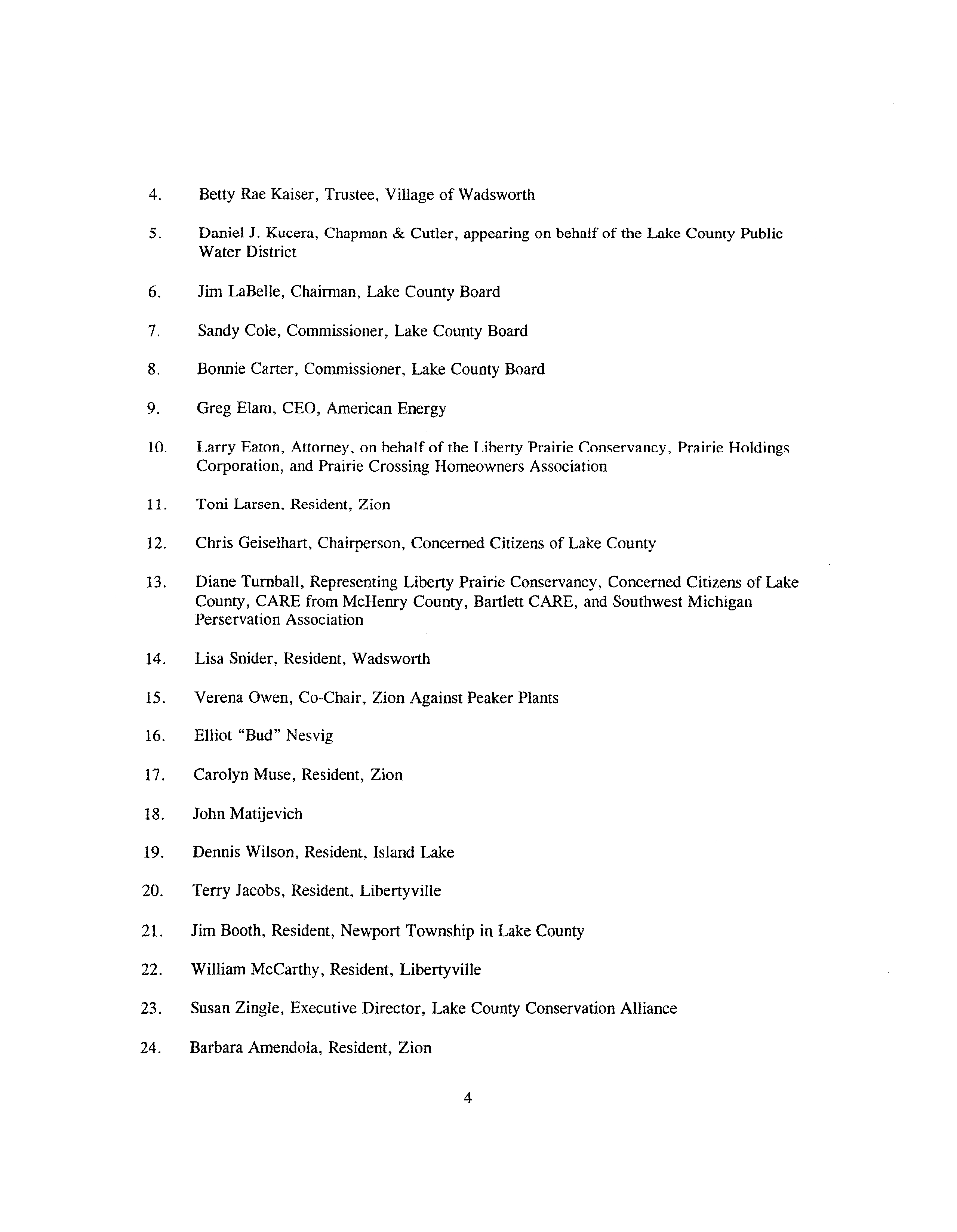

- Chicago Hearings

- Suburban Hearings

- Gravslake

- context of Peaker Plant Hearings

- CHICAGO HEARINGS

- Naumann

- Freddi Greenberg

- Prefiled Testimony

- NAPERVILLE HEARING

- Connie Schmidt, Representative of River Prairie Group

- Rural and City Preservation Association (.R&CPA~.Cathy Johnson, Vice Chair

- JOLIET HEARING

- Corn Products Internal. Inc., Alan Jirik. Director. Environmental Affairs

- Testimony of State Senator Terry Link

- Testimony of State Representative Susan Garrett

- Testimony of Sally Ball on behalf of State Representative Lauren Beth Gash

- Chapman & Cutler and Exchange with Board Member Kezelis

- Lake County Board. Bonnie Carter, Commissioner

- Zion

- Zion A2ainst Peaker Plants, Verena Owen. Co-Chair

- SPRINGFIELD HEARINGS

- Board Member McFawn

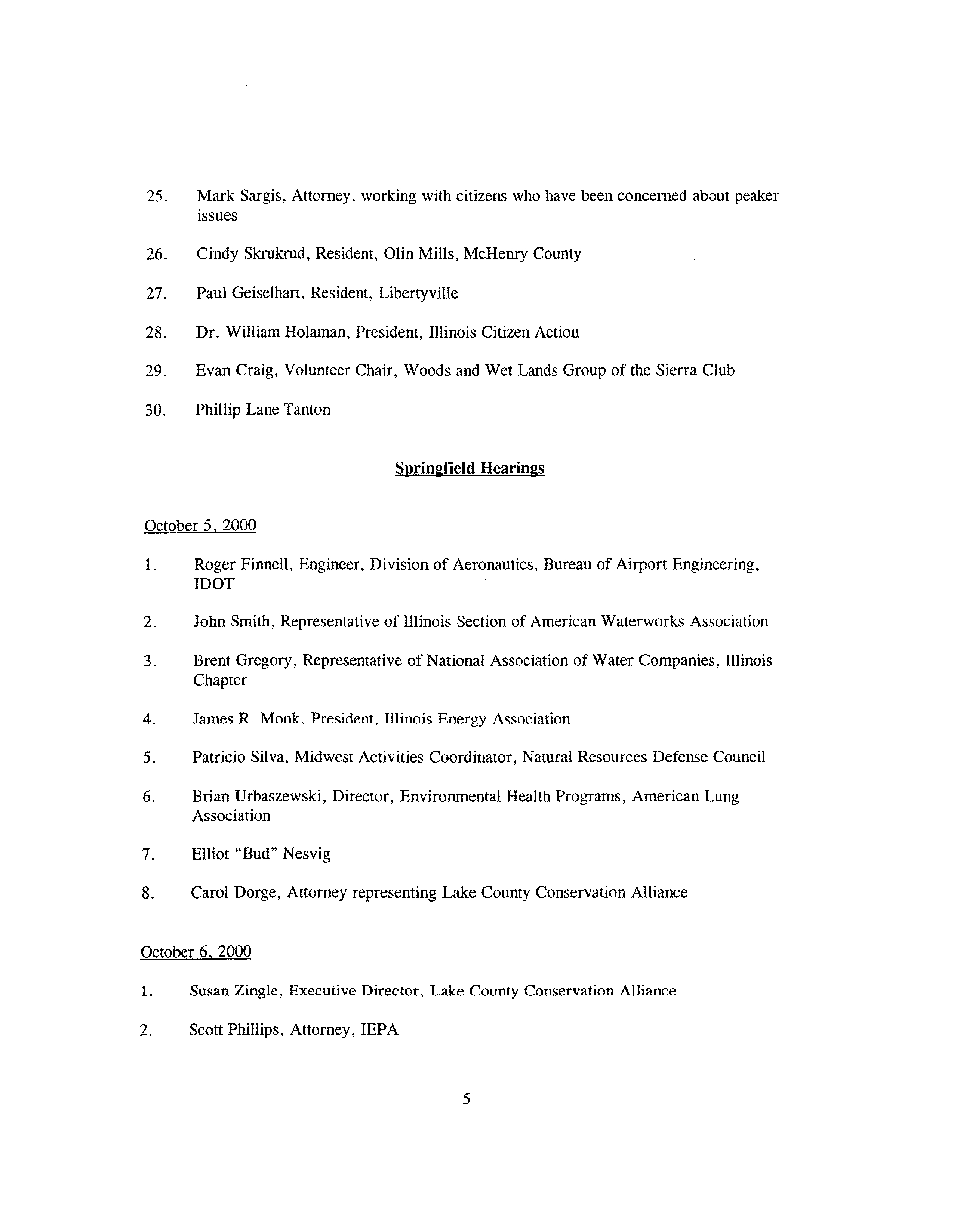

- ARIZONA

- EnergyPortfolio

- Electric Utility RestructuringEfforts

- CALIFORNIA

- Siting

- State Laws & RegulationsPeaker Plants

- Water

- Water Recycling Act of 1991

- CONNECTICUT

- EnergyPortfolio

- Noise

- State Policy RegardingNoise

- Siting

- Electrical Power Plant SitingAct, 1973

- GEORGIA

- Water

- Water Withdrawal Permits

- AirAir Permit Modeling

- HAWAII

- Noise

- ILLINOIS

- AirAir Pollution

- Energy Portfolio

- Renewable Energy Initiatives

- Noise

- INDIANA

- Siting

- Water

- EnergyPortfolio

- Electric Utility RestructuringLegislation

- Water

- Water Allocation and Use;Flood Plain Control

- Noise

- MAINE

- EnergyPortfolio

- Electric Utility RestructuringLegislation

- MASSACHUSETTS

- EnergyPortfolio

- Electric Utility RestructuringLegislation

- MICHIGAN

- AirEmissions Limitations and

- Prohibitions – New Sourcesof VOC Emissions

- MINNESOTA

- Siting

- Water

- Noise

- MISSOURI

- Water

- Geology, Water Resourcesand Geodetic Survey

- NEVADA

- EnergyPortfolio

- Electric Utility Restructuring,AB 366

- NEW JERSEY

- Water

- Water Supply ManagementAct

- Noise

- EnergyPortfolio

- Electric Utility Restructuring

- NEW YORK

- Siting

- Intervenor Fund for SitingReview

- Water

- Long Island WaterWithdrawal Restrictions

- Siting

- AirNOx – Reasonably Available

- Water

- Application for Permit formajor increase in withdrawalof waters of the State

- Registration of facilitiescapable of withdrawing>100,00 gal/day;

- Determination of reasonableuse of water

- EnergyPortfolio

-

- OREGON

- Noise

- Noise Control Classificationof Violations

- PENNSYLVANIA

- AirStationary Sources of NOx &

- Energy Portfolio

- TEXAS

- Water

- Siting

- EnergyPortfolio

- WISCONSIN

- Siting

- Water

- Water Quality and Quantity;General Regulations

|

IN THE MATTER OF: NATURAL GAS-FIRED,

PEAK-LOAD ELECTRICAL POWER GENERATING

FACILITIES (PEAKER PLANTS)

Docket No. R01-10

COMPANION REPORT TO THE ILLINOIS POLLUTION

CONTROL BOARD’S INFORMATIONAL ORDER OF

DECEMBER 21, 2000

TABLE OF CONTENTS

I. Introduction.............................................................................................. 1

II. Background on Peaker Plants ........................................................................ 2

A. Defining “Peaker Plant” ..................................................................... 2

B. Simple Cycle and Combined Cycle Turbines............................................. 5

C.

Fuels Used...................................................................................... 6

D. Number and Location of Existing and Proposed Peaker Plants ....................... 7

III. Air Emissions ........................................................................................... 8

A. Concerns of Citizens—Generally ........................................................... 8

B. Type and Amount of Air Emissions........................................................ 9

C. Air Pollution Control Regulations.........................................................14

D. Air Emissions Control Technology .......................................................25

E. Air Quality Modeling........................................................................27

F. Air Quality Impacts ..........................................................................31

G. Other Specific Concerns of Citizens ......................................................33

IV. Noise Emissions .......................................................................................33

A. Concerns of Citizens.........................................................................33

B. Peaker Plant Noise Emissions..............................................................36

C. Noise Control Methods......................................................................41

D. Noise Pollution Regulation .................................................................44

V. Water Quality ..........................................................................................53

A. Wastewater ....................................................................................53

B. Wastewater Regulation ......................................................................54

C. Stormwater Runoff ...........................................................................56

D. Wetlands .......................................................................................57

VI. Solid Waste .............................................................................................57

VII. Water Quantity.........................................................................................58

A. Information from State Government ......................................................58

B. Information from Local Government .....................................................61

C. Information from Industry ..................................................................66

D. Concerns of State Legislators and Citizens ..............................................66

VIII. Restructuring and Its Impacts .......................................................................68

A. Introduction....................................................................................68

B. History of Deregulation .....................................................................70

C. Environmental Effects of Deregulation...................................................78

D. Impact of Deregulation on Local Zoning.................................................78

E. Current and Future Retail and Wholesale Energy Markets ...........................82

F. Supply and Demand for Electric Power ..................................................85

G. The Need for Peaker Plants in Illinois....................................................91

H. Importing and Exporting Power Generated by Peaker Plants ........................93

I. Illinois Lacks a Statewide Energy Plan...................................................96

J. Effects of Peaker Plants on Electric Transmission and Distribution Systems......98

IX. Siting .............................................................................................. 103

A. Concerns of Citizens ........................................................................ 104

B. Suggestions of Citizens ..................................................................... 108

C. Information from State Government ..................................................... 114

D. Information from Industry ................................................................. 118

E. Information from Local Government .................................................... 122

X. Moratorium........................................................................................... 127

A. Information from Citizens ................................................................ 127

B. Information from State Government .................................................... 128

C. Information from Local Government ................................................... 129

XI. Health and Safety.................................................................................... 130

A. Health and Safety Concerns Generally ................................................. 130

B. Aviation Concerns.......................................................................... 134

C. Vibration Concerns ........................................................................ 136

D. Decommissioning Concerns .............................................................. 137

APPENDICES

Appendix A Summary of the Informational Order

Appendix B Persons Testifying

Appendix C Exhibit List

Appendix D Public Comments

Appendix E Abbreviation List

Appendix F

Figure 1 Typical Daily Load Curve

Figure 2 Simple Cycle and Combined Cycle Combustion Turbine Power Plant

Table 1 Existing & New Natural Gas-Fired, Simple Cycle and Combined

Cycle Units

Figure 3 Map of Existing & New Natural Gas-Fired, Simple Cycle and

Combined Cycle Units

Figure 4 National Combustion Turbine Projects

Appendix G Chairman Manning’s October 25, 2000 Submittal to the Water Resources

Advisory Committee

Appendix H New York and California Siting Processes

Appendix I Illinois SB 172 Siting Criteria

Appendix J State Laws & Regulations

Appendix K Additional Summaries of Public Comments

I. INTRODUCTION

On July 6, 2000, Governor George H. Ryan requested that the Illinois Pollution Control

Board (Board) conduct inquiry hearings on the potential environmental impact of natural gas-

fired, peak-load electrical power generating facilities, known as peaker plants. The Board

opened this docket, R01-10, on July 13, 2000, and has completed its inquiry hearings.

This Report is a companion to the Informational Order that the Board issued on December

21, 2000. The Report summarizes the record on which the Board based its Informational Order.

The record includes the testimony, hearing exhibits, and public comments that the Board received

during the inquiry hearing proceedings.

The Board’s findings and recommendations are not set forth in this Report, but rather in

the Informational Order. In the Informational Order, the Board made several recommendations

to tighten environmental regulations with respect to peaker plants. A summary of the

Informational Order is attached to this Report as Appendix A. The Informational Order and the

Report are available on the Board’s Web site (www.ipcb.state.il.us) and from the Board’s offices

in Chicago (312-814-3620) and Springfield (217-524-8500).

This Report organizes the record information into ten broad subject matters: (1)

background on peaker plants; (2) air emissions; (3) noise emissions; (4) water quality; (5) solid

waste; (6) water quantity; (7) electric industry restructuring and its impacts; (8) siting; (9)

moratorium; and (10) health and safety. The Report also includes a number of appendices, as

described in the preceding table of contents.

Board Hearing Officer Amy Jackson conducted seven days of public hearings at five

locations: August 23 and 24, 2000, in Chicago; September 7, 2000, in Naperville; September

14, 2000, in Joliet; September 21, 2000, in Grayslake; and October 5 and 6, 2000, in

Springfield. All seven Board Members attended each day of hearing. Over 80 persons testified,

including individual citizens, representatives of citizen groups, representatives of State and local

government, and representatives of industry. Please refer to Appendix B for a list of all hearing

participants. The Board appreciates their assistance in developing this record.

A court reporter transcribed each hearing, resulting in nearly 1,300 pages of transcripts.

The hearing transcripts have been available on the Board’s Web site.

1 Hearing Officer Jackson

admitted 69 hearing exhibits into the record, a list of which is attached as Appendix C.

2 In

1 The transcript pages for the first four hearing locations are numbered consecutively,

i.e.

,

Chicago (pp. 1-364), Naperville (pp. 365-574), Joliet (pp. 575-735), and Grayslake (pp. 736-

1,036). These pages are cited as “Tr.1 at [page number].” The transcript for the fifth and

final hearing, in Springfield (pp. 1-263), is cited as “Tr.2 at [page number].”

2 Hearing Officer Jackson identified hearing exhibits by the name of the participant submitting

the exhibit, and by the number of exhibits submitted by the participant. Hearing exhibits are

cited as “[participant] Exh. [number] at [page number].” Hearing exhibits submitted as a

group of exhibits are cited as “[participant] Grp. Exh. [number] at [page number].”

2

addition, the Board received 195 written public comments, which also have been available on the

Board’s Web site. Please refer to Appendix D for a list of all public comments.

3 The Board

thanks the commentors for their insights.

II. BACKGROUND ON PEAKER PLANTS

In this part of the Report, the Board summarizes information from the record on (1)

defining “peaker plant,” (2) simple cycle and combined cycle turbines, (3) the types of fuels

used in turbines, and (4) the number and location of existing and proposed peaker plants.

A. Defining “Peaker Plant”

1. Information from State Government

Mr. Thomas Skinner, Director of the Illinois Environmental Protection Agency

(IEPA),

4 explained when peaker plants operate:

Peakers operate only during peak demand situations such as on hot summer days

when residential and commercial usage of electricity creates more demands than

the baseload plants that exist in Illinois make available. Tr.1 at 52.

In its “Peaker Power Plant Fact Sheet,” IEPA further explained that peak demand in Illinois

typically “occurs during the summer months when air conditioning load is high, and the

nuclear and coal burning power plants cannot meet the demand for power.” IEPA Grp. Exh.

2, No. 20.

2. Information from Industry

Mr. Gerald M. Erjavec, Manager of Business Development for Indeck Energy

Services, Inc. (Indeck), described peaker plants:

“Peaking” plants are so named because their practical use is limited to operating

during periods of the highest or “peak” need for electricity. As can well be

imagined, the use of electricity varies over the day. From periods of low use

over night to the time of high use during the day, generating units are turned on,

or dispatched, to meet the needs of the system . . . . During the highest demand

period of the day, particularly in hot weather when there is more need for

electricity to power air conditioners, the peaking units are dispatched on.

Indeck Exh. 1 at 1.

3 Each public comment is assigned a number, beginning with the number one and continuing

through 195. Public comments are cited as “PC [number] at [page number].”

4 A list of abbreviations used in the Report is set forth in Appendix E.

3

According to Mr. Richard A. Bulley, Executive Director of Mid-America Interconnected

Network, Inc. (MAIN), air conditioning can account for up to 40% of the load on hot summer

days in Illinois. Tr.1 at 321.

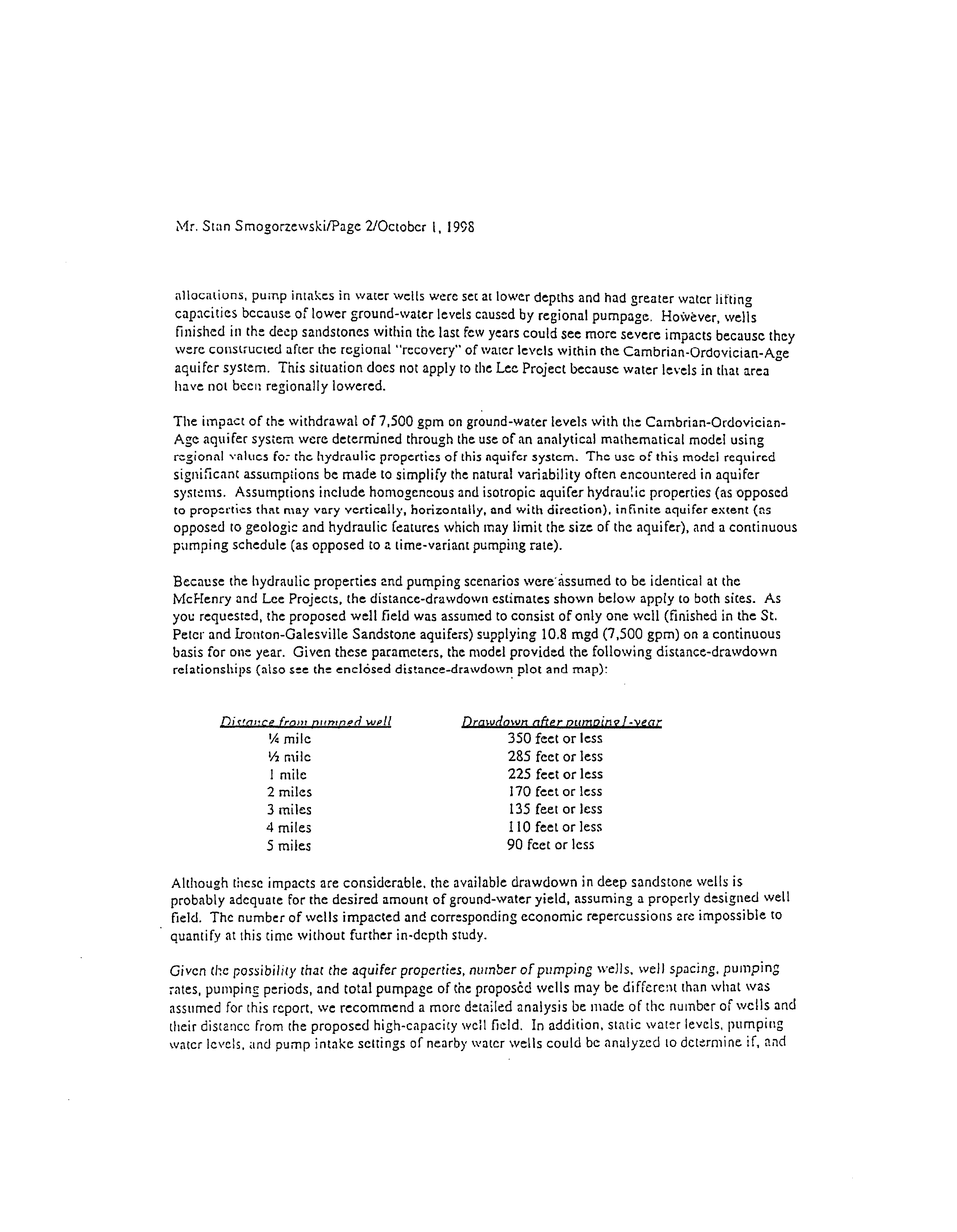

Reliant Energy Power Generation, Inc. (Reliant), graphed the typical daily load curve

to describe how electricity demand fluctuates. PC 1, Att. 1. The graph is set forth as Figure 1

in Appendix F of this Report. Reliant noted that there are three main categories of electricity

demand: base, intermediate, and peak. Base-load demand is the constant demand for

electricity that exists day and night, season to season. Reliant stated that base-load units “with

low operating costs, such as nuclear and coal-fired plants, are ideally suited to run at full

capacity at all times.” PC 1 at 2. Intermediate demand rises and falls as the day goes on, and

intermediate or load-following plants:

[A]re ramped up and down to follow the daily load curve of electricity demand.

* * * Together, [base-load and intermediate-load plants] cover most of the daily

and seasonal fluctuations in demand. This, however, leaves a few hours in the

year when unusually high demand peaks are encountered. * * * Peaking

units—or peakers—are used to meet these spike demands for power. PC 1 at 2.

Mr. Richard Ryan of Standard Power and Light narrowed the definition of peak

demand to a predictable calendar basis:

Peak really means 5 by 16. It’s five days a week, 16 hours a day. * * * You

have on-peak and off-peak. On-peak months would be May through September,

December, January and February. Off-peak would be all the out months. So

you have on-peak and off-peak months and then you have on-peak and off-peak

hours. Tr.1 at 427.

Commonwealth Edison Company (ComEd) noted that “electric power is not readily stored.”

ComEd Exh. 1 at 3. To respond efficiently and economically to peak needs for power, a

“peak load plant, or peaker, can be started relatively quickly” to meet the demand not readily

supplied by base or intermediate-load plants. ComEd Exh. 1 at 4. ComEd explained that

peaker plants “have high hourly operating costs, but low capital costs compared to base load

plants. Because of this cost structure, it is economical to supply peak load, in the relatively

few hours required, using this type of plant.” ComEd Exh. 1 at 4.

Besides meeting peak demand, peaker plants can address temporary shortages in power

supply. Mr. Christopher Romaine, Manager of the Utility Unit in IEPA’s Division of Air

Pollution Control, explained:

[I]f there is an unexpected outage of a power plant during the winter period of

time, there is an event to be able to turn on the peaker plant. So that would be a

4

time where we might call upon a peaker plant some other period of the year than

summer. * * * [P]eaker plants can also be used to meet an emergency demand

for power, when . . . there is a breakdown of a substation or power lines

(assuming power can still be carried to the area where it is needed). Tr.1 at

179; IEPA Grp. Exh. 1, Romaine at 3.

Comparing summer and winter peak loads, ComEd noted that the all-time summer peak

load was 21,243 megawatts (MW) on July 30, 1999, between 2:00 p.m. and 3:00 p.m. central

time. ComEd’s all-time peak load during a winter month was 14,484 MW on December 20,

1999, between 5:00 p.m. and 6:00 p.m. ComEd Exh. 1 at 3.

The Illinois Environmental Regulatory Group (IERG), an affiliate of the Illinois State

Chamber of Commerce, stated:

[T]he industrial community is adjusting to [electric industry] deregulation . . .

by exploring the increased use of on-site co-generation facilities. These

facilities are intended to provide both electricity and steam to the host facility.

IERG Exh. 1 at 3.

Mr. Alan Jirik, Director of Environmental Affairs for Corn Products International, Inc. (CPI)

testified that these co-generation units often use gas-fired turbines. Tr.1 at 631. He explained

that the industrial community seeks not only to use co-generation units to produce steam for its

operations, but also to sell any excess electricity on the grid. Tr.1 at 632.

However, IERG stressed that “a ‘peaker plant’ is very different from on-site units at an

industrial facility, in terms of physical and operational characteristics, as well as financial

investment and return.” IERG Exh. 1 at 4. IERG encouraged the Board to restrict its findings

to “ ‘peaker plants’ and not to other types of electric generating facilities, be they on-site

emergency generators, co-generation units or base-load power plants.” IERG Exh. 1 at 4.

Similarly, Mr. Jirik of CPI emphasized that these industrial co-generation units should

be distinguished from peaker plants:

Industrial cogeneration units are typically base loaded as industrial processes

demand a relatively constant supply of steam and electricity. This constant

demand essentially precludes peak-only operation. Tr.1 at 631. * * * These

units will provide steam and electricity to the manufacturing operation, and by

virtue of their capacity, also provide electricity to the grid. We expect to

maximize our sales to the grid during times of peak pricing, which usually

occurs during periods of peak demand. However, these industrial cogen units

differ from the peakers that are the subject of [these] hearing[s]. Tr.1 at 632.

5

3. Concerns of Citizens

Referring to the federal definition of a peaking unit,

5 Ms. Susan Zingle, Executive

Director of the Lake County Conservation Alliance (LCCA), testified that “peaker plants are

expected to operate about 10 percent of the time, approximately 876 hours.” Tr.2 at 169. She

noted that Director Skinner of IEPA, in a May 16, 2000 letter to the United States

Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) about regulating peaker plants, said that peaker

plants “were expected to run about 20 days a year [or] . . . 300 hours.” Tr.2 at 169. She

contrasted this with “plants [in Illinois] claiming to be peakers [and] being permitted for 2,300,

3,300, 4,000 hours, not 300 to 900 [hours].” Tr.2 at 170. Ms. Zingle concluded:

[T]otal demand on the ComEd system has been as high as about 21,000 [MW],

so peaking power within MAIN should be about 2,000 [MW], not the 22,000

[MW] we have being permitted now. In the applications, most of these plants

have some indication that they plan to operate year-round. I don't believe these

are peakers. These are intermediate load plants. Tr.2 at 170.

After observing the Chicago hearings in August, Ms. Dianne Turnball, a consultant to

several citizen groups, noted at the Naperville hearing that “[w]e keep talking about peaker

plants and we seem to eliminate the combined cycle plants.” Tr.1 at 434. She argued that the

Board should address combined cycle plants. She also suggested that any rule changes should

apply to independent power producers (IPPs), except those that operate base-load plants. Tr.1

at 435.

B. Simple Cycle and Combined Cycle Turbines

1. Information from State Government

Recently, most power plant air permit applications filed with IEPA have been for

natural gas-fired, simple cycle combustion turbines ranging in capacity from 25 to 187 MW

per turbine. PC 168, Att. 2. However, not all natural gas-fired peaker plants are simple

cycle. PC 9 at 31. IEPA noted:

All power plants are used to meet peak electricity demands. During periods of

peak electricity demand, base-load power plants and the cyclic [intermediate or

load-following] power plants are in service, which would also include combined

cycle plants. PC 9 at 31.

5 “Peaking Unit means: (1) A unit that has: (i) An average capacity factor of no more than

10.0 percent during the previous three calendar years and (ii) A capacity factor of no more

than 20.0 percent in each of those calendar years . . . .” 40 C.F.R. § 72.2.

6

Mr. Romaine of IEPA described a gas turbine and explained how it works. A “gas

turbine is a rotary internal combustion engine with three major parts . . . an air compressor,

burner(s) or combustion chamber, and a power turbine.” Tr.1 at 75. The air compressor

compresses incoming air, diverting a portion to the burners where the fuel is burned. “This

very hot gas is mixed with the rest of the compressed air and passes through the power

turbine.” Tr.1 at 75. The hot compressed gas expands to push the blades of the power

turbine. “The power turbine turns the generator and makes electricity.” Tr.1 at 76.

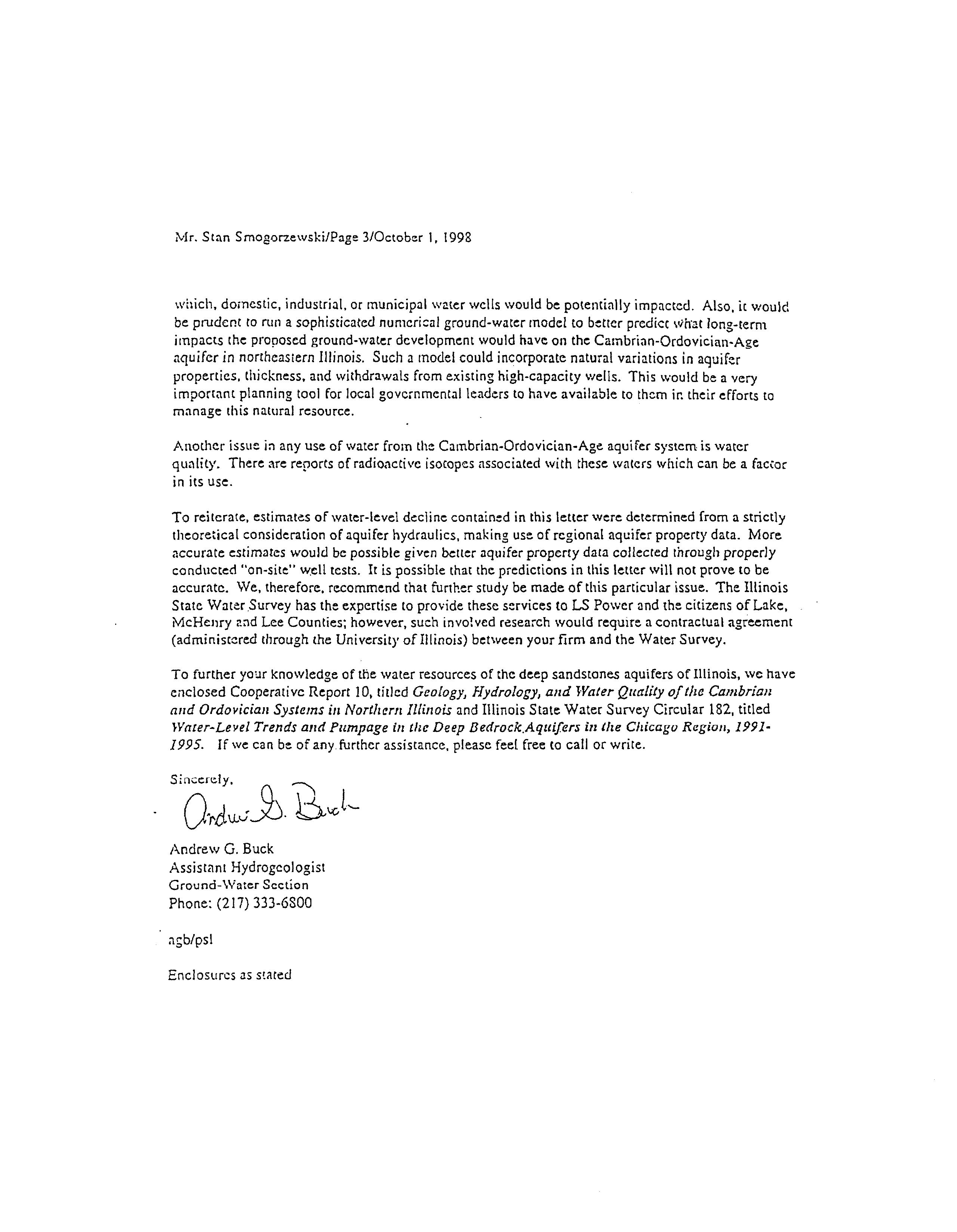

Mr. Romaine also discussed the differences between simple cycle and combined cycle

gas turbines. With simple cycle turbines, the “waste heat from the exhaust from the gas

turbine is directly discharged to the atmosphere with the exhaust gases.” Tr.1 at 76. With

combined cycle turbines:

[T]he hot exhaust gases discharged from the turbine . . . are ducted through a

waste heat boiler and used to generate steam. This steam is then used to drive a

steam turbine generator, as in more traditional steam power plants. * * * The

recovery of heat energy in the exhaust of a gas turbine in this combined cycle

fashion can increase the energy efficiency of a combined cycle plant by about 50

percent as compared to a simple cycle turbine . . . .” Tr.1 at 77-78.

The generation capacity of simple cycle plants ranges from 25 to 800 MW per plant.

The generation capacity of combined cycle plants ranges from 336 MW to 2,500 MW. PC

168, Att. 1.

2. Information from Industry

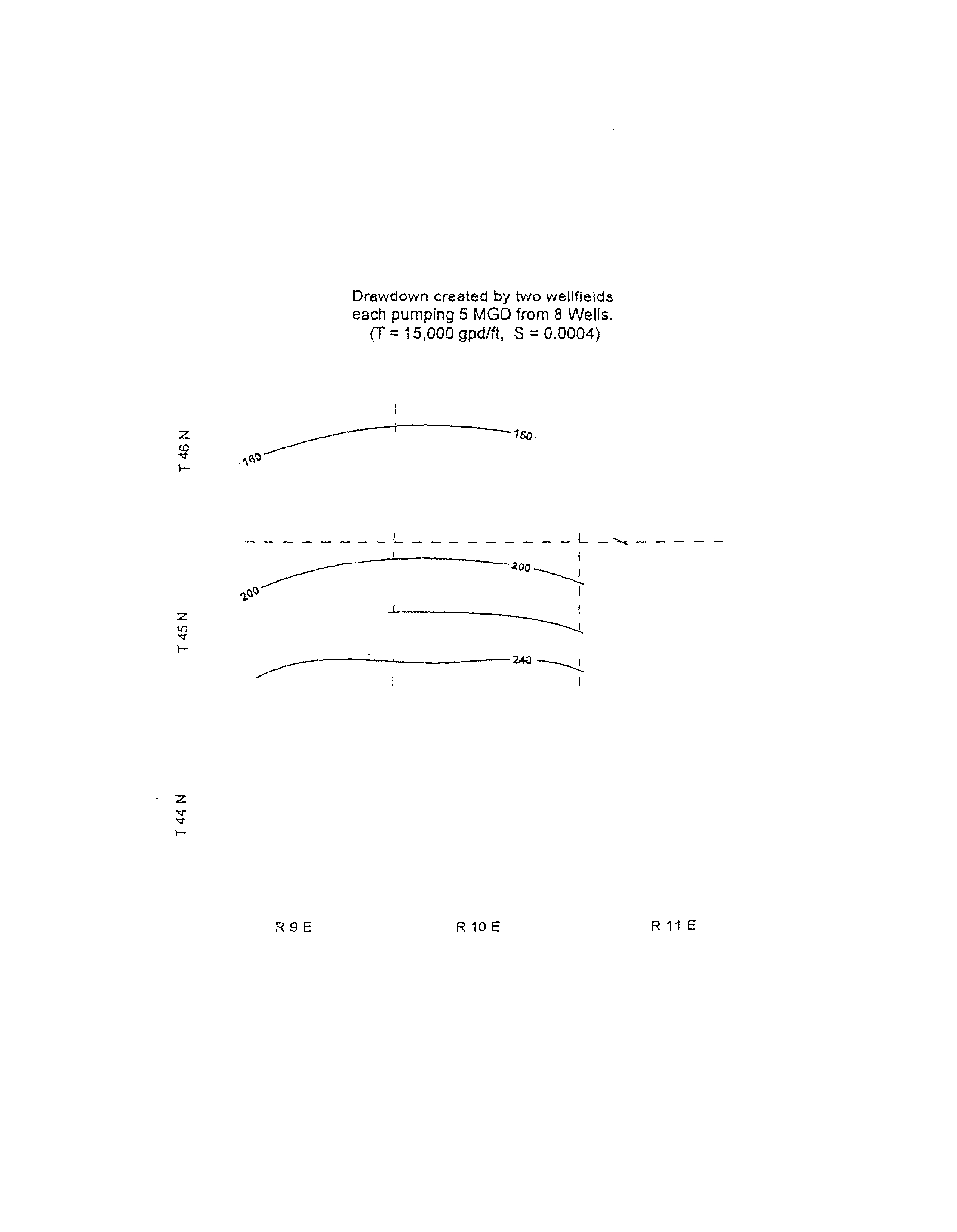

Mr. Erjavec of Indeck presented a diagram of simple cycle and combined cycle natural

gas-fired plants. This diagram is set forth as Figure 2 in Appendix F of this Report.

3. Information from Citizens

Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) stated that “[c]ombustion turbines,

particularly combined cycle applications are capable of obtaining 55-60% efficiencies . . . .

Single cycle natural gas-fired combustion turbines are considerably less efficient, operating

between 28-35% with combustion controls limiting [nitrogen oxides] NOx emissions to 15-25

ppm [parts per million].” PC 109 at 5.

C. Fuels Used

1. Information from State Government

“Gas turbines . . . rely on the availability of a supply of clean fuel such as natural gas,

kerosene, or light oil. Note that gas turbines are called ‘gas’ turbines because the working

7

fluid is a hot gas, not because they burn natural gas.” IEPA Grp. Exh. 1, Romaine at 5. Mr.

Romaine of IEPA noted that all air permit applications filed with IEPA have “proposed the use

of natural gas as their primary fuel, but some applications have also included provisions to

have fuel oil as a backup fuel.” Tr.1 at 178. He confirmed that some plants originally

intended for natural gas may ultimately use a different fuel should the market allow: “the

plants that are going in with fuel oil capacity are really looking at being able to supply the

winter peaking market.” Tr.1 at 178.

Other fuels typically used for peak applications in Illinois include diesel, ethane, jet

fuel, fuel oil, #2 oil, and distillate oil. IEPA Grp. Exh. 2, Att. 8, 9. According to Mr.

Romaine, the fuel type dictates the character of the air emissions. As for plants using oil, Mr.

Romaine noted that “emissions would certainly be higher.” Tr.1 at 179. “Certainly it is more

difficult to control [nitrogen oxides] NOx as compared to oil than it is burning natural gas. Oil

has more ash than natural gas. Oil has some fats [that create] sulfur dioxide [SO2].” Tr.1 at

180.

2. Information from Industry

Mr. Erjavek of Indeck noted that light oil or diesel can be used to fuel gas turbines, but

that this practice is not as common in the United States as in other countries. Tr.1 at 225.

3. Concerns of Citizens

Ms. Carol Dorge, an attorney and Director of LCCA, expressed concerns about air

pollution from diesel fuel: “We also note that some of these facilities are being permitted to

use diesel fuel. They say they are using diesel for back up, but back up is not defined in their

applications or their draft permits.” Tr.1 at 450.

D. Number and Location of Existing and Proposed Peaker Plants

1. Information from State Government

Director Skinner of IEPA noted the increasing number of peaker plant air permit

applications that IEPA has received over the past year and a half: “We seem to get more every

day.” Tr.1 at 51. As Director Skinner explained, the total number of peaker plants depends

on whether you are counting “facilities” or “units.” A facility may have multiple units or

turbines. As of the August 24, 2000 Chicago hearing, IEPA had received permit applications

for 46 facilities. Tr.1 at 48.

Mr. Romaine stated:

These plants are being proposed throughout the state, not only in rural areas

where new power plants were historically sited, but also in developed and

8

developing areas in the greater Chicago metropolitan area. In the Chicago area,

some plants are being sited for existing industrial locations, but many have

selected sites that are not in industrial areas and might be best characterized as

open, often close to residential areas. * * * Like the existing peaker plants,

some [peaker plants being proposed by historic utilities] are occuring at or

adjacent to existing coal-fired power plants. IEPA Grp. Exh. 1, Romaine at 3-

4.

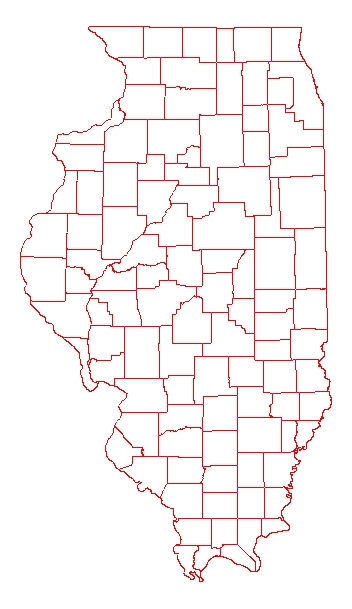

As of November 6, 2000, IEPA listed 67 air permits for existing and proposed power

plants using simple or combined cycle turbines. PC 168, Att. 2. A table and corresponding

map based on information from IEPA are set forth as Table 1 and Figure 3, respectively, in

Appendix F of this Report. Of the 67 air permits, 36 are for locations in ozone attainment

areas while 31 are in nonattainment areas (NAAs); 9 are for existing facilities while 58 are for

proposed facilties; 8 are for base load, 56 for peak load, and 3 for either base or peak load. If

all of the proposed facilities are built, total electrical capacity contributed by existing and

proposed gas-fired simple cycle and combined cycle plants will be 27,329 MW. IEPA Grp.

Exh. 2, No. 7; PC 168, Att. 2.

Mr. Charles Fisher, Executive Director of the Illinois Commerce Commission (ICC),

provided a USEPA document entitled National Combusion Turbine Projects, which lists

combustion turbine facilities across the United States that have draft permits or recently-issued

final permits. PC 8. A map based on this information is set forth as Figure 4 in Appendix F

of this Report.

2. Concerns of Citizens

As described throughout this Report, individual citizens and citizen groups consistently

expressed concerns over the growing number of proposed peaker plants, the proposed locations

of the plants (including clustering), and the resulting impacts to the environment.

6

III. AIR EMISSIONS

In this portion of the Report, the Board summarizes record information on (1) the

general concerns of citizens about air pollution, (2) the type and amount of air emissions from

peaker plants, (3) air pollution control regulations, (4) air emissions control technology, (5) air

quality modeling, (6) air quality impacts, and (7) other specific concerns of citizens about air

pollution.

6 For additional summaries of public comments, organized with a topical index, please refer to

Appendix K. Please refer to Appendix J for a comprehensive table on other states’ laws and

regulations that may affect peaker plants.

9

A. Concerns of Citizens—Generally

Potential air pollution from peaker plants was a major concern of individual citizens

and citizen groups testifying before the Board. In general, they were concerned about (1) the

impact on local air quality,

i.e.

, in the vicinity of peaker plants, (2) the impact on regional air

quality, including attaining the National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS), (3) the

adequacy of existing regulations and permit requirements to address the unique aspects of

peaker plant air emissions, and (4) the adequacy of emission control technology that peaker

plants use.

Citizens argued that peaker plants need to be regulated more strictly than current air

quality regulations provide. Tr.1 at 458, 919, 994-995; Tr.2 at 113 and 186. They asserted

that peaker plants pose a unique threat with respect to air pollution when compared to other

types of State-regulated facilities. Tr.1 461, 994-995 and Tr.2 at 188. Further, they argued

that if the Board determines that peaker plants should be more strictly regulated or restricted,

the new regulations or restrictions should apply both to existing and new facilities. Tr.2 at

189-190.

Specific concerns that individual citizens and citizen groups raised about particular air

emission subjects are summarized below when the record information on the particular subject

is summarized.

B. Type and Amount of Air Emissions

1. Information from Citizens

Many individual citizens and citizen groups expressed concern about the large amounts

of pollutants that peaker plants may emit during the summer months. Tr.1 at 646, 788, 923,

980. Ms. Carol Stark, Director of Citizens Against Ruining the Environment (CARE), stated

that emissions of nitrogen oxides (NOx) and volatile organic material (VOM) on hot summer

days contribute significantly to the formation of ground level ozone. Tr.1 at 646. She asserted

that it is not acceptable to have peaker plants in the NAA, which contains “some of the major

polluters in the State.” Tr.1 at 646.

Ms. Lucy Debarbaro of Citizens Against Power Plants in Residential Areas (CAPPRA)

expressed concern about the emission of greenhouse gases. She stated that carbon dioxide

(CO2) emissions from power plants significantly impact global climate change. Tr.1 at 497.

Ms. Debarbaro maintained that if CO2 emissions continue to increase, the greenhouse effect

may cause an irreversible large-scale impact on the environment. Tr.1 at 497.

2. Characteristics of Air Emissions

10

a. Information from Government. Mr. Romaine of IEPA testified about the

characteristics of air emissions from peaker plants. He has extensive experience in air

pollution control, including permitting peaker plants. IEPA Grp. Exh. 1, Romaine at 1-2.

The characteristics of peaker plant air emissions were also addressed by Versar, Inc. (Versar),

an environmental consultant. Versar was retained by the DuPage County Department of

Development and Environmental Concerns to review environmental issues related to peaker

plants. DuPage County Board Exh. 1 at 1.

Mr. Romaine stated that peaker plants emit air pollutants because they burn large

amounts of fossil fuel to generate electricity. He stated that these pollutants are combustion

byproducts and include NOx, carbon monoxide (CO), VOM, particulate matter (PM), and

sulfur dioxide (SO2). Tr.1 at 83-84; IEPA Grp. Exh. 1, Romaine at 10-11; see also DuPage

County Board Exh. 1 at 14. Mr. Romaine stated that NOx emissions are of particular interest

in part because gas turbines emit more NOx than the other pollutants. IEPA Grp. Exh. 1,

Romaine at 10. Versar stated that “NOx and CO are the pollutants emitted in the greatest

amount from a gas-fired turbine . . . .” However, CO generally causes less concern than NOx

“because NOx plays a role in ozone formation.” DuPage County Board Exh. 1 at 14.

Mr. Romaine relied on a USEPA publication entitled Alternative Control Techniques

Document—NOx Emissions from Stationary Gas Turbines to address NOx emissions from

peaker plants. IEPA Grp. Exh. 2, No. 2. Gas turbines form NOx in three ways. The primary

way involves forming “thermal NOx.” Thermal NOx is formed in the gas turbine combustor

from a series of chemical reactions. Nitrogen and oxygen in the combustion air dissociate and

subsequently react to form the different NOx. The second way involves forming “prompt

NOx.” Prompt NOx is formed from early reactions of nitrogen in combustion air and

hydrocarbon radicals in fuel. The third way involves forming “fuel NOx.” Fuel NOx is formed

from reactions between the fuel bound nitrogen compounds and oxygen. Because natural gas

has a negligible amount of fuel-bound nitrogen, “[e]ssentially all NOx formed from natural gas

combustion is thermal NOx.” IEPA Grp. Exh. 2, No. 2 at 3.1-3.

The reaction between nitrogen and oxygen leads to the formation of seven known

oxides of nitrogen. However, only nitric oxide (NO) and nitrogen dioxide (NO2) are formed in

sufficient quantities to be significant in air pollution. IEPA Grp. Exh. 2, No. 4 at 4-1. The

formation rate of thermal NOx increases exponentially with increase in temperature. In

addition, NOx formation in gas turbines is influenced by the combustor design, fuel type,

ambient conditions, operating cycles, and power output level. IEPA Grp. Exh. 1, Romaine at

10; IEPA Grp. Exh. 2, No. 4 at 4-6.

The combustor design is considered the most important factor affecting NOx formation

because flame temperature, fuel/air mixing, and residence time are controlled by the turbine

design. The type of fuel used to fire the turbine affects NOx emission levels. NOx emissions

are higher for fuels that burn at high flame temperatures. Ambient conditions, such as

humidity, temperature, and pressure, also affect NOx formation. Regarding operating cycles

11

(simple/combined), NOx emissions from identical turbines used in a simple cycle and a

combined cycle plant would have similar NOx emission levels, as long as a duct burner is not

used in the heat recovery applications of the combined cycle plant. A duct burner is a

supplemental burner used in combined cycle plants to increase the temperature of exhaust heat

from the gas turbine and thereby produce the desired quantity of steam. With a duct burner,

the NOx emissions level for the combined cycle plant would be higher than that for the simple

cycle plant. IEPA Grp. Exh. 2, No. 4 at 4-12.

Regarding other air pollutants, Mr. Romaine stated that CO is formed from incomplete

combustion when there is insufficient residence time at high temperatures or incomplete

mixing. IEPA Grp. Exh. 1, Romaine at 10. He also noted that gas turbines emit small

amounts of VOM. VOM also results from incomplete combustion. Mr. Romaine stated that

forming both CO and VOM depends on the loading of the gas turbine. A gas turbine operating

under full load will emit lower levels of CO and VOM because full load results in higher fuel

efficiency. Higher fuel efficiency in turn reduces the formation of CO and VOM. However,

higher fuel efficiency is more conducive to NOx formation. Thus, Mr. Romaine asserted that

when combustion modification is considered for reducing NOx emissions, compensatory steps

must be taken to maintain or even improve combustion efficiency. IEPA Grp. Exh. 1,

Romaine at 11.

Mr. Romaine stated that PM results mainly from the noncombustible trace constituents

present in the fuel. He noted that natural gas-fired turbines emit negligible amounts of PM.

Mr. Romaine stated that even turbines burning distillate oil emit very low amounts of PM due

to the low ash content of the fuel oil. IEPA Grp. Exh. 1, Romaine at 11. Versar stated that

natural gas is inherently clean burning fuel, and gas-fired turbines generally achieve a level of

combustion efficiency so as to be considered small sources of VOM and PM. DuPage County

Board Exh. 1 at 14. Mr. Romaine stated that peaker plants emit very low levels of SO2. SO2

results from burning sulfur compounds present in the fuel. He noted that SO2 emissions are

not a concern with natural gas-fired turbines. However, SO2 is emitted at higher levels by oil-

fired turbines because of the higher sulfur content of oil. IEPA Grp. Exh. 1, Romaine at 11.

b. Information from Industry. Maintaining that air emissions from peaker plants will

be very low, Mr. Erjavec of Indeck compared a proposed peaker plant’s air emissions with the

emissions of a number of different types of sources and the NAAQS. Tr.1 at 246-247; Indeck

Exh. 2, Average Permitted CO Emissions. He noted that the peaker plant’s emissions would

be in the mid-range when compared to other sources, such as steelworks, refineries, foundries,

coal-fired power plants, and airports. Tr.1 at 248. The comparison also illustrated that the

peaker plant’s emission levels would be significantly lower than the applicable NAAQS.

Indeck Exh. 2, Air Quality Impacts. According to Indeck, the emissions are low because:

peaker plants use clean burning natural gas; are equipped with low NOx burners; and are

designed to operate only during peak-load demand. Indeck Exh. 2, Representative Impact

Documentation.

12

3. Quantity of Air Emissions

a. Information from Government. Information on rates and amounts of pollutants that

peaker plants emit into the air focused mainly on NOx because peaker plants emit large

quantities of NOx and NOx is an ozone precursor. Tr.1 at 85; IEPA Grp. Exh. 2, No. 4 at 4-6.

The amount of NOx emitted from a particular gas turbine model depends on design factors, fuel

type, operating mode, and ambient conditions. IEPA Grp. Exh. 2, No. 4 at 4-6. Mr.

Romaine testified that “the preferred source of information [on] the expected emissions of a

particular model of turbine is the manufacturer of the turbine.” Tr.1 at 85.

Mr. Romaine stated that turbine manufacturers provide data sheets that include

maximum expected emissions under different operating, load, and ambient conditions. IEPA

Grp. Exh. 1, Romaine at 11. Manufacturers provide the amount of uncontrolled air emissions

from peaker plants in parts per million by volume (ppmv), which is converted to pounds per

hour based on turbine power output, heat rate, and fuel properties. IEPA Grp. Exh. 2, No. 4

at A-1. Versar stated that by knowing the number of hours per year the plant operates, the

amount of air emissions for a particular pollutant may be calculated on a tons per year (TPY)

basis. DuPage County Board Exh. 1 at 14-15.

USEPA has published the uncontrolled NOx emission factors based on manufacturers’

data for a number of gas turbine models. IEPA Grp. Exh. 2, No. 4 at 2-2. These emission

factors range from 0.397 to 1.72 lbs NOx/mmBtu (million British thermal unit) (99 to 430

ppmv) for natural gas and from 0.551 to 2.50 lbs NOx/mmBtu (150 to 680 ppmv)for distillate

oil fuels. Mr. Romaine stated that actual emission rates may be determined by measuring the

amount of pollutants in the turbine exhaust as it passes through the stack. Tr.1 at 85.

b. Information from Industry. Mr. Erjavec of Indeck presented air permitting

information on total emissions for a proposed 300-MW peaker plant in Libertyville. The

plant’s two turbines, when operated according to permit limits over a period of 2,000 hours,

would emit 173 tons of NOx, 105.4 tons of CO, 20 tons of PM, and 1 ton of SO2. Indeck

Exh.1, Att.

4. Start-Up, Shut-Down, and Low Load Emissions

a. Information from Citizens. Citizens were concerned about peaker plants emitting

greater amounts of pollutants when starting up, shutting down, and operating at low load.

Tr.1 at 789, 995, 998, 1,024; Tr.2 at 139, 148. Dr. William McCarthy, a resident of

Libertyville, stated that emissions during peaker plant start-up and shut-down would account

for a large part of the total emissions from peaker plants. Tr.1 at 995. He said that peaker

plants produce up to 200 parts per million (ppm) of NOx during start-up (when plants operate

at less than 50% load capacity), compared to NOx emissions of 10 to 30 ppm during full-load

operation. Tr.1 at 999-1,000. Ms. Dorge of LCCA also noted that peaker plant emissions are

13

much higher during start-up, particularly emissions of CO and VOM. Tr.1 at 451; Tr.2 at

149.

Dr. McCarthy stated that Illinois regulations do not specifically address emissions

during start-up and shut-down of peaker plants. Tr.1 at 998. He noted that because peaker

plants do not have any restrictions on how many times they can start up or shut down, a plant

may turn on and off many times on a given day based on market conditions, producing large

quantities of emissions. Tr.1 at 1,000-1,001.

Dr. McCarthy submitted a California Air Resources Board publication entitled

Guidance for Power Plant Siting and Best Available Control Technology, which recommends

that start-up and shut-down emissions be regulated by a separate set of limits to optimize

emission control. Tr.1 at 999; McCarthy Exh. 2 at 36-37. The guidance document is intended

to assist the various air districts within that state in making permitting decisions. McCarthy

Exh. 2 at 3. The guidance document notes that natural gas-fired power plants operate with

varying loads and have numerous start-ups and shut-downs, which can contribute substantially

to total annual emissions. It recommends that enforceable permit emission limits be set for

turbine emissions at all potential loads. The guidance document also states that permit

conditions must address limits on the number of daily and annual start-ups and shut-downs, as

well as monitoring the duration and quantity of start-up and shut-down emissions. McCarthy

Exh. 2 at 60.

Ms. Dorge of LCCA urged that the Board adopt regulations requiring turbine

manufacturers to provide information on start-up and shut-down emissions, alleging that the

manufacturers are reluctant or unwilling to provide the information. Tr.1 at 452, 455.

b. Information from Government. IEPA stated that gas turbines emit greater amounts

of pollutants during start-up and shut-down, including NOx, CO, and VOM. This occurs

because combustion efficiency will be at its lowest when fuel is first ignited and emission

control techniques are not effective until flows and temperature in the turbine exhaust reach

certain minimum levels. PC 9 at 13. IEPA acknowledged that emissions during start-up and

shut-down are higher when expressed as an emission factor (pounds of pollutant per mmBtu

heat input). However, IEPA noted that actual emissions may not be higher when expressed in

pounds per hour because the lower heat input during start-up and shut-down compensates for

the higher emission factor. PC 9 at 14.

IEPA relied on actual air quality monitoring information from the Elwood Energy

facility to illustrate that NOx emissions during an hour with start-up are similar or slightly

higher than those during an hour of normal operation. PC 168 at 9. IEPA stated:

The CEMS [continuous emissions monitoring system] data shows that the

peaking turbines presently at Elwood Energy normally operate at about 0.05 to

0.055 lb NOx/mmBtu. (The permit limit is 0.061 lb/mmBtu, based on an

14

exhaust concentration of 15 ppm NOx.) During startup, NOx emissions are in

the range of 0.1 to 0.115 lb/mmBtu. Of course, the average firing rate during a

startup is about half of the turbines’ capacity. This indicates that startup of

these peaking turbines does not significantly change the hourly NOx emissions of

these turbines. PC 168 at 10.

IEPA cautioned that a different conclusion would be reached with new turbines being added to

the Elwood Energy facility—because the new units are required to comply with a lower

emission rate during normal operation. IEPA noted that if the start-up emission rate remained

the same as with the existing turbines, the emissions during an hour with start-up could be

about 25% higher than those during a normal hour of operation. PC 168 at 10.

IEPA asserted that higher levels of emissions accompanying start-up and shut-down

occur over a relatively short period (15 to 30 minutes) and do not appear to pose an

extraordinary concern for air quality. IEPA stated that start-up and shut-down emissions are

another example of how emissions from particular units can vary, which must be addressed

during permitting. PC 9 at 14. IEPA noted that it requires peaker plant permit applicants to

account for all emissions (including emissions during start-up and shut- down) when

demonstrating compliance with annual emission limits. PC 9 at 15. IEPA acknowledged that

construction permits generally do not have specific emission limits for start-up and shut-down.

However, IEPA contended that specific limits are necessary only when elevated emissions

during those periods would threaten air quality. IEPA also noted that permit provisions

require that peaker plants implement measures to minimize emissions associated with start-up

and shut-down. PC 9 at 15.

IEPA explained that separate short-term permit limits are set if needed to protect

ambient air quality during low-load operation. PC 9 at 16. IEPA relies on the results of air

quality modeling to determine whether any particular turbine operation, such as low-load

operation, would threaten air quality. PC 9 at 28.

C. Air Pollution Control Regulations

1. Information from Citizens

Citizens expressed concern about the adequacy of existing air pollution control

regulations to address peaker plant emissions. They believe that peaker plants need to be

regulated more strictly than other sources of air pollution. Tr.1 at 450, 514, 782. They

addressed a number of specific issues concerning air pollution control regulations, including

regulating peaker plants as major sources, the New Source Performance Standard (NSPS) for

NOx, the NOx waiver, start-up and shut-down emissions, and permitting. This information is

summarized below.

15

a. Regulating Peaker Plants as Major Sources of Air Pollution. Individual citizens and

citizen groups argued that peaker plants, which are generally being permitted as minor sources

of air pollution, should be regulated as major sources of air pollution. Tr.1 at 453, 466, 514,

787. Ms. Zingle of LCCA testified that peaker plants restrict their hours of operation or fuel

consumption to limit NOx emissions below 250 TPY, thereby avoiding major source status.

Tr.1 at 514. As minor sources, she contended, peaker plants escape all but minimal air

regulations. Ms. Zingle maintained that limiting emissions to stay below the 250 TPY

threshold in no way limits the operating capacity of peaker plants because their emissions come

in just three summer months. Tr.1 at 512-516.

Ms. Dorge of LCCA also maintained that peaker plants should be regulated as major

sources of air pollution because they operate as major sources during the ozone season. Tr.1

at 453. Ms. Sandy Cole, the Lake County Board Commissioner for the 11th District, similarly

stated that peaker plants must be evaluated on the basis of daily emission rate. Tr.1 at 787;

Lake County Exh. 2 at 1. She asserted that because peaker plants operate only during times of

need, their annual emissions generally fall within the minor source category, making it easy for

companies to obtain permits. Tr.1 at 788.

b. NSPS for NOx. A number of citizens noted that the existing NSPS for NOx has

become obsolete. Tr.1 at 454, 1,006. Dr. McCarthy stated that the existing NOx NSPS of 75

ppm, which was adopted 13 years ago, has become outdated. Tr.1 at 1,006. Ms. Dorge stated

that peaker plants equipped with dry-low NOx combustion routinely achieve 9 ppm under

normal operations. Tr.1 at 454.

c. NOx Waiver. A number of citizens and citizen groups expressed concern regarding

the NOx waiver that USEPA granted to the State of Illinois for the Lake Michigan NAA. Tr.1

at 683; Tr.2 at 106, 116. Mr. Keith Harley of the Chicago Legal Clinic testified on behalf of

ten environmental and citizen groups concerning the NOx waiver. He stated that generally a

new source of NOx in a NAA for ozone, such as the Chicago metropolitan area, would be

regarded as a major source if the source had the potential to emit 25 TPY of NOx. Tr.1 at

683-684. Mr. Harley noted that under the federal Clean Air Act’s (CAA) New Source Review

(NSR) regulations, this major source would be subject to the most stringent pollution control

measure called the Lowest Achievable Emission rate (LAER) and would be required to acquire

NOx offsets in the ratio of 1.3 to 1. Tr.1 at 684.

However, Mr. Harley noted that in mid-1990s the State of Illinois obtained a NOx

waiver from USEPA that relieved the sources in the Chicago NAA from NSR requirements,

including the major source designation threshold of 25 TPY of NOx. Tr.1 at 684. He stated

that the NOx waiver was granted on the basis of preliminary information suggesting that

reducing NOx emissions in the NAA would not reduce ozone levels in the NAA. Tr.1 at 685.

Mr. Harley asserted that because of the NOx waiver a peaker plant is not considered a major

16

source unless it emits 250 tons of NOx per year. He noted that it is not a coincidence that all

peaker plants are being permitted below the 250 TPY threshold. Tr.1 at 685-686.

Mr. Harley stated that since the granting of the NOx waiver, the basis for the waiver

has been discredited by the USEPA-appointed Ozone Transport Assessment Group (OTAG).

Tr.1 at 686. He noted that the OTAG’s comprehensive study demonstrated that NOx

reductions locally and regionally reduce ozone levels in the NAA. Mr. Harley stated that

USEPA responded to the OTAG findings by imposing statewide NOx reductions in a number

of states, including Illinois,

i.e.

, the NOx State Implementation Plan (SIP) call. However, no

action has been taken to reconsider the Illinois NOx waiver. Tr.1 at 686.

Mr. Harley asserted that the NOx waiver provides a loophole for peaker plants to be

built in the Chicago NAA. He maintained that Illinois could voluntarily request USEPA to

rescind the NOx waiver. Tr.1 at 687. Mr. Harley noted that he has filed a petition with

USEPA requesting the federal agency to rescind the NOx waiver for the Chicago NAA. Tr.1

at 688. Mr. Harley’s position on the NOx waiver was echoed by Mr. Brian Urbaszewski, the

Director of Environmental Health Programs for the American Lung Association of

Metropolitan Chicago (ALAMC) and a board member of the Illinois Environmental Council

(IEC). Tr.2 at 107. Mr. Urbaszewski testified that Governor Ryan should request USEPA to

repeal the NOx waiver. Tr.2 at 116.

NRDC recommended that USEPA “withdraw the section 182(f) NOx waiver granted to

the Chicago . . . ozone [NAA], which exempts proposed new single cycle combustion turbines

from obtaining emission offsets or utilizing best available control technology [BACT].” PC

109 at 6.

d. Regulating Start-Up and Shut-Down Emissions. A number of citizens expressed

concern regarding the higher emission levels during start-up and shut-down of peaker plants.

Dr. McCarthy stated that Illinois does not regulate start-up and shut-downs of peaker plants.

Tr.1 at 998. He noted that peaker plants do not have any restrictions on how many times they

can start and shut down. Accordingly, on any given day, based on market conditions, a plant

may turn on and turn off many times, producing large quantities of emissions. Tr.1 at 1,000-

1,001. Ms. Dorge asserted that some of the peaker plants that IEPA permitted as minor

sources (NOx emissions less than 250 TPY) would be major sources if start-up emissions were

included in the overall annual emissions. Tr.2 at 149.

17

e. Permitting Issues. Ms. Dorge testified that regulations should better define the

permit application requirements. Tr.1 at 458. She stated that every peaker plant permit

application should include information on duration and expected frequency of start-up and

shut-down emissions, good operating practices, operating factors affecting emission rates,

standard procedures for calculating emission rates during all operational modes, monitoring

procedures, operator information, operator training, and contractual warranties. Tr.1 at 455-

457.

Further, Ms. Dorge stated that it is important to know what constitutes a complete

permit application. Using a permit application that Carlton, Inc. filed as an example, Ms.

Dorge identified what she considers to be a number of inconsistencies and deficiencies in the

information that the applicant provided. Tr.2 at 144-147.

Ms. Turnball expressed concern regarding public access to permit information. Tr.1 at

441. She suggested that the permit applicant should be required to provide public notice

concerning the proposed plant to all property owners within 500 feet of the proposed facility.

Ms. Turnball also stated that all information that an applicant provides in an air permit

application should be verified by actual operating data. Tr.1 at 438. Dr. McCarthy noted that

there is no need to have any operating data to obtain a construction permit in Illinois. Tr.1 at

1,007. In addition, Ms. Turnball urged the Board to make permanent the requirement for a

public hearing on construction permits for peaker plants that is currently being imposed at the

discretion of IEPA Director Skinner. Tr.1 at 513.

f. NOx SIP Call. Ms. Dorge stated that the 40 or so proposed peaker plants would

account for approximately 10,000 tons of NOx per year compared to roughly 30,000 tons

allocated to Illinois under the proposed NOx trading program. Tr.1 at 450. She noted that this

comparison clearly shows that peaker plant contribution to the ozone problem will be

significant. Tr.1 at 450. Ms. Zingle also expressed concern regarding the implications of

siting a large number of peaker plants on existing NOx emitters in the context of the NOx SIP

call. Tr.1 at 660.

Mr. Larry Eaton is an attorney formerly with the Illinois Attorney General’s office in

environmental enforcement. Mr. Eaton testified on behalf of three organizations associated

with the conservation community known as Prairie Crossing: Prairie Crossing Homeowners

Association; Liberty Prairie Conservancy, a foundation dedicated to preserving Prairie

Crossing and other communities; and Prairie Holdings Corporation, the developer of Prairie

Crossing. Tr.1 at 864, 905; Eaton Exh. 1 at 1. Mr. Eaton stated that the NOx SIP call

requires Illinois to quickly and radically reduce NOx emissions. Tr.1 at 882. He asserted that

the SIP call demonstrates the need for better planning and regulations for power plant industry.

Tr.1 at 883.

Mr. Patricio Silva, Midwest Activities Coordinator of NRDC, stated that, while the

NOx SIP call is a tool to achieve the one-hour ozone standard, it will have a technology forcing

18

edge. Tr.2 at 90. However, Mr. Silva asserted that the NOx waiver will negate the use of

innovative technology. He argued that the allocation methodology under the proposed SIP call

regulations favor the existing sources at the expense of future sources with cutting-edge

technology. Tr.2 at 91.

Mr. Urbaszewski of ALAMC and IEC echoed Mr. Silva’s concern regarding the

allocation methodology under the proposed NOx SIP call rules. Tr.2 at 111. Further, he

asserted that the NOx allocation methodology does not support energy efficiency and renewable

energy projects. Tr.2 at 112. Mr. Urbaszewski did not agree that the NOx SIP call would

address all the concerns related to NOx emissions from peaker plants. Mr. Urbaszewski stated

that the new units may have to import allocations from other states in the trading region

because a very small portion of the NOx budget is set aside for these new sources under the

proposed allocation methodology. Tr.2 at 122. He argued that the amount of allowances

imported would go down if peaker plants are required to emit NOx at low levels. Tr.2 at 122.

2. Information from Government

Mr. Romaine of IEPA testified about the air pollution control regulations governing the

peaker plants. Tr.1 89-93; IEPA Grp. Exh. 1, Romaine, Att. 1. He explained the

applicability of the federal regulations:

If emissions from a proposed new source of air pollution or from a modification

to an existing source are considered major, the source must undergo federal . . .

NSR . . . analysis as part of the construction permitting process. Different NSR

rules govern areas that attain the . . . NAAQS . . . for pollutants and in areas

that do not attain the NAAQS. These national standards are established by

[USEPA] under Section 109 of the [CAA] (42 U.S.C. Section 7401-7661q

(CAA) and are set at a level that protects the public health with an adequate

margin of safety and protects public welfare from known or anticipated adverse

effects. Peaker plants emit the following pollutants for which [USEPA] has

established national standards: . . . NO2 . . . , . . . PM . . . SO2 . . . CO . . . .

In addition, . . . VOM . . . and sometimes . . . NOx . . . emissions, both of

which are emitted by peaker plants are subject to regulation as precursors to

ozone. Attainment NSR is addressed under the Prevention of Significant

Deterioration (PSD) program found at 40 C.F.R. Section 52.21. IEPA Grp.

Exh. 1, Romaine, Att. 1 at 1.

Further, Mr. Romaine explained that if “an area does not attain the NAAQS, it is

considered a [NAA] and proposed new or modified major sources are subject to nonattainment

NSR . . . . Illinois’ [nonattainment] NSR requirements are found at 35 Ill. Adm. Code 203.”

IEPA Grp. Exh. 1, Romaine, Att. 1 at 2.

19

a. Prevention of Significant Deterioration (PSD) of Air Quality.

Versar,

environmental consultant for the DuPage County Department of Development and

Environmental Concerns, also discussed the air pollution control regulations. DuPage County

Board Exh. 1 at 27. Versar stated that the PSD program is designed “to ensure that the

current NAAQS levels are not degraded such that exceedences of the standard would occur.”

DuPage County Board Exh. 1 at 28. Mr. Romaine stated that IEPA implements the federal

PSD regulations under a delegation agreement with USEPA. IEPA Grp. Exh. 1, Romaine at

13. Mr. Romaine explained the applicability of PSD to peaker plants:

Under PSD, a new source or a modification to an existing minor source is

considered major if potential emissions of a pollutant are 250 [TPY] or more

unless the source is one of the listed categories at 40 CFR Section

52.21(b)(1)(i)(a). If a source is one of the listed categories, it is considered

major if its potential emissions of a pollutant are 100 [TPY] or more.

Id.

This

list includes fossil fuel steam electric plants of more than 250 [mmBtu] per hour

of heat input. Peaker plants that use simple cycle gas-fired turbines are not

covered by this category or any other listed categories, as the turbines used in

peaker plants do not generate steam. Therefore, the PSD threshold for simple

cycle peaker plants is 250 [TPY]. If the gas-fired turbine produces electricity

by steam through a waste recovery system, often referred to as combined cycle

turbines, the plant would be reviewed under the 100 [TPY] or more threshold.

Once a proposed source qualifies as major for one pollutant, other pollutants

only need be emitted in a significant amount, as defined at 40 CFR Section

52.21(b)(23) to be subject to PSD. IEPA Grp. Exh. 1, Romaine, Att. 1 at 1-2.

Mr. Romaine stated that PSD can have an effect on peaker plants because a plant that

qualifies as major for a pollutant is subject to additional requirements for that pollutant. He

noted that a major plant must be operated to comply with control requirements that represent

BACT for the pollutant, as determined and approved on a case-by-case basis during issuance of

the construction permit for the project. IEPA Grp. Exh. 1, Romaine at 13. In addition, Mr.

Romaine explained that a permit applicant for a major source or modification “must perform

modeling to determine the air quality impact of its proposed project, using dispersion modeling

for pollutants other than ozone.” IEPA Grp. Exh. 1, Romaine, Att. 1 at 2. He added:

To address the air quality impacts from individual sources of ozone precursors,

[USEPA] has developed screening tables based on generic airshed ozone

modeling. Dispersion modeling is not relied upon under PSD to address the air

quality impact from ozone precursor emissions because ambient ozone is formed

by atmospheric reactions of precursor compounds and the impact of a single

source cannot typically be measured through modeling. IEPA Grp. Exh. 1,

Romaine, Att. 1 at 2.

20

Mr. Romaine discussed the applicability of PSD to peaker plants to address public

concern over why all peaker plants are not considered major sources. He stated that the need

for a PSD permit is triggered for a new peaker plant if the permitted emissions of a pollutant

(NOx, SO2, CO, PM, or VOM) that the applicant requests equal or exceed the major source

threshold for PSD. IEPA Grp. Exh. 1, Romaine at 14. Mr. Romaine noted that the major

source threshold for PSD is set at annual emissions of 100 tons or more for 28 listed

categories, and 250 tons for all other categories of sources. IEPA Grp. Exh. 1, Romaine at

15. Further, regarding the issue of why the PSD program is not applied on the basis of

seasonal emissions,

i.e.

, summer months, Mr. Romaine maintained that the applicability

provisions of the PSD rules do not provide a basis to trigger applicability of PSD on any

emission totals other than annual emissions. He noted that Section 169 of the federal CAA

clearly provides that for purposes of PSD, major sources are to be defined in terms of their

annual emissions. Mr. Romaine stated that peaker plants are not the only plants that are

seasonal in nature. He noted that some boilers at heating plants operate primarily in winter.

IEPA Grp. Exh. 1, Romaine at 15-16.

Mr. Romaine also addressed the issue of why IEPA was considering PSD for NOx in

the Chicago NAA. He stated that if NOx was considered an ozone precursor in the NAA, a

proposed peaker plant would have to comply with the Major Stationary Sources Construction

and Modification (MSSCAM) regulations. The applicability threshold for MSSCAM is annual

emissions of 25 tons of an ozone precursor. IEPA Grp. Exh. 1, Romaine at 16. However,

Mr. Romaine stated:

[USEPA] has granted the states bordering Lake Michigan a NOx waiver under

Section 182(f) of the [CAA]. This waiver is based on scientific analyses that

found that controlling NOx emissions only in the [NAA] would actually increase

ozone levels in the area. Instead, for NOx reductions to improve ozone air

quality, they must be provided on a statewide basis and preferably on a multi-

state regional basis. IEPA Grp. Exh. 1, Romaine at 16.

Mr. Romaine stated that because of the public concerns regarding the applicability of

PSD to peaker plants, IEPA formally sought guidance from USEPA on implementing PSD.

He noted that USEPA confirmed that IEPA is properly implementing the applicability

provisions of the PSD rules for these plants. IEPA Grp. Exh. 1, Romaine at 17.

b. Nonattainment NSR.

Mr Romaine stated that in an area that is designated as

nonattainment for a pollutant, PSD does not apply to a proposed project for emissions of the

nonattainment pollutant or, in the case of ozone nonattainment, the ozone precursors. He

stated that a separate state permit program called MSSCAM or nonattainment NSR (35 Ill.

Adm. Code 203) addresses emissions of nonattainment pollutants from a proposed source in

the area. IEPA Grp. Exh. 1, Romaine at 14. A proposed project that qualifies as major under

the applicability thresholds of MSSCAM must control emissions of the nonattainment pollutant

to the LAER, rather than BACT. The project must also provide “offsets” for its emissions.

21

Mr. Romaine explained that “[o]ffsets are emission reductions that have not been relied upon

to demonstrate attainment [and] that have or will occur from existing sources already in the

[NAA].” IEPA Grp. Exh. 1, Romaine at 14, n. 4.

Mr. Romaine explained that in the Chicago area, which is designated as severe

nonattainment for ozone, a source may be considered major if it has potential to emit 25 tons

or more of VOM per year. IEPA Grp. Exh. 2, Romaine, Att. 1 at 2. He noted that NOx

emissions are sometimes regulated as an ozone precursor. However, in the Chicago NAA,

NOx is reviewed under PSD because USEPA has granted a NOx waiver. (Issues concerning

the NOx waiver are discussed further below.) In the Metro-East/St.Louis area, which is

designated as moderate NAA for ozone, Mr. Romaine noted that a source is considered as

major if it has potential to emit 100 tons of VOM or NOx. IEPA Grp. Exh. 2, Romaine, Att. 1

at 2. Further, Mr. Romaine noted that like the PSD program, the applicability of

nonattainment NSR is determined on the basis of potential annual emissions, even if a relevant

air pollution problem is seasonal in nature, such as ozone pollution that only occurs during

summer months. IEPA Grp. Exh. 2, Romaine, Att. 1 at 4.

c. NOx Waiver. Ms. Kathleen Bassi, Assistant for Program and Policy Coordination

for IEPA’s Bureau of Air, responded to citizen concerns regarding the NOx waiver that

USEPA granted for the Chicago NAA. In responding to the citizens’ position that the waiver

should be revoked, Ms. Bassi stated that the removal of the NOx waiver would have

ramifications well beyond the scope of the inquiry proceedings. Tr.2 at 204-205. She noted

that NOx waiver affects all NOx source in the Chicago NAA and not just peaker plants. In

light of this, Ms. Bassi asserted that any decisions on the NOx waiver should be made by

USEPA in the context of its review of the attainment demonstration for the Chicago NAA.

Tr.2 at 206. She noted that USEPA would be performing its review of the State’s attainment

demonstration in the very near future. Tr.2 at 207. Ms. Bassi also clarified that the NOx

waiver does not limit the scope of control measures or reductions that may be required of

power plants.

d. NSPS.

Mr. Romaine stated that USEPA promulgated NSPS for emissions from

new turbines under Section 111 of the CAA, found at 40 C.F.R. 60, Subpart GG. IEPA Grp.

Exh. 2, Romaine, Att. 1 at 5. He noted that IEPA implements the federal NSPS in Illinois

pursuant a delegation agreement with USEPA. Mr. Romaine explained the applicability of

NSPS to gas turbines:

These standards apply to stationary gas turbines with a heat input at peak load

equal to or greater than 10.7 gigajoules per hour that commence construction,

modification, or reconstruction after October 3, 1977. The limit for NOx

emissions from large turbines, such as those used in peaking power plants, is

approximately 75 [ppm]. The exact limit varies by model of turbine because the

limit is adjusted for the efficiency of the turbine. Additionally, such turbines

may not use any gas that contains [SO2] in excess of 0.015 percent by volume at

22

15 percent oxygen on a dry basis and sulfur in excess of 0.8 percent by weight.

IEPA Grp. Exh. 2, Romaine, Att. 1 at 5.

Versar noted that NSPS also contain monitoring, testing, reporting, and record keeping

requirements that the operator of a peaker plant must follow to prove the standards are being

attained and the equipment is properly maintained. DuPage County. Bd. Exh. 1 at 28.

Mr. Romaine agreed with the citizens that the NSPS no longer reflects the Best

Available Control Technology (BACT) for new equipment. IEPA Grp. Exh. 2, Romaine, Att.

1 at 5. He noted that new natural gas-fired turbines are routinely designed to achieve 25 ppm

of NOx and low sulfur oil that meets the sulfur content limitations is readily available.

e. Hazardous Air Pollutants. Mr. Romaine stated that if a new or reconstructed peaker

plant is considered major for emissions of hazardous air pollutants (HAPs), it must undergo

review under Section 112(g) of the CAA, which is implemented in Illinois under Section

39.5(19)(e) of the Environmental Protection Act (Act) (415 ILCS 5/39.5(19)(e) (1998)). He

noted that a source is considered major for HAPs if it emits 10 TPY or more of any individual

HAP or 25 TPY or more of all HAPs aggregated. IEPA Grp. Exh. 1, Romaine, Att. 1 at 5.

Mr. Romaine explained that a new major source of HAP emissions must achieve the

maximum degree of reduction that is deemed achievable for new sources in a category or

subcategory and may not be less stringent than the emission control achieved in practice by the

best controlled similar source, often referred to as the Maximum Achievable Control

Technology (MACT). IEPA Grp. Exh. 1, Romaine, Att. 1 at 5. He stated that MACT is

implemented on a case-by-case basis during construction permitting until a National Emission

Standard for Hazardous Air Pollutant (NESHAP) is promulgated for the relevant source

category. Mr. Romaine noted that USEPA intends to develop a NESHAP to address HAPs

that stationary combustion turbines emit. IEPA Grp. Exh. 1, Romaine, Att. 1 at 7. He said

that USEPA expects to propose this NESHAP, which is likely to address peaker plants, before

the end of the year and finalize a standard in 2002. 65 Fed. Reg. 21,363 (April 21, 2000).

Mr. Romaine stated that peaker plants generally are not known to emit more than

de

minimis

levels of HAPs. He did note that natural gas-fired combustion units emit

formaldehyde, which is listed under Section 112(b)(l) of the CAA. However, emission levels

from peaker plants in Illinois have not been great enough to trigger new source analysis under

Section 112(g) of the CAA. IEPA Grp. Exh. 1, Romaine, Att. 1 at 5.

f. Title IV Acid Rain Requirements. Mr. Romaine stated that new peaker plants are

considered affected sources for acid rain deposition under 42 U.S.C. § 7642(e). He noted that

existing units that were operational before the 1990 amendments to the CAA may be entitled to

an allocation of SO2 allowances. However, new sources are required to obtain allowances after

January 1, 2000. IEPA Grp. Exh. 1, Romaine, Att. 1 at 5. Some existing peaker plants in

Illinois are not considered affected sources for acid rain deposition because they do not serve

23

generators with a nameplate capacity of more than 25 MW (42 U.S.C. § 7641(8)) and are,

therefore, not subject to requirements under Title IV. IEPA Grp. Exh. 1, Romaine, Att. 1 at

6. Mr. Romaine noted that peaker plants must also obtain an acid rain permit from IEPA

before starting to operate. These permits are issued in Illinois under the authority of the Clean

Air Act Permit Program (CAAPP) at 415 ILCS 5/39.5(17). IEPA Grp. Exh. 1, Romaine, Att.

1 at 6.

g. Operating Permit Requirements. Mr. Romaine stated that because peaker plants are

affected sources for acid rain deposition under Title IV of the CAA, they are required to obtain

a CAAPP operating permit pursuant to Section 39.5 of the Act. He explained that a peaker

plant operator must obtain an acid rain permit before operating. However, the operator must

apply for the very detailed CAAPP operating permit one year after starting to operate the

facility. IEPA Grp. Exh. 1, Romaine, Att. 1 at 6.

h. State Requirements. In addition to the federal regulations described above, Mr.

Romaine stated that peaker plants may be subject to certain State regulations.

i.

PM.

Mr. Romaine stated that the Board’s generic regulations that prohibit emissions

of visible PM emissions into the atmosphere apply to peaker plants. However, he noted that

natural gas-fired peaker plants do not generally emit significant amounts of PM emissions if

proper combustion occurs. IEPA Grp. Exh. 1, Romaine, Att. 1 at 6.

ii.

Emissions Reduction Market System (ERMS).

Mr. Romaine stated that if a peaker

plant located in the Chicago ozone NAA emits at least 10 tons of VOM during the ozone

season (May through September), the plant would be subject to the Emissions Reduction